Pew Pew Pew! Why Scientists Are Fired Up About Futuristic Space Lasers

WASHINGTON — Epic laser battles with highly concentrated beams of deadly light punching through starship hulls, slicing off limbs — or instantly vaporizing spacecraft, bodies and even planets — have been a much-loved and time-honored tradition in science fiction for many decades.

But anyone who has gripped a handheld laser pointer to lead a presentation or to tease a cat knows that lower-energy versions of lasers are quite common today. The focused light of lasers can be used for microscopy, to provide targets for weapons, to perform certain types of delicate surgery or to create spectacular visual displays at rock concerts.

And lasers are also frequently used in space — not as weapons, but to help scientists conduct highly precise measurements and observations, a group of NASA engineers and designers explained in a panel on June 16 here at Future Con. [The Most Dangerous Space Weapons Ever]

If you've ever marveled at the highly detailed Martian topography in the geobrowser Google Mars, you have lasers to thank, said Luis Ramos-Izquierdo, an optical systems engineer at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

For four-and-a-half years, the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) used lasers to collect data on Mars' surface elevation, which was used to generate the most detailed global topographic map of any planet in our solar system, according to NASA.

Ice, ice baby

Closer to home, the Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI), scheduled to launch in 2019, will use laser technology to create 3D maps of Earth's forests and calculate their biomass, Ramos-Izquierdo said.

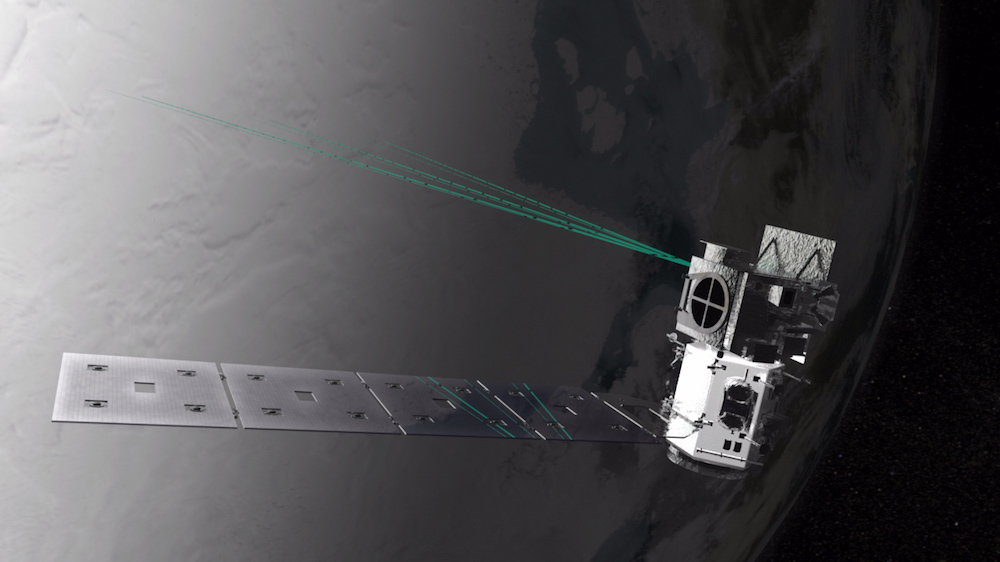

Another NASA mission using lasers to peer at Earth is named Ice, Cloud and Land Elevation Satellite-2 (ICESat-2). Scheduled to launch in 2018, ICESat-2 will use an array of six lasers — three paired beams — to track ice-sheet thickness and changes across Greenland and Antarctica, so that scientists can better estimate the risks posed by melting ice due to climate change, panel member Brooke Medley, a research associate with Earth Sciences Remote Sensing at the Goddard Space Flight Center, told the Future Con audience.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

ICESat-2 is continuing the work started by an earlier mission, ICESat-1, which was the first satellite to deploy lasers from space to measure surface elevation in the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, according to NASA.

The amount of ice cover in those two regions is enormous: Greenland's area is about three times the size of Texas, while Antarctica is roughly twice the size of the contiguous United States — far too big to accurately measure elevation changes from the ground or by airplane, Medley said. ICESat-2 will conduct multiple passes overhead at an altitude of 299 miles (481 kilometers), and its lasers will gather data that will enable researchers to calculate ice volume and track changes over time.

Another NASA satellite that resembles a mirror-studded disco ball — the LAser GEOdynamic Satellite (LAGEOS) — has been pinging back laser light beamed from Earth since it launched in 1976, returning data that enabled scientists to create the first models of Earth's gravitational field. Currently, there are two LAGEOS satellites in orbit, and their orbits are so stable that unless a piece of space debris collides with them, they'll be circling the planet for at least 1 million to 2 million years, according to panelist Evan Hoffman, a scientist with the Space Geodesy Project at Goddard.

In the moon's vicinity, the Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter instrument on the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter used lasers to gather billions of data points from the moon's surface while in orbit, enabling scientists to build the most detailed maps to date of lunar topography, Erwan Mazarico, a research associate with Planetary Studies at Goddard, said at the panel.

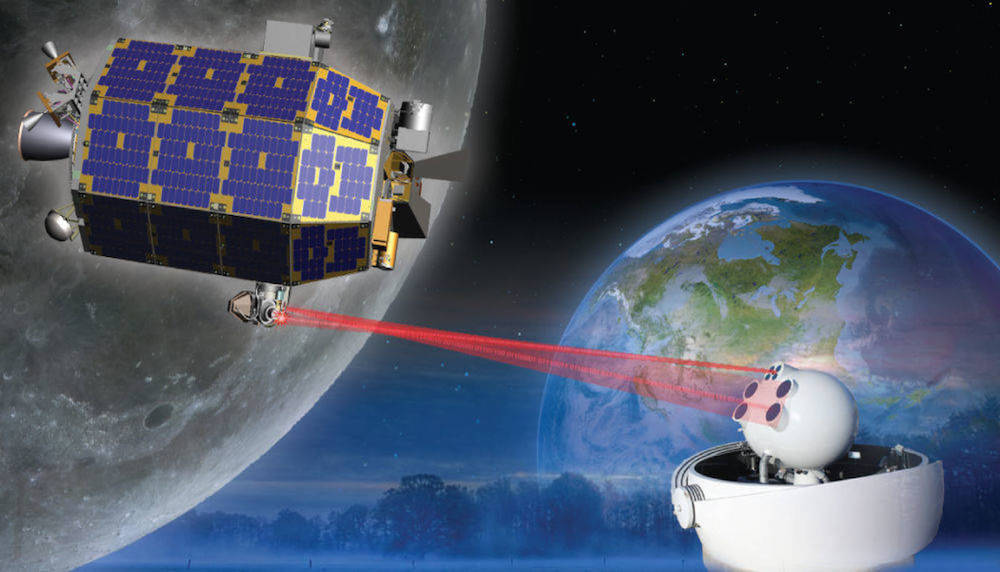

Lasers have also helped NASA researchers bring broadband to the moon, Jennifer Sager, lead system engineer and project manager with the Science and Planetary Operations Control Center at Goddard, told the panel audience. The Lunar Laser Communication Demonstration tested a two-way communication system between Earth and the moon using a pulsed laser beam, establishing a data download rate of 622 megabits per second, Sager said.

And researchers are even investigating whether lasers could be used defensively in space — not to battle invading extraterrestrials, but to nudge aside space debris that could damage equipment or threaten astronauts, Hoffman added.

Lighting the spark

Appearing at a conference like Future Con — where attendees are particularly enthusiastic about the real-world science behind their favorite sci-fi moments — allowed all of the scientists in the panel to touch upon some of the more interesting aspects of their research, even though the entire presentation was less than an hour, Mazarico told Space.com.

But each of the panelists could happily have spoken about lasers for much longer, Ramos-Izquierdo added.

"In reality, any one of us could talk for hours about our work and what we do — I could have gone on and on and on," Ramos-Izquierdo said.

"But it's good that they get a variety of the things we do at NASA, and maybe how it all comes together — for communication, for mapping the planet, for exploration. We gotta do all that work now, for science fiction to become real," he said.

Talking about space lasers at Future Con also brought NASA science directly to kids, perhaps encouraging the next generation of engineers and scientists, Mazarico told Space.com. And giving children a chance to meet the people behind the lasers might help them see themselves in those roles as adults, Medley added.

"We're just people that you could be passing in the street," she said. "Science isn't out of reach — it's something that is accessible for anyone."

Original article on Space.com.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.