Where the Mountains Meet: Take a Tour of Historic Fort Bowie (Photos)

Apache Pass

Throughout history, natural features such as mountain ranges, broad rivers and even desert lands have not only been barriers to human movement but have been contributing factors to human cultural conflicts. A perfect example of a natural environment contributing to deadly conflict between two human cultures can be found in the Sky Islands of southeastern Arizona, in a place known in history as Apache Pass.

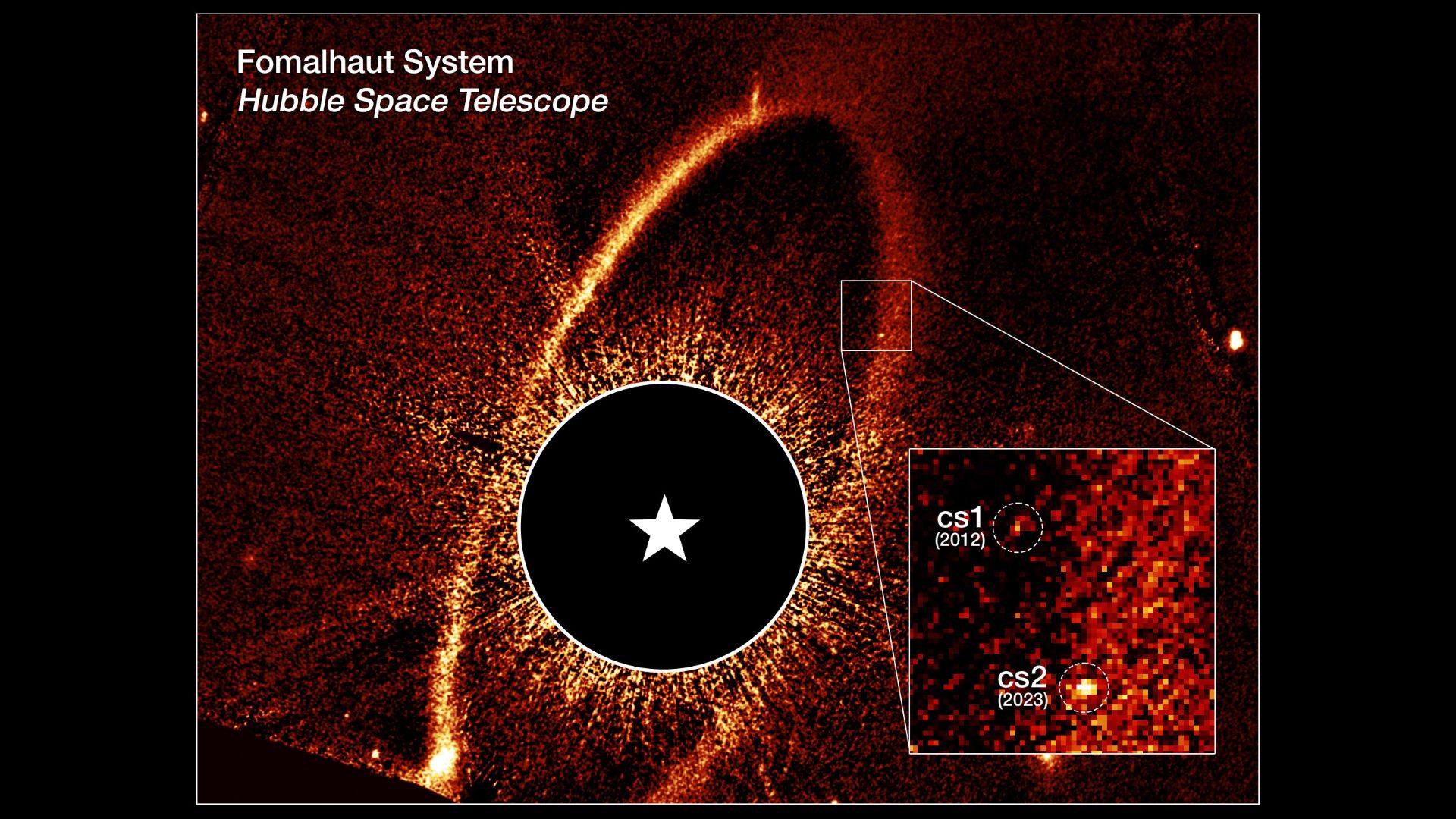

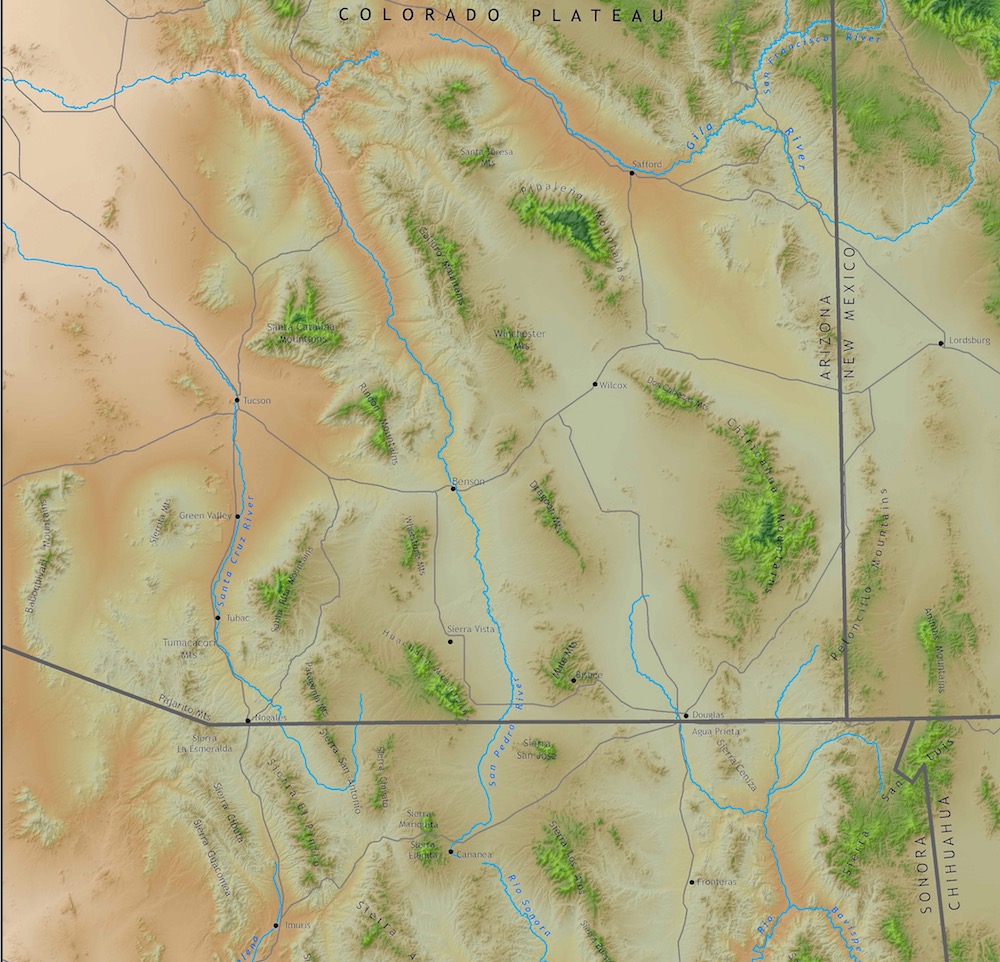

Sky Islands

Sky Islands are mountain ranges that have become isolated from each other by vast, sediment-filled valleys of grasslands or deserts that act as natural barriers, just like seawater, to the movement of plant and animal species. In the American Southwest and in northern Mexico, 27 Sky Islands are scatted over some 70,000 square miles (181,300 square kilometers) at the meeting point of two great mountain ranges: the Rocky Mountains of the north and the Sierra Madre Mountains of the south. Known as the Madrean Sky Island archipelago, this area has seen over eons of geological time the sinking of the valley floors, resulting in sky island mountain peaks rising to more than 10,000 feet (3,050 meters) in elevation above the dry Chihuahua and Sonoran Desert floors.

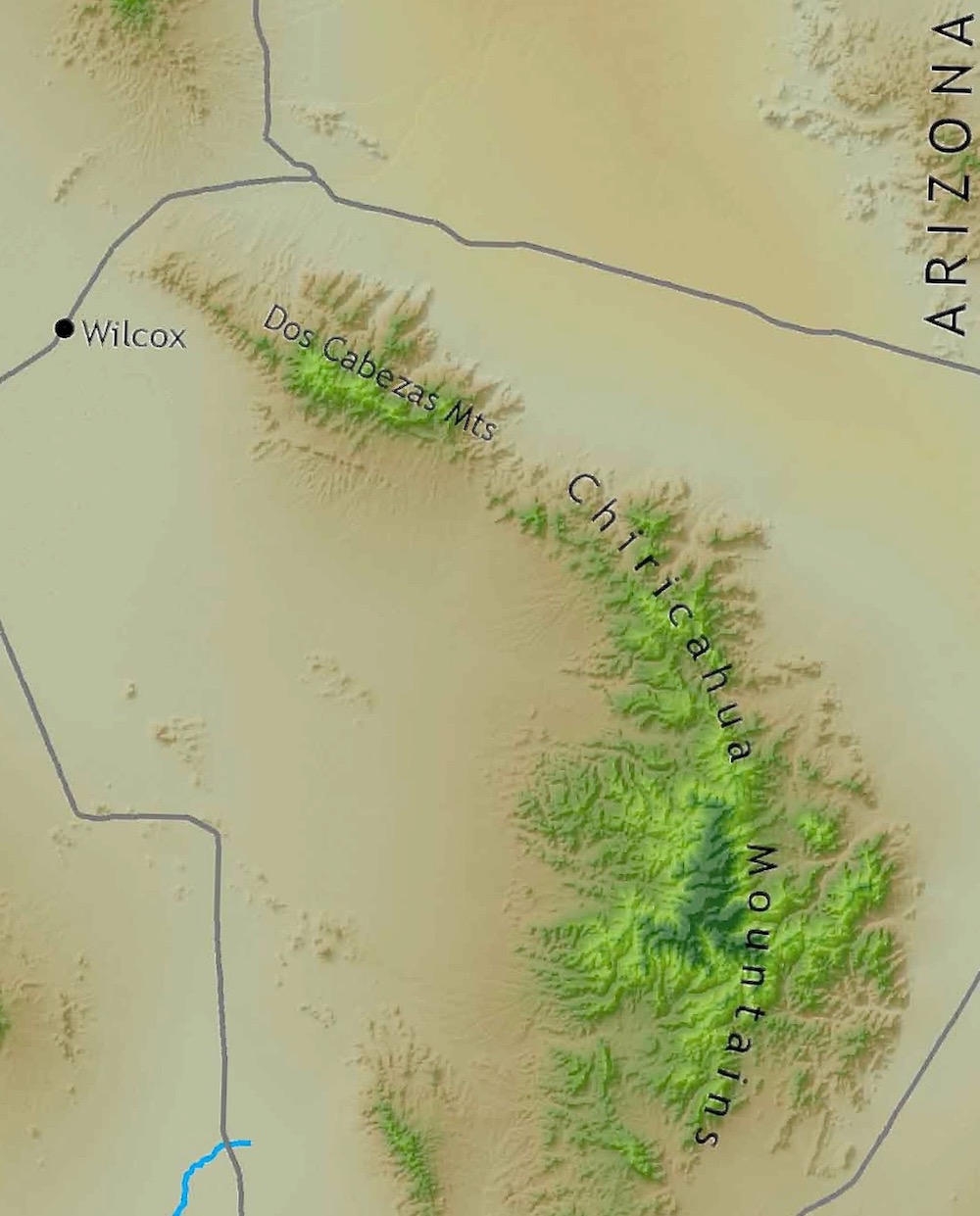

Where the mountains meet

Two of these Sky Islands, the Dos Cabezas Mountains and the Chiricahua Mountains, come together in the dry desert of southeastern Arizona and separate the San Simon Valley on the east from the Sulphur Spring Valley on the west. Where the two mountain ranges meet, a 3-mile-long (5 km) mountain valley once allowed the native Chiricahua Apache people, 16th-century Spanish Conquistadors and the 1840s American miners, settlers and soldiers to quickly move between the two desert valleys and avoid many days of traveling around the hot and dry desert lands surrounding the two Sky Islands.

Pass of Chance

Spanish Conquistadors called this valuable mountain valley "Puerto del Dado," meaning the "Pass of Chance." Conflict was common between the local Chiricahua Apache people and the Spanish soldiers who always took a dangerous chance each time they passed through this valley. The saddle of Apache Pass is at an elevation of 4,550 feet (1,387 m) with surrounding mountain peaks rising to a height of 5,250 feet (1,600 m). This elevation is at the upper elevational limit for a desert environment and the pass is populated with plant species common in desert, grassland and woodland habitats.

Freshwater source

But quick passage between two vast desert valleys was not the only reason that Apache Pass was so valuable to all the people living and traveling through this land. Just a few hundred yards west of the mountain's saddle, a natural spring of water (shown here) flowed year round. Apache Spring is the result of a fault zone, initiated more than 1 billion years ago and active throughout geological time. Extensive fractured and faulted rocks are dominant throughout this mountain valley and have long provided a channel for groundwater to constantly flow to the surface at Apache Springs over the millennia. In this vast desert region, a constant source of fresh water is priceless!

Go West

In the 1840s, when young men from around the world heard the call of Horace Greeley to "Go West, young man, Go West," a southern land route to the gold fields of California was needed. The only logical route passed through the American Southwest, but even in winter, the vast deserts were a challenge. Soon, gold miners and settlers alike began moving through Apache Pass for both its convenience and its constant source of fresh water. In 1857, the historic Butterfield Overland Mail Stage Line built a station, shown here, just half a mile west of the Apache Pass mountain saddle, as it began carrying both mail and passengers between St. Louis, Missouri, and San Francisco, California.

Human conflict

Two significant events would soon occur between the Chiricahua Apache people and the U. S. Army. The first occurred in January 1861, when the great Chiricahua chief, Cochise, was wrongly accused of raiding a local ranch. It would become known as the Bascom Affair and resulted in fighting between Chiricahua Apache warriors and the U.S. Army that would last for more than 20 years. The second, the Battle of Apache Pass, occurred in July 1862, when troops from the Union's California Column were attacked by warriors as they moved through Apache Pass toward the New Mexico Territory to battle Confederate soldiers during the American Civil War.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

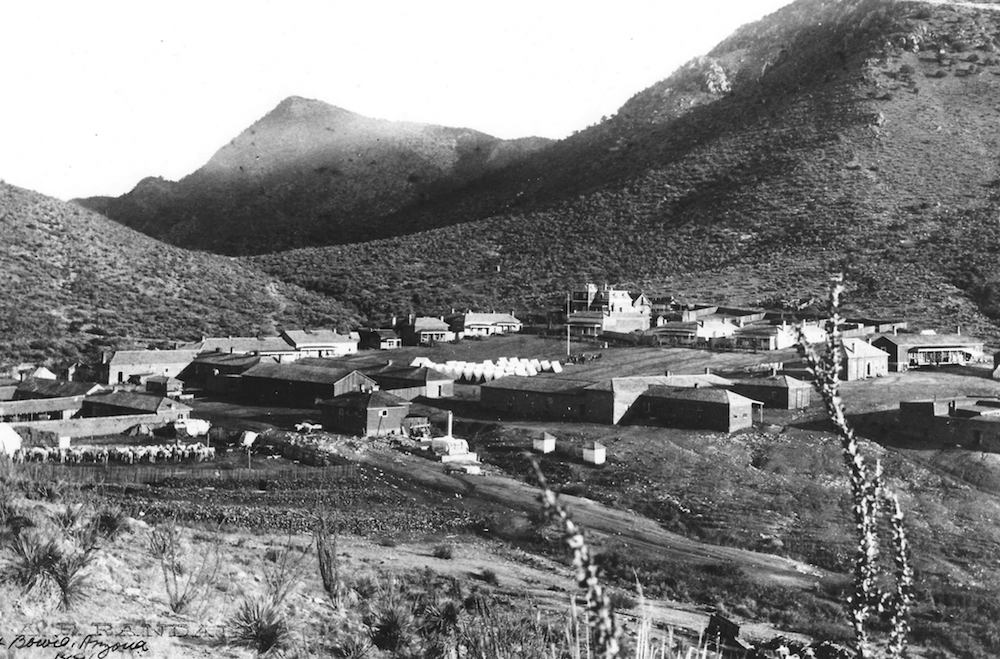

Fort Bowie camp

The California Column established a makeshift Fort Bowie camp in 1862. But with the growing movement of people and goods through this mountain valley, and the now all too common conflict with the local Chiricahua Apache people, the United States governments responded by building a more permanent outpost at the saddle of Apache Pass in 1864. The new outpost was named Fort Bowie in honor of Colonel George Washington Bowie, commander of the 5th Regiment California Column Volunteer Infantry.

Apache Wars

Fort Bowie became the center of military operations for the U.S. Army against the Chiricahua Apaches until the tragic Apache Wars ended in 1886. During that time, U.S. soldiers fought Apache warriors led by both hereditary chief Cochise and a Chiricahua shaman known as Geronimo. When the Apache Wars ended, Fort Bowie was a post with more than 50 adobe and stone buildings. A then-modern heliograph station was also present. Family picnics, a game of tennis and a concert by the post band were all a part of daily post life. By 1894, the need for Fort Bowie had come to an end, and the U.S. Army closed the post and abandoned the buildings.

Journey back in time

Today the old adobe walls of the second Fort Bowie site lie in ruin on the mountain's saddle. These remaining ruins are encased in protective limestone casings. Stabilization of the ruins began in 1964 by the National Park Service, and Fort Bowie National Historic Site was officially established in 1972. The park is some 1.56 square miles (4 square kilometers) in size, and offers visitors a unique glimpse into a time when an emerging country driven by its belief in "manifest destiny" encountered a courageous indigenous people fighting for their very existence.

Take a hike

Visitors to Fort Bowie today must put forth some physical effort. A 1.5-mile (2.4 km) hiking trail leads from the parking lot along Apache Pass Road through a biogeographic transition zone between the Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts and the Rocky and Sierra Madre mountains. The trail is rated "moderate" with just under a 200-foot (60 m) elevation gain between the parking area and the fort's ruins. An alternative ADA access to the visitor center is available.