Meet the 'Eyeborg'

Rob Spence, a documentary filmmaker in Canada, has a radical prosthesis: a prosthetic eye fitted with a video camera.

Spence shot himself in the eye as a child, and after the cornea was irreparably damaged in 2007, he decided to get a prosthetic with more capabilities than the typical glass eye.

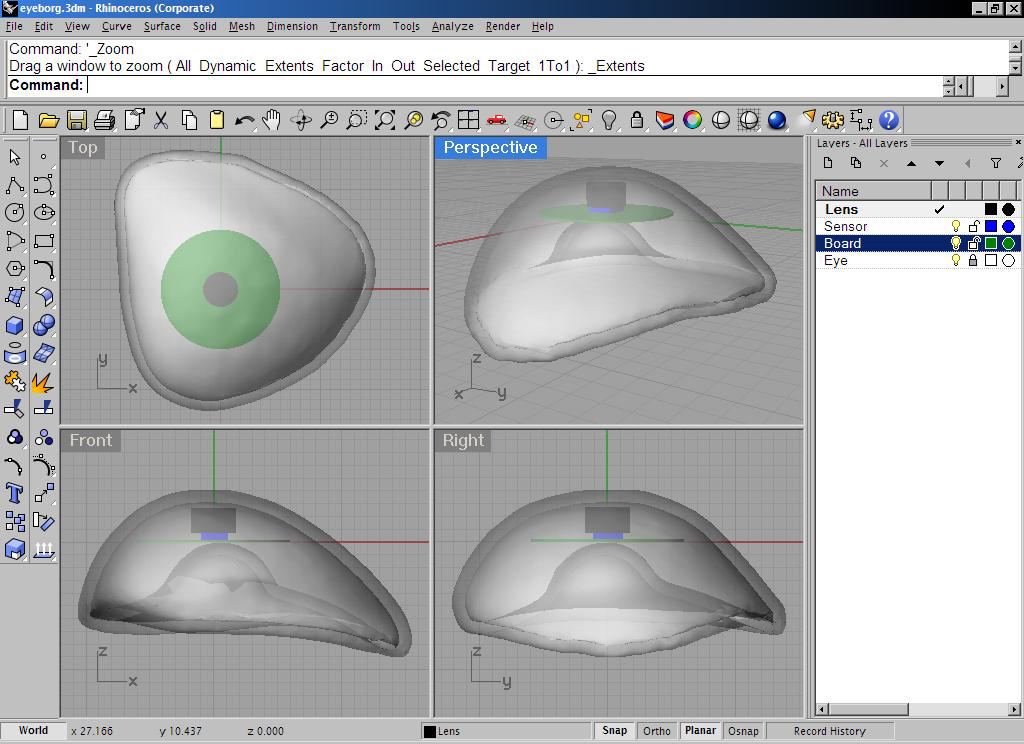

3D View

So he reached out to independent radio-frequency engineer and designer Kosta Grammatis, who helped him design a camera eye. The prosthetic was fitted to his eye socket, then a teensy camera was designed to lie behind it. Here, a 3D rendering of the eye.

Hidden components

The camera is also connected to a micro transmitter, a magnetic switch that allows Spence to turn it on and off, and a miniature circuit board that sends video to a receiver

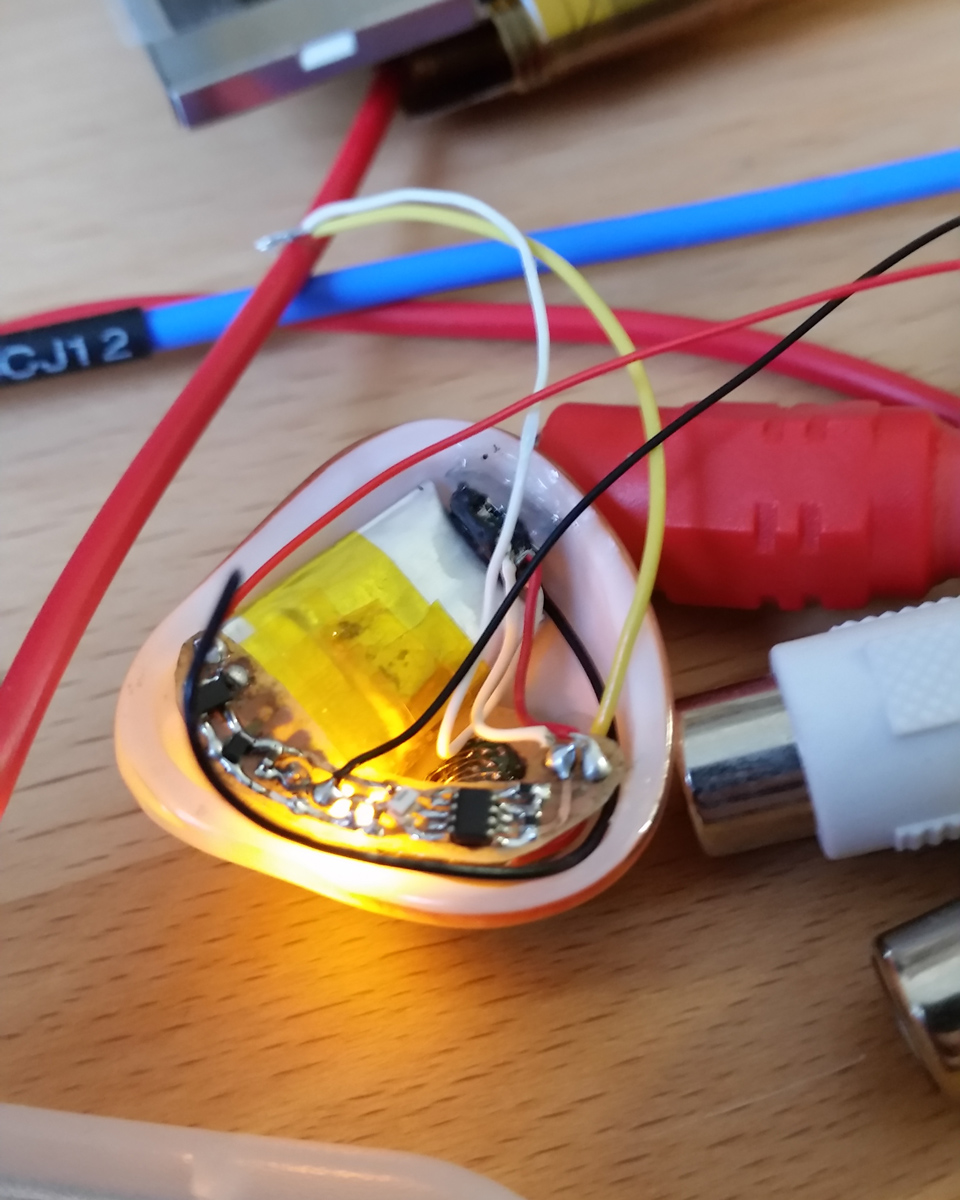

Tiny parts

Here, all the components that go into the eye laid out

Assembling the cyborg eye

The teensy circuit board was designed by engineer Martin Ling.

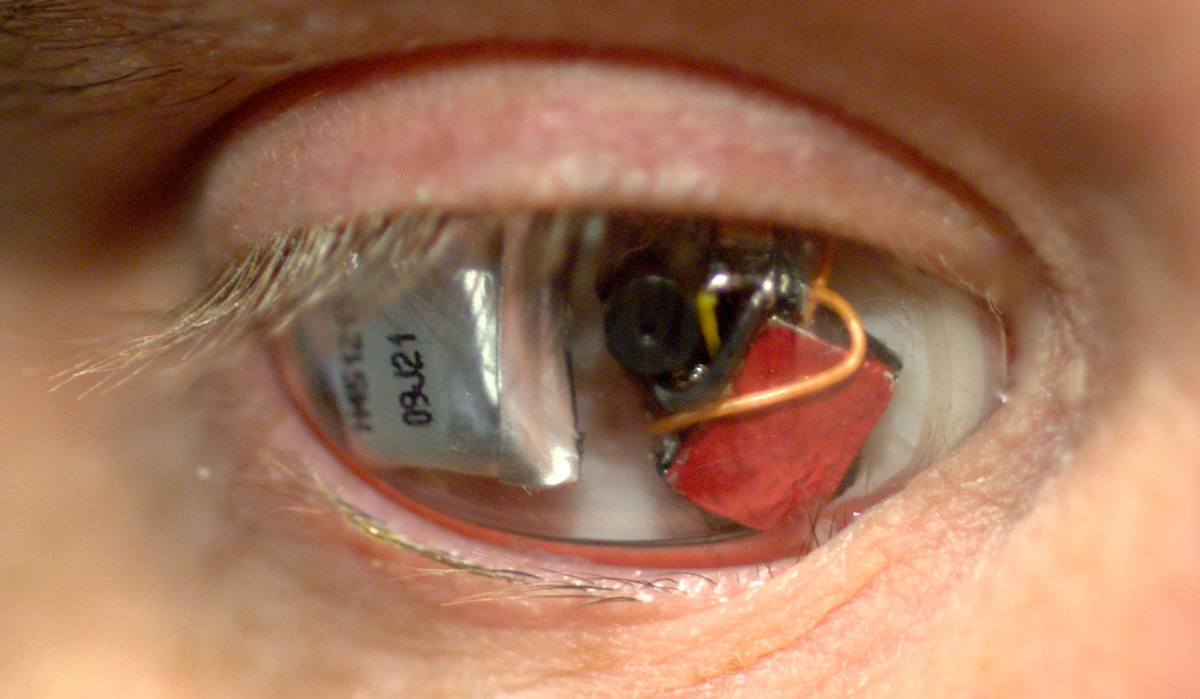

Eye spy

Here, an image of the eye taken out of the socket. The miniaturization of electrical components has helped make such innovations possible.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hidden eye

The prosthetic eye sits over the components. People are only aware of the camera once its light is turned on.

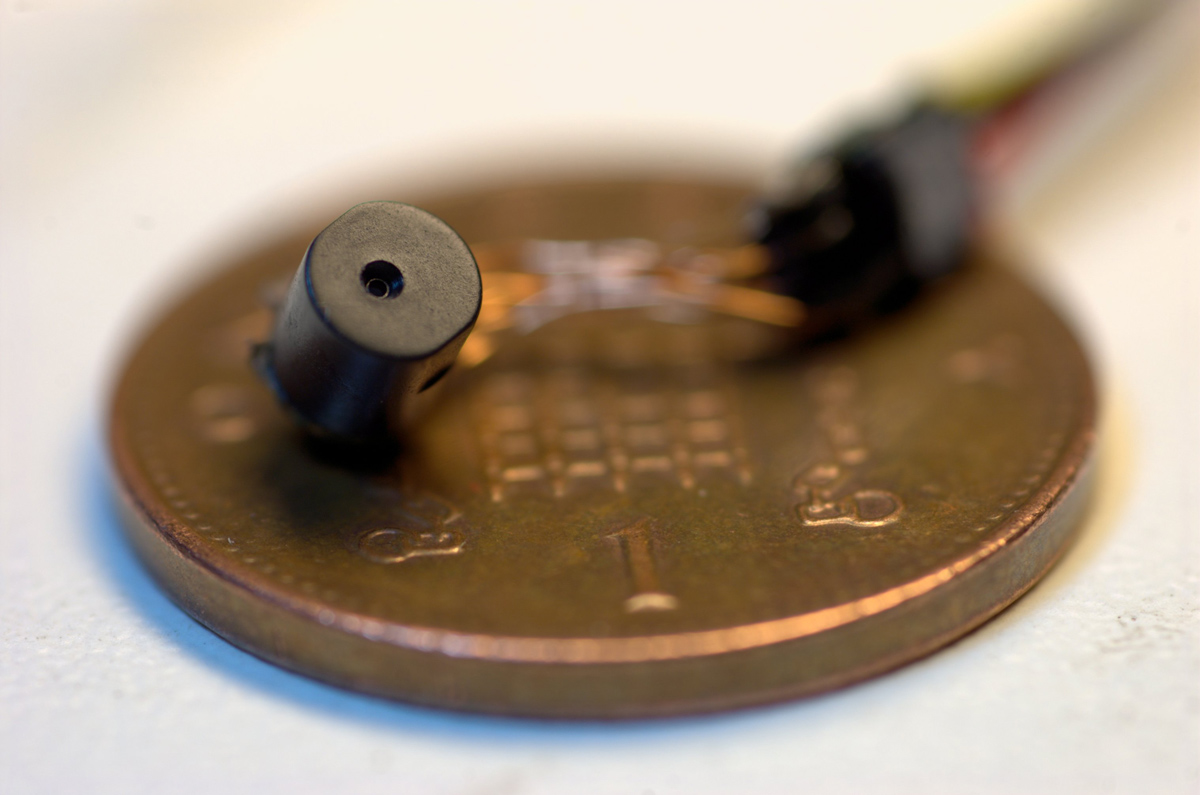

Miniature camera

The camera is unbelievably miniscule; the tiny black object is the camera, placed next to the prosthetic eye for reference.

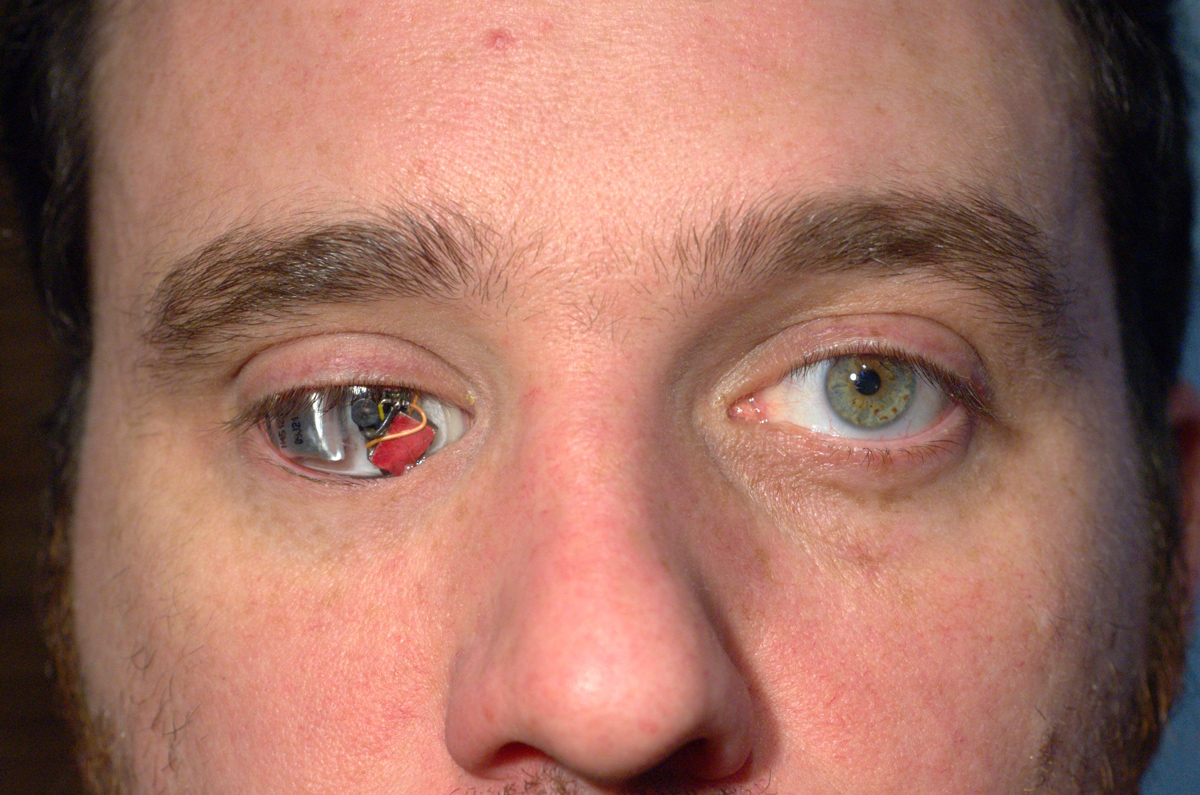

Part man part machine

Here, the components of the camera eye sit inside Spence's eye socket, without the prosthetic eye covering it. Spence is part of a small but growing group of people who are becoming cyborgs.

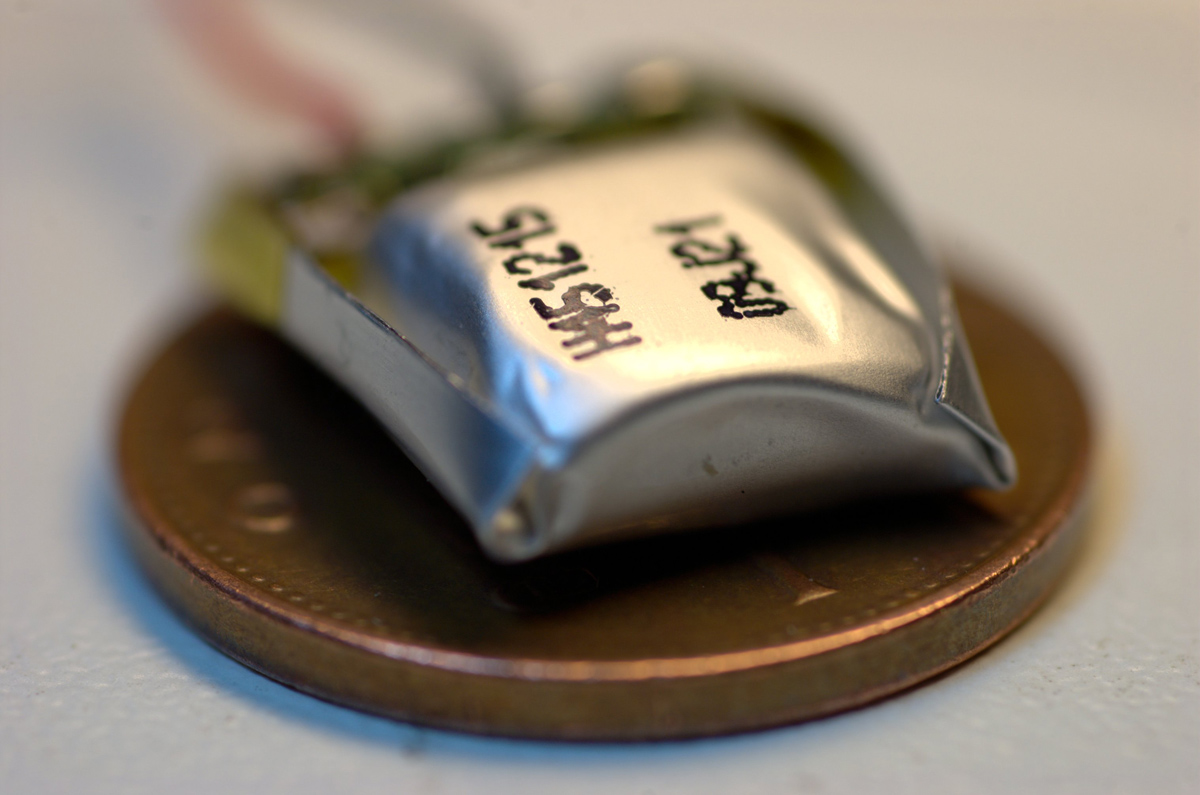

Charging the camera

A view of the tiny battery used to charge the video camera. The camera can only take about 30 minutes of video before it needs to be recharged.

True cyborg?

The tiny camera sitting on the backing for the prosthetic eye. The components are not connected to Spence's optic nerve or brain, so he isn't a true cyborg.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.