Is It Time to Rethink How We Search for Alien Life?

WASHINGTON — From the lovable, candy-munching E.T. to the deadly Xenomorphs from the "Alien" movies, science-fiction stories are bursting with all kinds of alien encounters. But in reality, we've yet to achieve contact — though not for lack of trying.

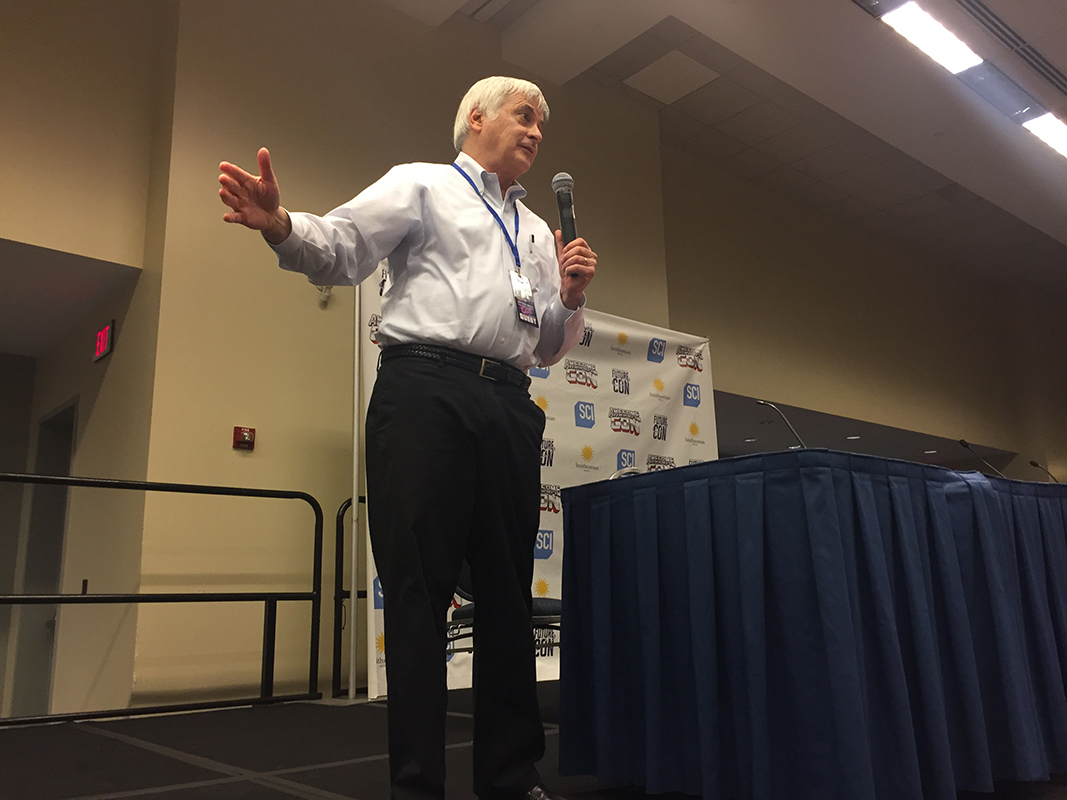

Plenty of scientists are looking for signs of extraterrestrial life — intelligent or not — using a variety of methods, Seth Shostak, senior astronomer at the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) Institute, told an audience here on June 18 during a talk at Future Con, a festival that highlights the intersection between science, technology and science fiction.

But the more our own technology moves forward and the more humans explore the rapidly evolving concept of synthetic intelligence (smart machines), the more experts suspect that intelligent extraterrestrial life could be advanced in ways that would stymie current efforts to find them, Shostak said. [Greetings, Earthlings! 8 Ways Aliens Could Contact Us]

However, perhaps the first question to ask is why people are so fascinated by the idea of alien life — particularly alien invaders, Shostak suggested. This preoccupation with an unseen extraterrestrial threat may be an echo from our distant past, when early humans learned that survival frequently depended on being able to imagine and prepare for attacks from predators or enemies that you couldn't see, he said.

What we now know about the universe suggests that it's very unlikely that humanity is the only form of life in it.

"Work from the last 20 years shows that there are planets all over the place," Shostak said. In fact, NASA announced yesterday (June 19) that the Kepler Space Telescope mission has discovered 219 more exoplanets (planets orbiting stars other than our sun), bringing the total of planets discovered by Kepler to 4,034, Space.com reported.

Most stars — 70 to 80 percent of them, by some estimates — probably host planets, Shostak added. With an estimated 100 billion stars in our galaxy, that gives us around 1 trillion planets in the Milky Way galaxy alone. Data from Kepler suggests that about one in five of these planets is Earth-like — rocky and capable of supporting liquid water and possibly life, "so now you have 100 billion planets in our galaxy that are sort of like Earth," Shostak said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

And with recent studies hinting that there may be as many as 2 trillion galaxies in the observable universe, that adds up to a lot of planets that might host some form of life.

When you look at it that way, "saying, 'I don't believe in aliens' is a daring position to take," Shostak said.

Signs of life

There are three methods most commonly used by scientists to search for alien life, according to Shostak. The first is straightforward enough — and is also the one that's most popular with sci-fi writers: "Just go out and find it," he said. This includes missions to send spacecraft to destinations such as Saturn's moon Enceladus, where probes would sample water vapor from surface plumes to see if they hold anything interesting. [13 Ways to Hunt Intelligent Aliens]

The final method — and the one practiced by Shostak and his SETI Institute colleagues — is eavesdropping on radio signals that an alien civilization might broadcast.Another method is to image distant planets with very large space telescopes capable of detecting enough detail to provide scientists with data about their atmospheres. Big telescopes — such as the James Webb Space Telescope, expected to launch in October 2018 — could allow astronomers to analyze the spectrum of light surrounding a far-off planet for evidence of atmospheric oxygen or methane, both of which are known to sustain life on Earth.

"That's how you find intelligent life," Shostak said.

Alien A.I.?

All of these parameters offer scientists a reasonable range of variables for discovering life — but only as long as that life is "the soft, squishy kind, like us," Shostak said. However, a sophisticated extraterrestrial civilization could theoretically have advanced far beyond that, creating forms of artificial intelligence housed in machinery, which simply don't have the same requirements as organic life.

"Machines live forever, and they can go anywhere — they don't care about oceans and atmospheres," Shostak said.

With that view, many of the factors that are currently thought to be indicators of life on other worlds, such as liquid water and a breathable atmosphere, are rendered irrelevant. As such, researchers would need to identify other signals to pinpoint which planets might harbor aliens, Shostak said.

But Shostak also offered reassurances, telling the Future Con attendees that at least they won't need to worry about scientists or the government concealing the news when alien life finally does appear — the story would be too big for them to hide it for long, he said.

"Will we all start singing 'Kumbaya' and just get along when that happens? I don't think so," Shostak said at Future Con. "But it'll change things. Forever after, you will know — as amazing as you are — that you're not the only miracle, you're not the only kid on the block. And I think that'll be very interesting to learn."

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.