World's Oldest Fossilized Mushroom Sprouted 115 Million Years Ago

About 115 million years ago, when car-size pterosaurs flew overhead and long-necked sauropods tromped about on Earth, a tiny mushroom no taller than a chess piece fell into a river and later fossilized — a feat that makes it the oldest-known fossilized mushroom on record, a new study finds.

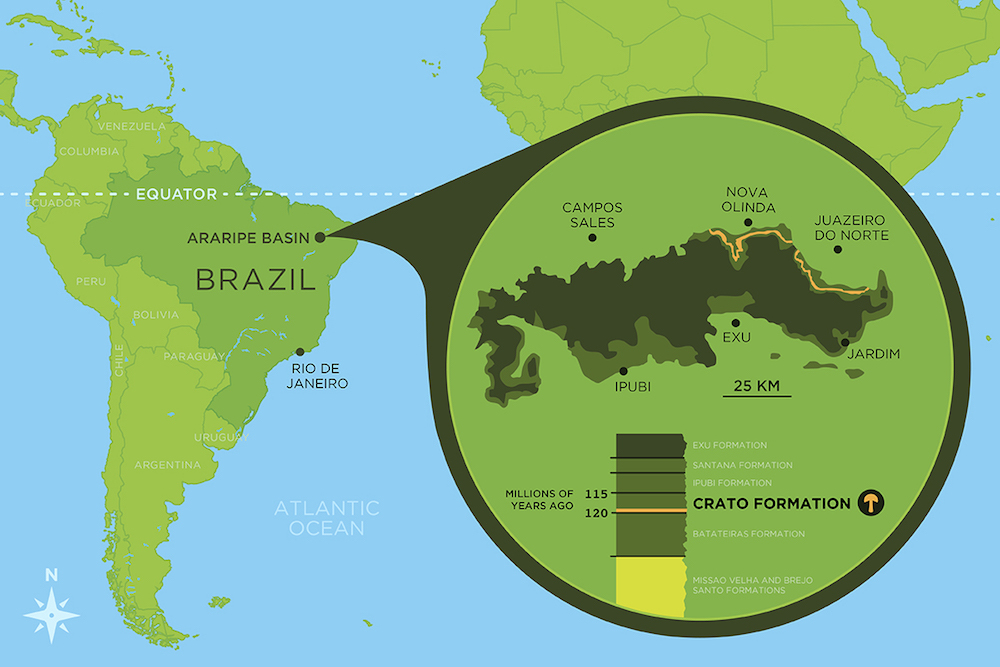

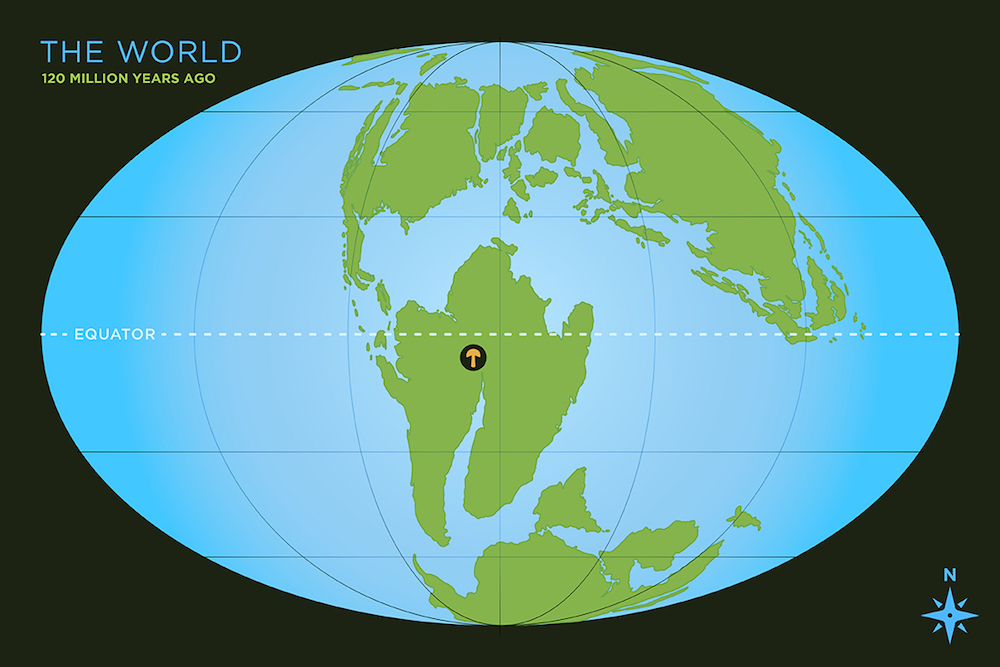

Researchers discovered the remains of the Cretaceous-age mushroom preserved in limestone from northeast Brazil's Crato Formation. But during its brief life, the mushroom lived on Gondwana, a supercontinent that once existed in the Southern Hemisphere.

"Most mushrooms grow and are gone within a few days," study lead researcher Sam Heads, a paleontologist at Illinois Natural History Survey (INHS), said in a statement. "The fact that this mushroom was preserved at all is just astonishing." [6 Ways Fungi Can Help Humanity]

After the mushroom fell into the river, it floated into a salty lagoon and sank to the bottom, where fine sediments began to cover it. Over time, the mushroom mineralized, and its tissues were replaced with pyrite, a mineral also known as fool's gold. Later, the pyrite transformed into the mineral goethite, the researchers said.

"When you think about it, the chances of this thing being here — the hurdles it had to overcome to get from where it was growing into the lagoon, be mineralized and preserved for 115 million years — have to be minuscule," said Heads, who found the mushroom while digitizing a collection of fossils from the Crato Formation.

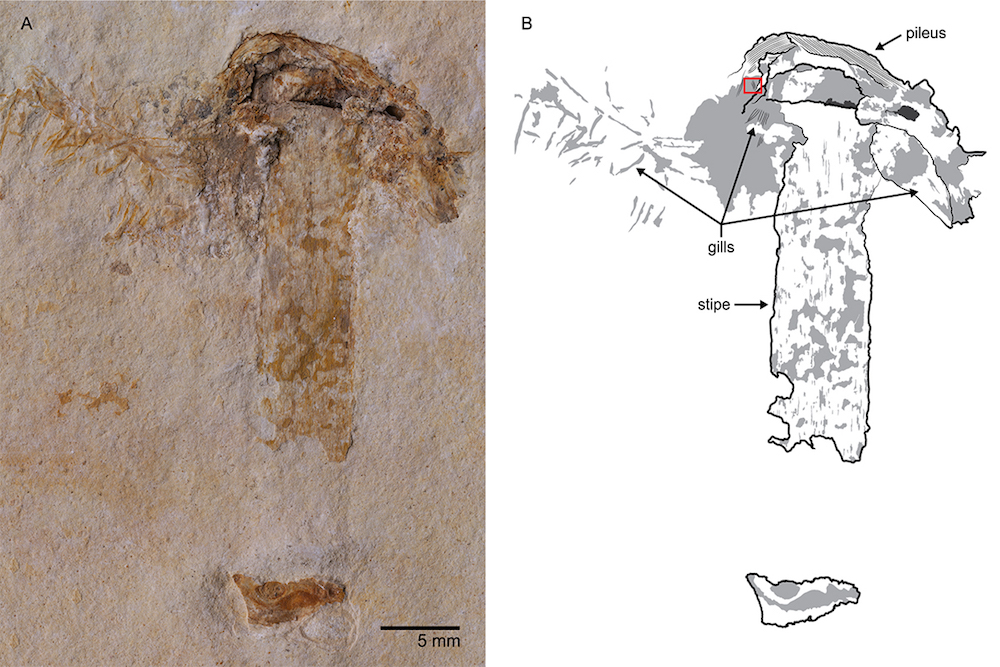

Researchers named the 2-inch-tall (5 centimeters) mushroom Gondwanagaricites magnificus. The genus name combines Gondwana with "agarikon," the Greek word for mushroom. The species name is Latin for "magnificent," because the specimen had remarkable preservation, the researchers said.

An electron microscope image revealed the mushroom had gills under its cap, instead of pores or spines (also called teeth). These gills, which release spores, helped the researchers place the mushroom in a scientific order of gilled mushrooms called Agaricales, they said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Until now, the oldest fungi on record were 99-million-year-old specimens (Palaeoagaricites antiquus) trapped in amber from Burma (also known as Myanmar), said study co-author Andrew Miller, an INHS mycologist (someone who studies fungi).

"They were enveloped by a sticky tree resin and preserved as the resin fossilized, forming amber," Heads said. "This is a much more likely scenario for the preservation of a mushroom, since resin falling from a tree directly onto the forest floor could readily preserve specimens. This certainly seems to have been the case, given the mushroom fossil record to date."

In fact, there are only 10 fossils resembling modern-day gilled mushrooms on record, and all of them are preserved in amber, the researchers said. These include four unnamed mushrooms from Burmese amber, a 94-million-year-old mushroom (Archaeomarasmius leggetti) from New Jersey, a 45-million-year-old mushroom (Gerontomyces lepidotus) from the Samland Peninsula of Russia, three mushrooms (Aureofungus yaniguaensis, Coprinites dominicana and Protomycena electra) from the Dominican Republic that date to between 16 million and 18 million years ago, and the Myanmar mushroom.

In all, the newfound G. magnificus isn't just the oldest fossil of a mushroom on record — it's also the oldest-known gilled mushroom, the only fossil mushroom known from a mineralized replacement and the first mushroom fossil from Gondwana, the researchers wrote in the study. [Images: Amazing Dominican Amber Trove]

"Fungi evolved before land plants and are responsible for the transition of plants from an aquatic to a terrestrial environment," Miller said. "Associations formed between the fungal hyphae [tubes] and plant roots. The fungi shuttled water and nutrients to the plants, which enabled land plants to adapt to a dry, nutrient-poor soil, and the plants fed sugars to the fungi through photosynthesis. This association still exists today."

The study was published online today (June 7) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.