Poop Stains Help Scientists Track Antarctic Penguin Colonies

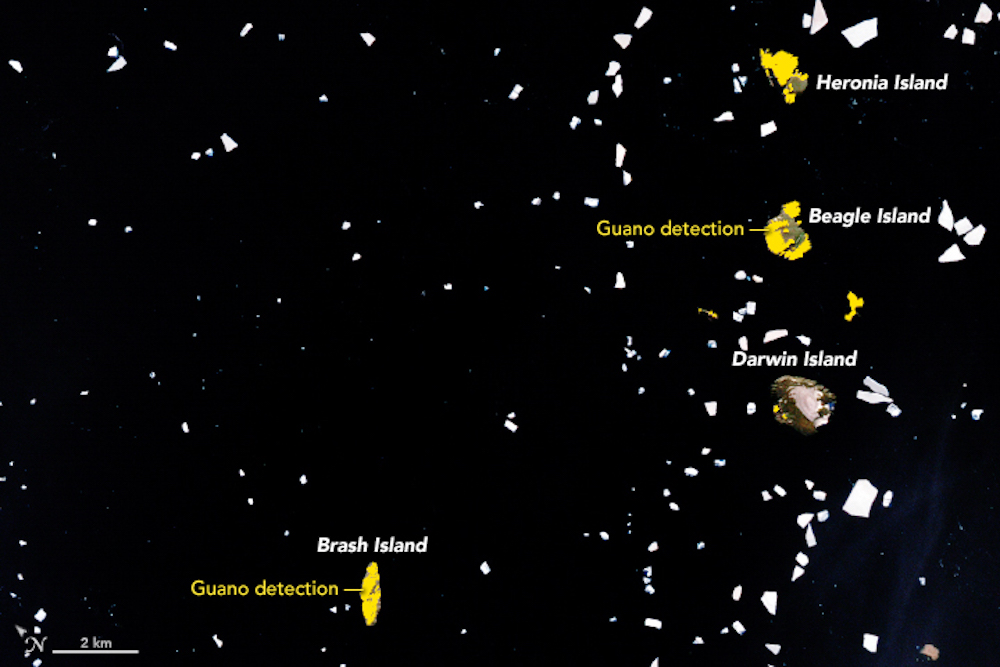

Adélie penguins in Antarctica nest in large colonies, and these groupings leave behind massive poop stains on the icy landscape — marks that are so large they can be tracked by satellites.

For more than 30 years, scientists have used these poop (known as guano) stains as markers to monitor the status of penguin populations. NASA's Earth-observing Landsat satellites have enabled researchers to track penguin populations and find dozens of previously unknown colonies. Scientists have collected Landsat data, along with data from finer-resolution commercial satellite imagery and field research, into an online database that follows Adélie penguins across Antarctica.

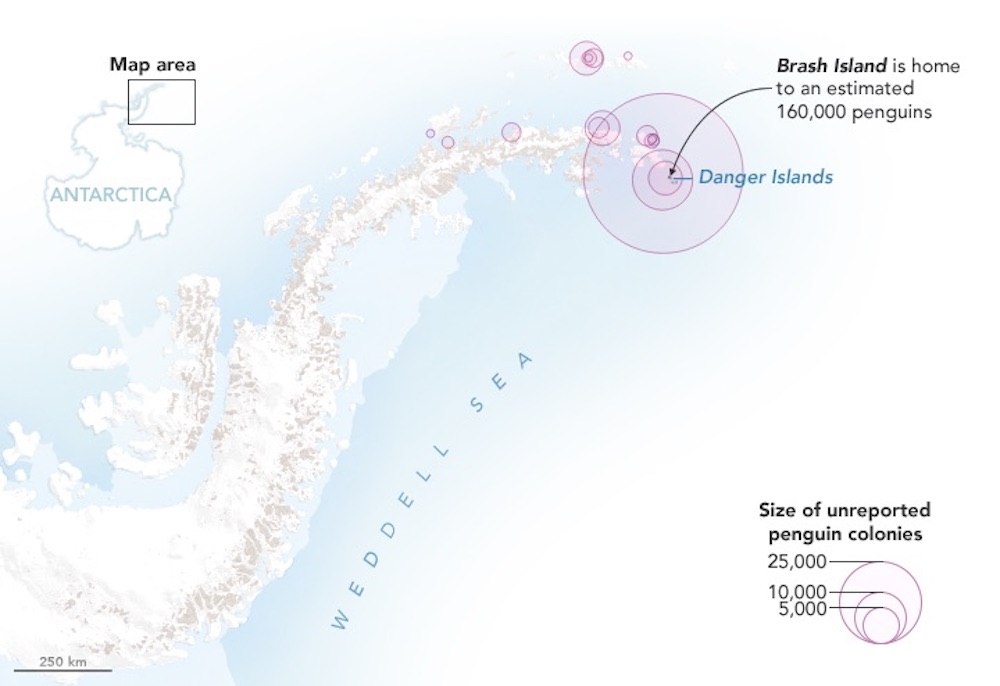

The guano-tracking satellites have helped researchers discover some large colonies in areas like the Danger Islands, which are rarely surveyed because sea-ice cover makes travel to the islands difficult. [In Photos: Adélie Penguins of East Antarctica]

"We're far from a point where satellites are going to make fieldwork irrelevant. Instead, it has made fieldwork more efficient," Heather Lynch, an ecologist at Stony Brook University in New York who works on the satellite project, said in a statement.

Lynch and NASA scientist Mathew Schwaller, who first suggested using Landsat to track penguin droppings, have used satellite images to identify thousands of penguins that were not previously accounted for. The algorithm, developed by Schwaller, pinpoints rocks in parts of Antarctica that have the color marker of guano stains: a pinkish hue.

On Brash Island alone, the scientists counted roughly 166,000 penguins. Another 23,000 penguins were found on Earle Island and 7,000 on Darwin Island, all thanks to the automated technique that searches for penguin guano in satellite images.

According to the researchers, the satellite algorithm detects 97 percent of penguins in Antarctica. However, the satellite searches alone may not detect smaller penguin colonies, because Landsat images have a pixel size equivalent to a square about 98 feet by 90 feet (30 meters by 30 meters) in size. Field observations and finer-resolution imagery are therefore still necessary to help detect colonies that have fewer than 3,000 breeding pairs, NASA said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Original article on Live Science.