5 Times 'Aliens' Fooled Us

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

D'Oh!

Astronomer Antonio Paris thinks a mysterious radio signal dubbed the Wow! signal — which many speculated was from extraterrestrials — was a passing comet emitting in a particular radio band. While few astronomers think the Wow! signal is E.T. phoning us, it's one of several natural or human-made radio transmissions that initially had scientists (and sometimes the public) thinking that we finally found evidence we aren't the only intelligent life in the universe.

A list of some of the more (in)famous examples shows that even though we haven't heard aliens yet, some have led to the most important finds in radio astronomy, deepening our understanding of the universe. It offsets the ones that left us with the immortal words of Homer Simpson: "D'Oh!"

Little green men

While working on a doctorate in astrophysics, Jocelyn Bell Burnell and her supervisor Antony Hewish heard a bright, repeating radio signal on Nov. 28, 1967. Even though they didn't immediately determine it was aliens, Bell, recounting the story in 1977, said she and Hewish noted the signal seemed too fast for any kind of star known then, and the timing seemed too precise. At first, they thought it was a signal from some human transmission on Earth, but the source moved across the sky with the stars, rather than moving quickly the way a satellite would.

Once the signal was picked up by other radio telescopes, it was clear that it was from outside the solar system, and within the galaxy. The team initially dubbed the radio source "LGM-1" for "little green men." They did not announce the finding of another civilization because they were cautious, and that turned out to be a good thing. [Why Do We Imagine Aliens as 'Little Green Men'?]

Burnell found another similar signal, in another part of the sky. Since it was unlikely that two different civilizations would choose the same frequency to broadcast on, the source was probably natural. It turned out to be a pulsar — short for "pulsating star" — and it confirmed a prediction made decades earlier by astronomers Fritz Zwicky and Walter Baade, who said that a sufficiently dense star made up of neutrons could form after a supernova. Rather than little green men, Bell and Hewish had found the corpse of a dead star, leading to an entire branch of astronomy that still yields new insights into how stars age and die.

HD 164595

HD 164595 is a star in the constellation Hercules, about 94 light-years from Earth — in our backyard on galactic scales. It's a lot like the sun and even hosts a planet, called HD 164595 b. The planet isn't a likely abode for life like our own, since it has a mass of some 16 times that of Earth and orbits its star closer than Mercury does the sun — its "year" takes just 40 days, according to the NASA exoplanet archive.

In 2016, news outlets (such as CNN) reported a burst of microwave radiation from the star picked up by a radio telescope in Russia might be evidence of an alien civilization.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, it was not to be.

To make a signal at that wavelength (11 gigahertz) powerful enough to be detected at such a distance and so "loud" would require huge amounts of energy; and if the signal were broadcast in all directions, it would require more energy than all the sunlight that reaches Earth, on the order of 100 billion billion watts, as noted by the Kurzweil Network's blog. The wavelength is a clue: The frequency used is the same as that of some military transmissions, so it might have been a stray transmission from a satellite, or a signal from Earth reflected in such a way as to appear to come from the sky. The signal was never heard again.

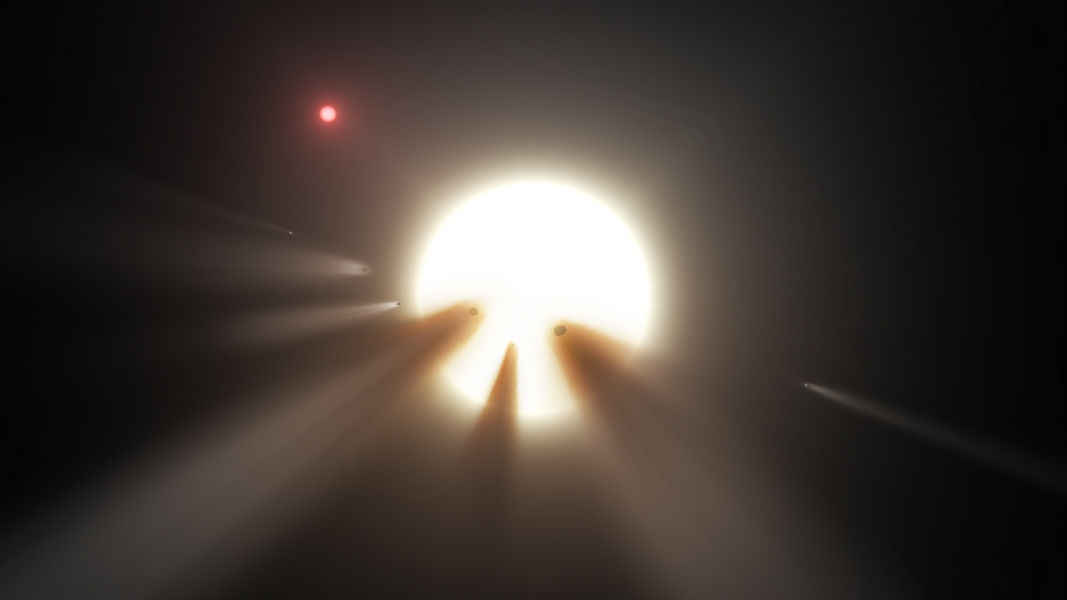

Alien megastructures?

In 2015, astronomer Tabetha Boyajian of Yale University and her colleagues found something odd about KIC 8462852 as they searched for planets with the Kepler Space Telescope. Planets have a characteristic "light curve" — as a planet transits in front of a star, the star's light gets fainter and then brightens again, and this happens at regular intervals. This star was dimming dramatically in just a short time, and flickering as well. Whatever it was, a planet couldn't explain it. At first, some thought it might be an alien megastructure — some kind of giant energy-harvesting project. Jason Wright, as astronomer at Penn State University, suggested the star might be surrounded by a swarm of giant satellites.

However, since then, while the star has acted odd once again, most astronomers now think it is a natural phenomenon — perhaps a swarm of comets, or a destroyed planet, or perhaps some odd magnetic effect. So far, no hypothesis has appeared a front-runner, but aliens do not seem to be among the contenders.

Fast radio bursts

In January 2017, Abraham Loeb and Manasvi Lingam submitted a paper to Astrophysical Journal Letters proposing that fast radio bursts (FRBs) might be alien starships. Fast radio bursts last only fractions of a second, and seem to originate outside our galaxy. Loeb and Manasvi calculated that an alien civilization might use such bursts to push a solar-sail type spacecraft weighing millions of tons.

Thus far, this doesn't seem to be the case. Recent work has shown that FRBs do repeat periodically and seem to be associated with black holes. The discovery, though, has opened up whole new avenues of research into black hole physics and the their behavior of matter as it falls in.

Perytons

For several years, the Parkes radio telescope in Australia and the Bleien Radio Observatory in Switzerland picked up signals called "perytons," which were transient (lasting just milliseconds), in a narrow frequency range (gigahertz), and seemed to resemble fast radio bursts. The similarity meant that even the origins of FRBs had to be called into question; these signals didn't look like ordinary interference, and they seemed to cluster at certain times of day.

Dr. Emily Petroff, then a doctoral student at Swinburne University in Australia, led a team that solved the mystery: microwave ovens. In her 2015 study, she noted the ovens were emitting a radio signal every time a user got impatient and opened it before it was completely done, and sometimes they'd emit "clusters" of perytons when one used a microwave at less than 100 percent power.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus