25 cultures that practiced human sacrifice

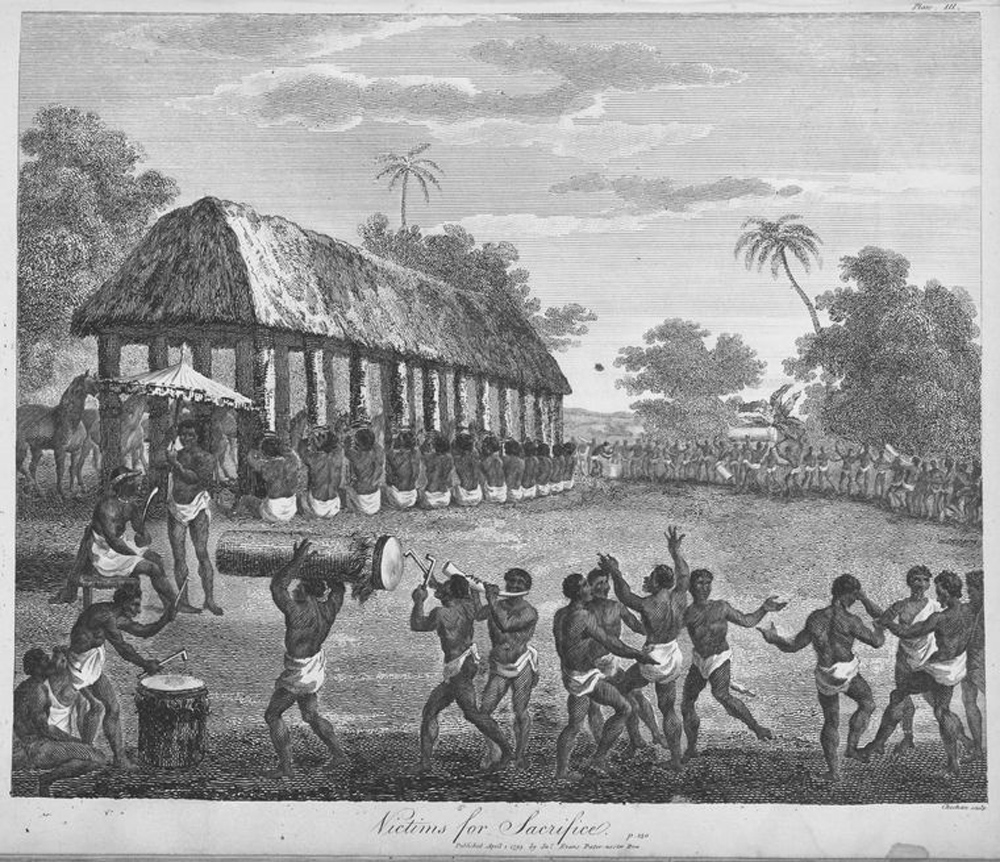

Hawaii clubbing?

Human sacrifices were performed in Hawaii as late as the 19th century. It may have served as a way for elite members of the island to help maintain their control over the population. Europeans who visited the island recorded the practice, with one famous painting showing a person being clubbed to death while lying on a rock. It's possible, however, that these accounts were exaggerated as a way to depict Hawaiian culture as savage and justify desires by Europeans and Americans to control the island.

Archaeologists have found that, as early as A.C. 1300, temples in Hawaii were being built with altars where sacrifices, either of humans or animals, could be made.

Ancient Romans

Ancient Roman writers claimed that human sacrifices were made during Rome's early history. After the Romans were defeated at the Battle of Cannae in 216 B.C., a battle that allowed an army from Carthage to temporarily occupy a large part of Italy, the Romans resorted to human sacrifice. "A Gaulish man and a Gaulish woman and a Greek man and a Greek woman were buried alive under the Forum Boarium," wrote the Roman writer Titus Livius (died A.D. 17) in his book "History of Rome" (translation by Canon Roberts).

Greeks sacrificed to Zeus

Textual references and archaeological remains indicate that the ancient Greeks, at times, practiced human sacrifice. In 2016, a 3,000-year-old skeleton of a male teenager was found at an altar dedicated to Zeus at Mount Lykaion in Greece. Archaeologists believe that the teen may have been sacrificed to Zeus, an idea supported by ancient texts that tell of child sacrifices that were made on the mountain.

Moche sacrifice

The Moche, who flourished in Peru between roughly the first and eighth centuries A.D., frequently practiced human sacrifice. They placed the victims in tombs and temples. At a temple now called Huaca de la Luna (Shrine of the Moon), the remains of dozens of sacrificed individuals have been discovered.

Dahomey kingdom

Human sacrifice was practiced by the rulers of the West African kingdom of Dahomey, which flourished between roughly A.D. 1600 and 1894, when the French conquered it and incorporated it into their empire. How widely human sacrifice was practiced is a matter of debate. Nineteenth-century European and American accounts sometimes claimed that more than 1,000 people could be sacrificed at any one time. Modern-day researchers believe that the actual number was quite a bit lower.

Celtic sacrifices?

The Celts are a name for a variety of groups who thrived throughout Europe, and parts of the Middle East, during ancient and modern times. Celtic groups gradually converted to Christianity after the first century A.D. Ancient Roman writers claimed that the Celts practiced human sacrifice on a large scale before they converted to Christianity and that their human sacrifices were sometimes carried out by the Druids, a people who served a variety of roles, sometimes performing religious functions in Celtic groups.

Modern-day archaeologists doubt that human sacrifice was practiced on a large scale by the Celts, if it was performed at all. Researchers point out that the Gauls, one of the largest Celtic groups, was conquered by the Romans, giving them an incentive to portray the Gauls as savages who would benefit under Roman rule. In 2015, a large 2,500-year-old Celtic tomb, possibly of a prince, was discovered that yielded many fantastic treasures; however, no human sacrifices were found.

The Nazca

The Nazca culture flourished in Peru between roughly 100 B.C. and A.D. 800. They are famous for constructing the Nazca Lines, thousands of geoglyphs scratched on the desert floor that show geometric designs as well as images from the natural world and human imagination. While most famous for their geoglyphs, the Nazca also practiced human sacrifice; Archaeologists have found the remains of trophy heads, as they call them, at several Nazca sites. Archaeologists believe that many of these trophy heads come from prisoners, who were executed and then had their heads chopped off.

Vikings sacrificed slaves

The Vikings occasionally sacrificed slaves after their owner had died. In Flakstad, Norway, archaeologists found the burial of 10 people, some of whom were beheaded. Analysis of their diet revealed that the beheaded individuals consumed more fish-based protein and those with their heads on consumed more protein from dairy and land-based animals. The team believes that the beheaded individuals were likely sacrificed after the death of their owners.

The remains of five human sacrifices, four of them young children, have also been discovered at the Viking fortress at Trelleborg in Denmark. The fortress dates back about 1,000 years; however archaeologists with the National Museum of Denmark believe that at least some of the victims were sacrificed sometime before the fort was constructed.

Carthage infants

Carthage is an ancient city in modern Tunis, in North Africa. Founded by the Phoenicians, a seafaring people who originated in the Eastern Mediterranean, the city contains a controversial burial ground known as the Tophet (the name comes from the Hebrew Bible), which has thousands of urns containing the cremated remains of infants. Some researchers believe that many of the infants were sacrificed, a claim supported by writings from ancient Greek and Roman historians. However, in 2012, a study of the skeletal remains found that few if any of the infants were sacrificed, a finding that some researchers dispute.

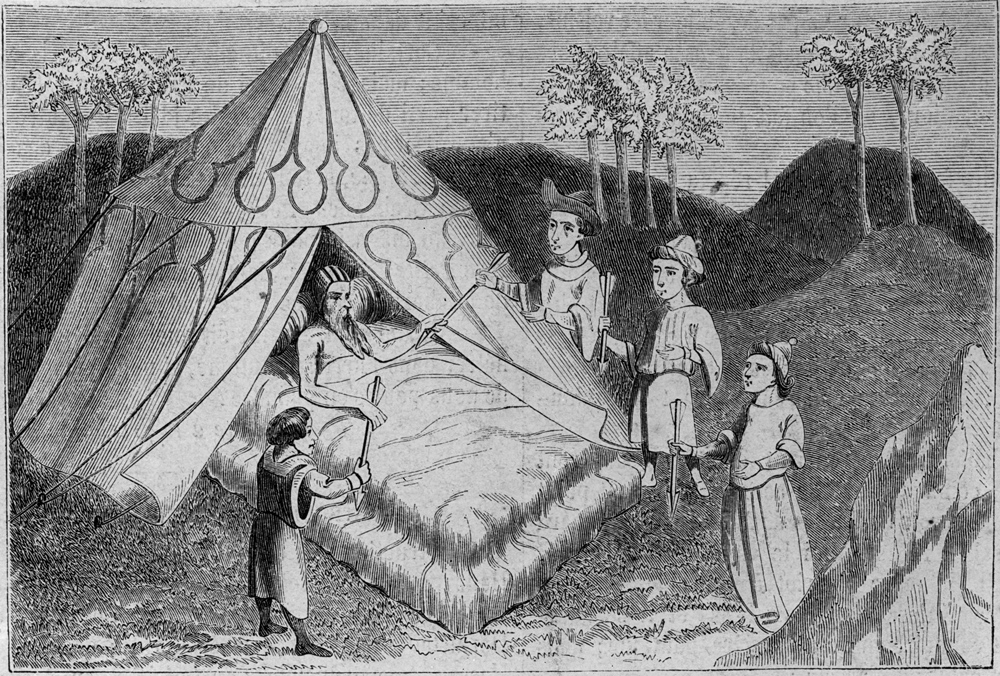

Mongol invaders

At their peak around 700 years ago, the Mongols controlled a vast amount of territory that stretched from East Asia to Europe. Most of the surviving accounts of the Mongols come from people the Mongols conquered, fought against or otherwise had hostilities with. Some of these accounts claim that the Mongols practiced human sacrifice. How often the Mongols undertook human sacrifice, or if it was practiced at all, is a matter of debate among researchers.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.