1,000-Year-Old Colored Glass Beads Discovered in West Africa

A newly discovered treasure trove of more than 10,000 colorful glass beads, as well as evidence of glassmaking tools, suggests that an ancient city in southwestern Nigeria was one of the first places in West Africa to master the complex art of glassmaking, scientists reported.

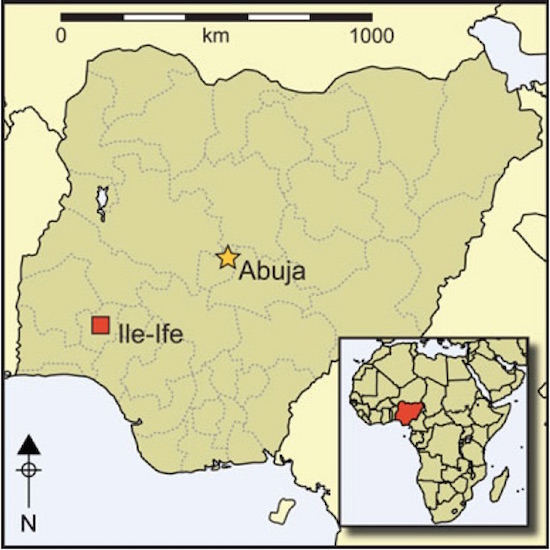

The finding shows that people who lived in the ancient city of Ile-Ife learned how to make their own glass using local materials and fashion it into colorful beads, said study lead researcher Abidemi Babalola, a fellow at Harvard University's Hutchins Center for African & African American Research.

"Now we know that, at least from the 11th to 15th centuries [A.D.], there was primary glass production in sub-Saharan Africa," said Babalola, who specializes in African archaeology. [The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

Ancient city of IIe-Ife

The ancient city of Ile-Ife was the ancestral home of the Yoruba, an ethnic group of people who live in Africa today. The Yoruba people view Ile-Ife as the mythic birthplace of several of their deities, Babalola and his colleagues wrote in the study.

Ile-Ife is also widely known for its copper alloy and terracotta heads and figurines that were made between the 12th and 15th centuries A.D., the researchers said.

Some of the figurines are decorated with glass beads on their headdresses, crowns, necklaces, armlets and anklets, the researchers said. Moreover, archaeologists have found glass beads at Ile-Ife's ancient shrines and within unearthed crucibles — ceramic containers that were used to melt glass.

Where did these glass beads come from? Most researchers speculated that the beads arrived from afar through trade, possibly from the Mediterranean area or the Middle East, and that artisans in Ile-Ife used crucibles to melt and refashion some of them into new beads, Babalola told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But Babalola and a handful of other researchers suspected that the answer was closer to home. To find out, Babalola traveled to Igbo-Olokun, an archaeological site within Ile-Ife, and excavated several places from 2011 to 2012, searching for evidence of local glass production, he said.

Crystal clear

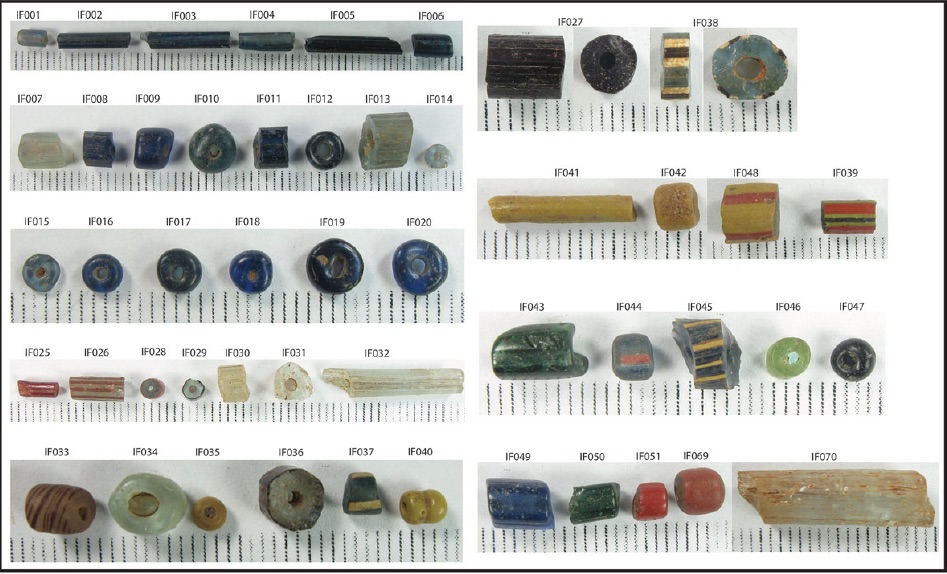

Babalola discovered a treasure trove during the excavation, finding almost 13,000 beads, 812 crucible fragments, 403 fragments of ceramic cylinders (rods that were possibly used to handle the crucible lids), almost 7 lbs. (3 kilograms) of glass waste and about 14,000 potsherds, the researchers wrote in the study.

Babalola didn't find any furnaces that would have helped artisans heat the crucibles, but "the abundance of glass-production debris and the presence of vitrified clay fragments [clay with melted glass on it] indicate, however, that these areas were in, or very near, a zone of glass workshops," the researchers wrote in the study.

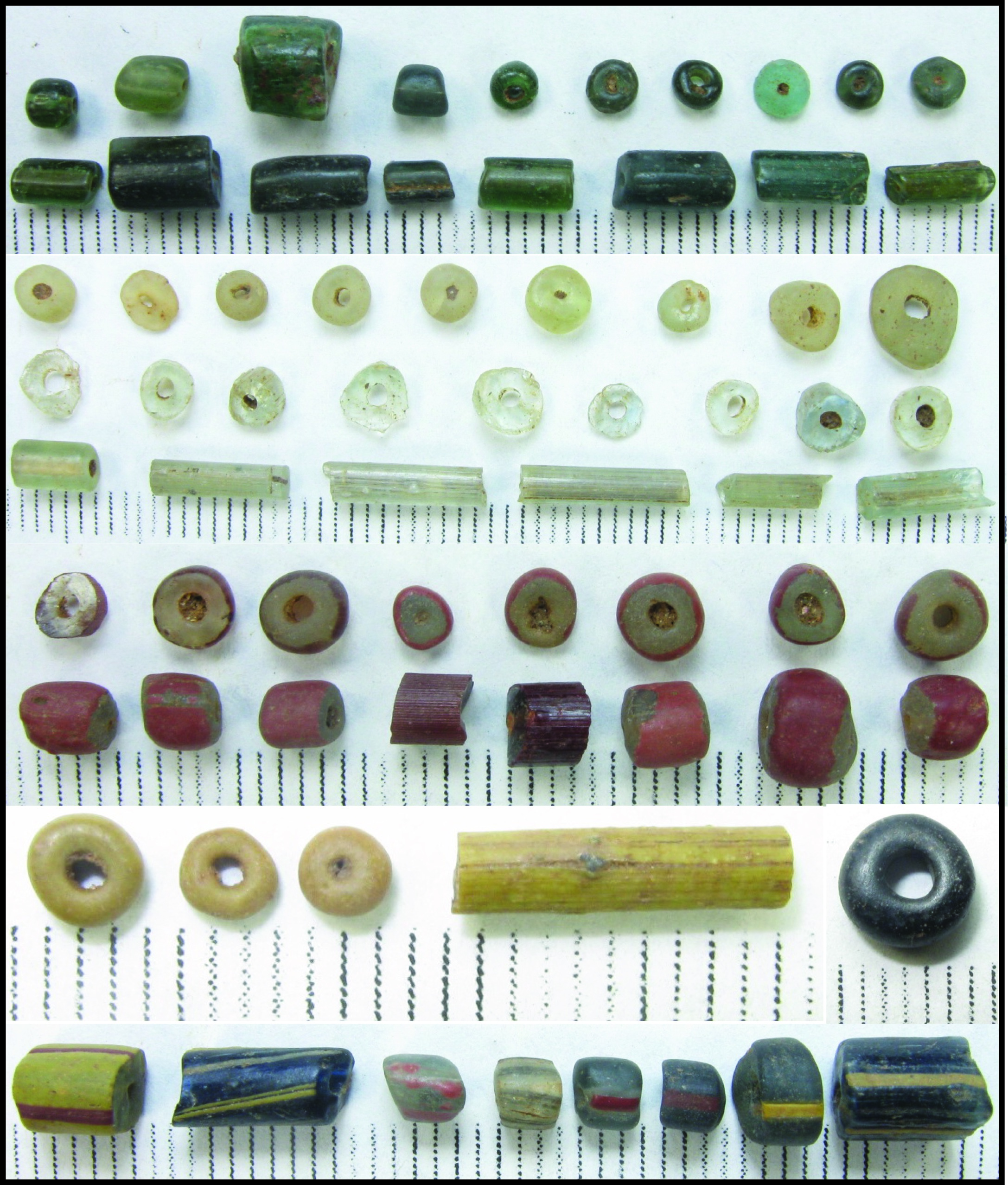

The majority of the beads are less than 0.2 inches (5 millimeters) across, and are colored blue, green, red, yellow or multicolored, Babalola said. [How 8 Colors Got Their Symbolic Meanings]

The researchers found that many of the beads, primarily the blue ones, were made "almost exclusively" from materials that are found near Igbo-Olokun, they wrote in the study. For instance, these beads had a high aluminum-oxide (also known as alumina) content, and previous researchers have pointed out that there are high-alumina sand deposits near Ile-Ife, Babalola said.

What's more, artisans might have used local ingredients, such as feldspar, to lower the heating temperature needed to melt glass in the crucibles, he said.

Glass world

The beads Babalola and his colleagues studied are called drawn beads, meaning artisans used a special technique that included using an air bubble to make the beads' holes. Craftspeople in India were making drawn glass beads as early as the fourth century B.C., but given the distance between India and modern-day Nigeria, Babalola and his colleagues propose that the West Africans developed the technique independently, he said.

However, more research is needed to support this claim, Babalola noted.

After the West African people made these beads, they traded them far and wide. Beads with the same components have been found in the upper Senegal region, including in Mali, and along the Niger River, the researchers wrote in the study.

The findings also show that West Africans were more technologically advanced than previously thought, Babalola said.

"We are talking about very sophisticated crafts," he said. "It takes someone who knows what he is doing and someone who has a very good understanding of science and technology to make this glass."

The study was published in the June issue of the journal Antiquity.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.