Amazon's Delivery Drones Could Take Off from Beehive-Like 'Airport'

If Amazon's package-carrying drones ever become a reality, they may one day pick up deliveries from beehive-shaped buildings strategically placed in cities around the world, according to a patent application filed by the company.

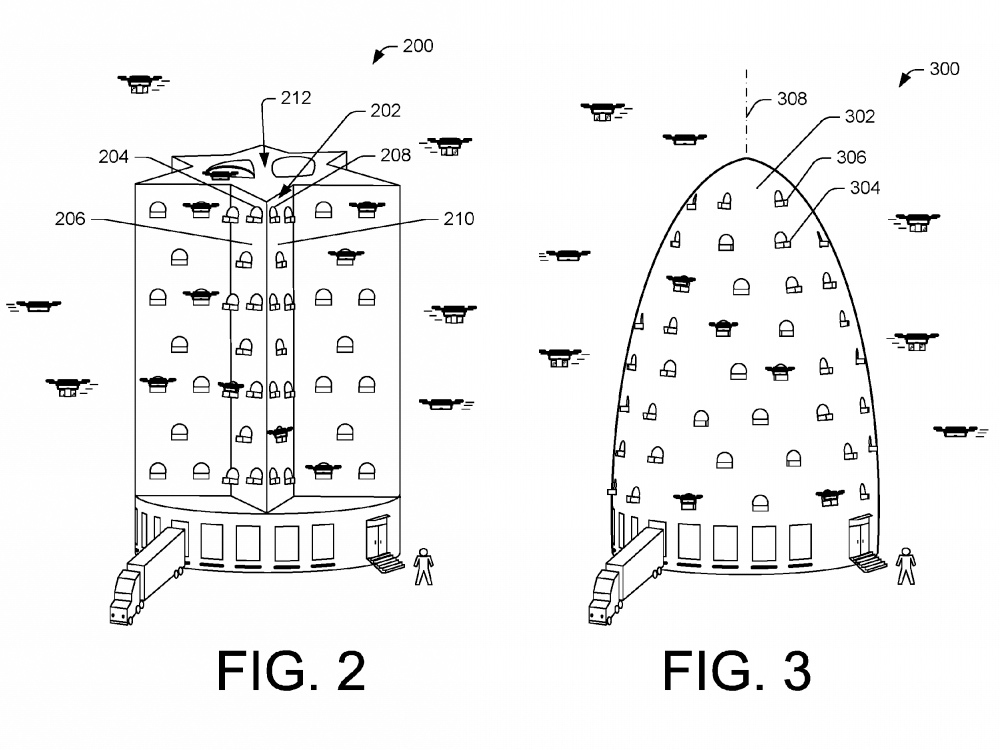

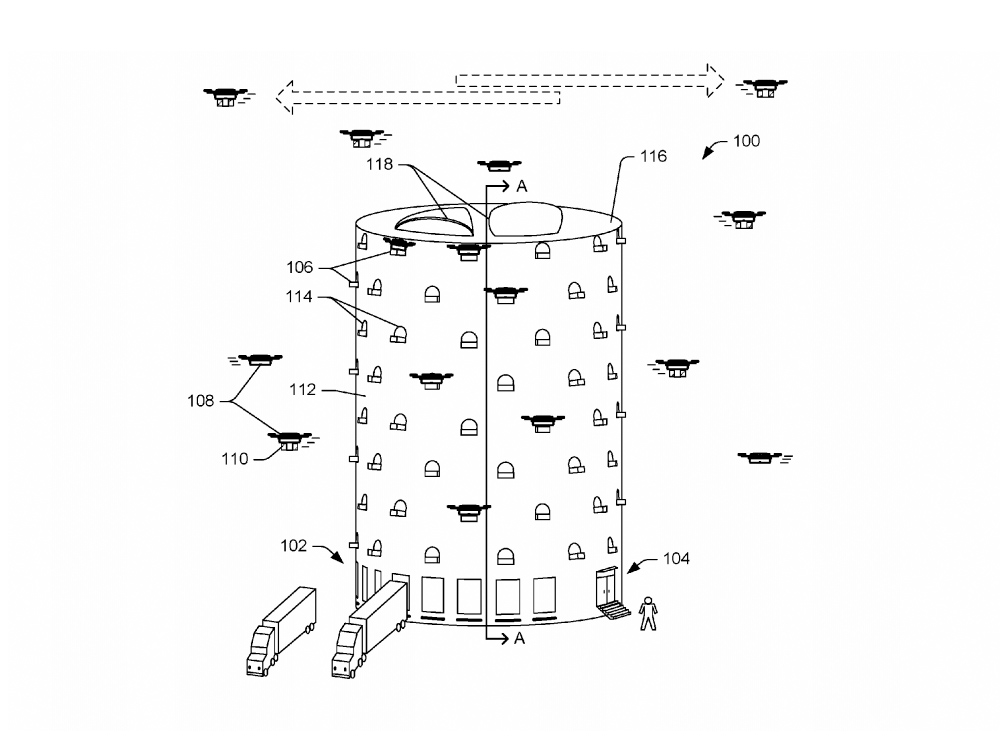

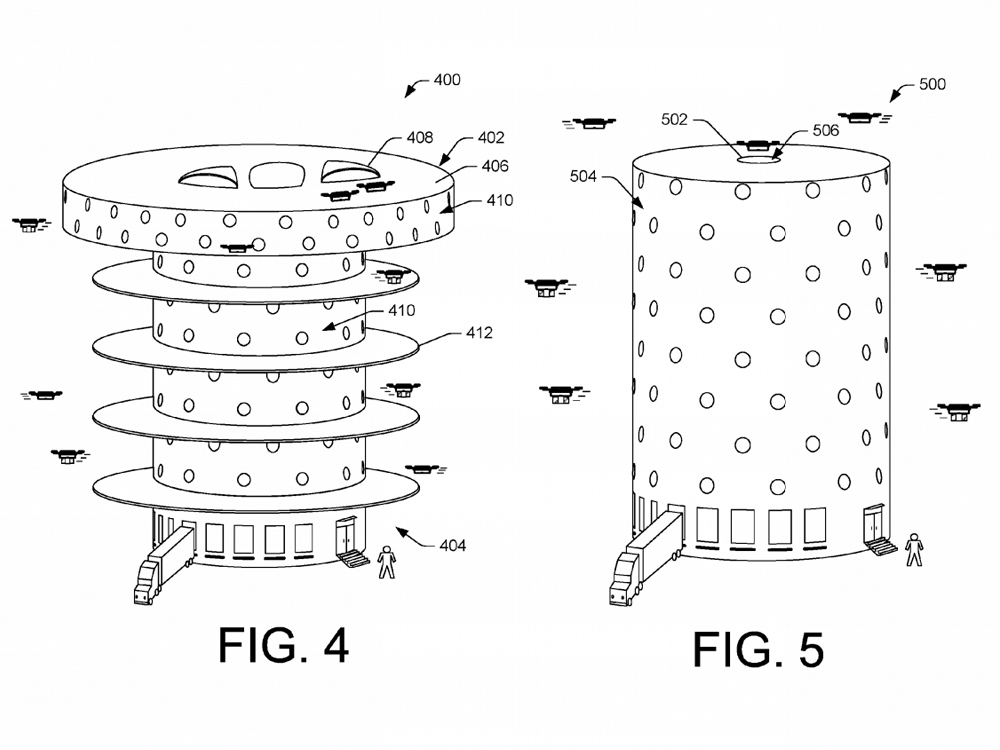

The patent, published online on June 22, describes something called the "multi-level fulfillment center for unmanned aerial vehicles," demonstrating how Amazon plans to take package delivery to the next level.

These days, Amazon's warehouses "are typically large-volume single-floor warehouse buildings," located on the outskirts of cities, the company wrote in the patent, which was filed in 2015. However, "these locations are not convenien[t] for deliveries into cities where an ever-increasing number of people live," Amazon said. [9 Totally Cool Uses for Drones]

If these warehouses could be built in cities, it would decrease delivery time for Amazon customers who live and work there, the company said. But, because real estate is limited in downtown areas, Amazon proposed a work-around: It could build a futuristic high-rise that would store retail items and serve as a base and airport for drones delivering customer orders.

The patent describes how the building would have multistoried platforms for drone landings and takeoffs. Just in case a drone ran out of power or malfunctioned, the company would place an "impact dampener," such as foam or a net, in strategic areas, Amazon said.

The company would stock the beehives' shelves the old-fashioned way — that is, by arranging freight delivery via trucks, rail or ships. Then, human personnel and robotic devices would unload and then later package orders, according to Amazon.

Moreover, if customers were to have time to stop by the center, they could access their orders at self-service locations, including lockers or staffed pickup rooms, according to the patent.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But the building's main reason for existing — for drone takeoff and delivery— steals the show. After an order is packaged, an "internal transport robot" — which could be a robot, elevator, conveyer belt or some sort of lifting mechanism — would move one of the drones from a holding area to a platform used for charging and takeoff, the patent said.

This step is key: It brings the drone to a higher location for liftoff, which saves the drone power because it takes energy to ascend to cruising altitude, according to the patent. The high takeoff platform will also take the constant "whirring" sound of drones away from street level, somewhat reducing noise pollution for pedestrians, the patent said.

But the patent design isn't perfect. According to The Verge, "Who’s going to want to live near a drone delivery tower if it makes so much noise? And what if drones start falling out the sky, making impromptu, and possibly fatal, deliveries?"

The Verge noted that Amazon has proposed putting "sound dampening treatments" on the drones' rotors, which could help reduce noise pollution even more, the company said.

Besides filing this patent, Amazon is hard at work on its drone endeavors. The company's unmanned aircrafts delivered two lightweight orders — a bag of popcorn and a TV streaming stick (a USB-like device) — in Cambridge, England, in December 2016, according to The Guardian. Amazon has also filed patents for flying warehouses, parachute-aided package delivery and mega delivery drones.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.