Parkinson's May Begin in Gut Before Affecting the Brain

Parkinson's disease, which involves the malfunction and death of nerve cells in the brain, may originate in the gut, new research suggests, adding to a growing body of evidence supporting the idea.

The new study shows that a protein in nerve cells that becomes corrupted and then forms clumps in the brains of people with Parkinson's can also be found in cells that line the small intestine. The research was done in both mice and human cells.

The finding supports the idea that this protein first becomes altered in the gut and then travels to the brain, where it causes the symptoms of Parkinson's disease.

Parkinson's disease is a progressive movement disorder, affecting as many as 1 million people in the United States and 7 million to 10 million people worldwide, according to the Parkinson's Disease Foundation.

The protein, called alpha-synuclein, is abundant in the brain. And in healthy nerve cells, it dissolves in the fluid within the cell. But in Parkinson's patients, alpha-synuclein folds abnormally. The misfolded protein can then spread through the nervous system to the brain as a prion, or infectious protein. In the brain, the misfolded protein molecules stick to each other and clump up, damaging neurons. [6 Foods That Are Good for Your Brain]

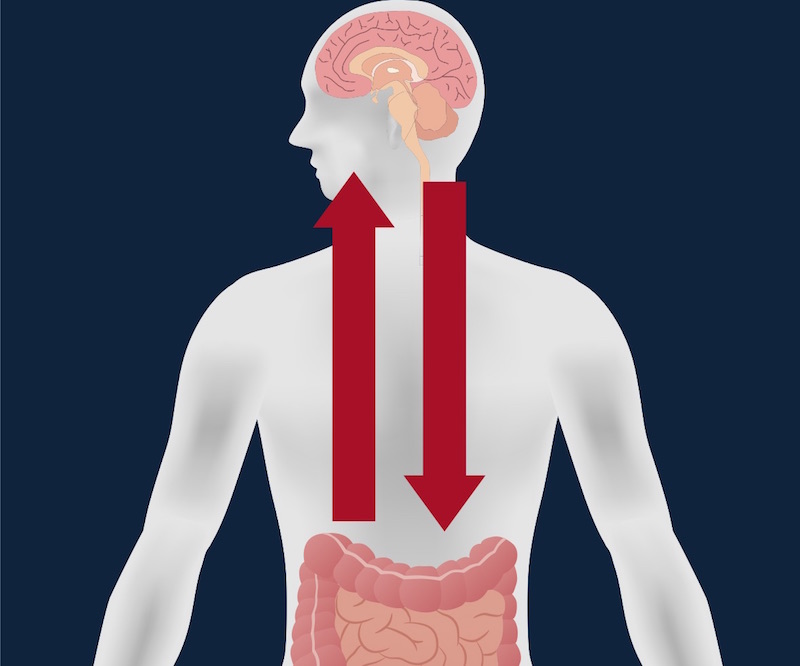

In 2005, researchers reported that people with Parkinson's disease who had these clumps in their brains also had the clumps in their guts. Other research published this year looked at people who had ulcers and who underwent a surgery that removed the base of the vagus nerve, which connects the brain stem to the abdomen. These patients had a 40 percent lower risk of developing Parkinson's later in life compared with people who didn't have their vagus nerve removed.

Both findings suggested the prion may originate in the gut.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But one puzzle remained: how the proteins that became altered in the gut could spread to the brain. The protein had been found in the lumen, or the space inside the gastrointestinal tract, but "nerves are not open to the lumen," said gastroenterologist Dr. Rodger Liddle, senior author of the new paper, appearing today (June 15) in the journal JCI Insight, and professor of medicine at Duke University in North Carolina.

A key clue to how the protein may move from the lumen into nerve cells came in 2015. Liddle's team discovered cells in the lining of the small intestine that "acted a lot like nerve cells," Liddle said. The cells were endocrine cells, meaning they produce hormones, but they contained neurotransmitters and other proteins normally found in neurons. These cells even appeared to branch out in a similar way that neurons do, to communicate.

When placed near neurons, these endocrine cells behaved a lot like neurons – the endocrine cells moved toward the neurons, and fibers sprouted between the cells, connecting them, Liddle said. The process was captured in a time-lapse video featured in the 2015 study in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

"It was only afterwards that we started putting these things together — these cells have a lot of nerve-like properties, [so] let's see if they also contain alpha-synuclein. And if they do, maybe they could be the source of Parkinson's disease," Liddle told Live Science. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain]

Now that Liddle's team has shown that the endocrine cells do, in fact, contain the alpha-synuclein protein, the researchers want to establish that the endocrine cells of Parkinson's patients carry the malformed version of the protein, Liddle said.

If they can establish that, Liddle said, they can envision how the corrupted proteins causing Parkinson's disease could spread from the gut lining to the brain, possibly via the vagus nerve.

Previous research has shown that people exposed to certain pesticides and bacteria are more likely to get Parkinson's. Liddle said that one possibility is that these agents may affect the nerve-like endocrine cells in the gut, altering the structure of the alpha-synuclein protein inside the gut cells.

"Maybe it's bacteria, maybe a toxin that people ingest. Maybe they affect the endocrine cell and that corrupts the alpha-synuclein protein, and that spreads from the cell to the vagus nerve to the brain," Liddle told Live Science.

For now, many "maybe's" remain. But if further research supports the hypothesis, it could point the way to new ways to diagnose Parkinson's disease early on, as well as to new approaches to treatment, Liddle said.

"It's possible that if it starts in the gut, then you could create treatments that prevent abnormal alpha-synuclein formation in these cells," Liddle said. "It's possible you could develop dietary ways of treating those cells because those cells are lining the intestine. At this point, it's difficult to imagine, but we will see."

Originally published on Live Science.