Boaty McBoatface Is Back! Here's What the Sub Found on Its 1st Mission

During the operation, Boaty bravely explored the Antarctic bottom water, one of the coldest abyssal ocean spots on the planet. (The abyssal zone ranges from about 13,000 to 20,000 feet, or 4,000 to 6,000 meters, deep, beyond sunlight's reach.)

The sub captured data on temperature, speed of water flow and underwater turbulence rates within the Orkney Passage in the Southern Ocean, before it returned to its base in the United Kingdom last week. [50 Amazing Facts About Antarctica]

"Fresh from its maiden voyage, Boaty is already delivering new insight into some of the coldest ocean waters on Earth, giving scientists a greater understanding of changes in the Antarctic region and shaping a global effort to tackle climate change," Jo Johnson, the U.K. minister for universities and science, said in a statement.

Boaty McBoatface became famous in March 2016, when the U.K.'s Natural Environment Research Council invited the public to brainstorm and vote on names for a new research vessel. To the surprise of the research council, the moniker "Boaty McBoatface" soon topped the charts by the time the poll ended a month later.

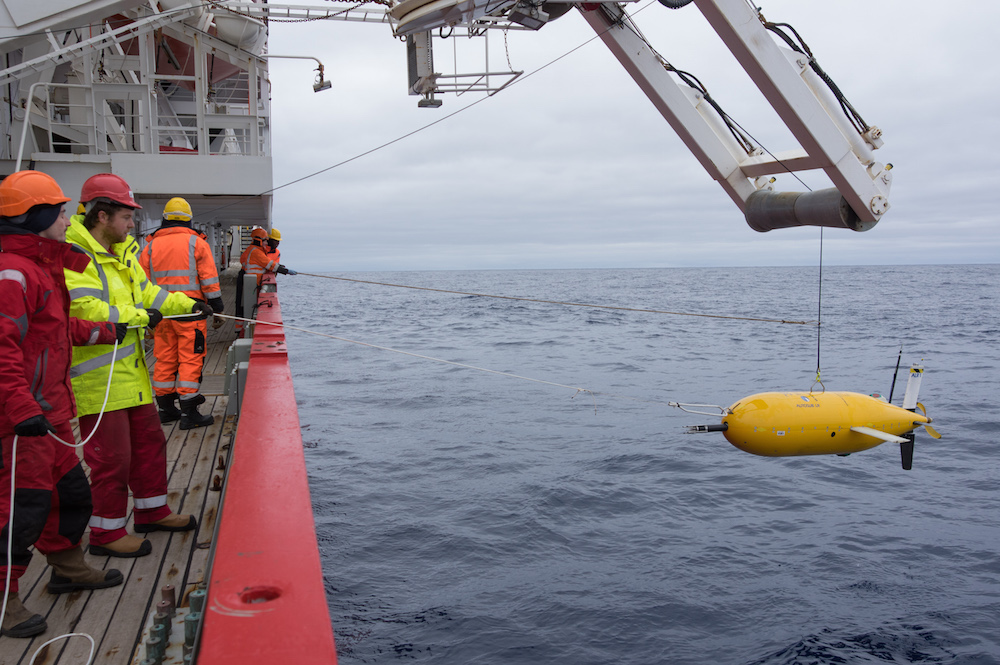

The research council opted for a compromise: The research vessel would be christened the "Sir David Attenborough," in honor of the famous British naturalist and broadcaster, while its yellow submersible would be called Boaty McBoatface.

Maiden mission

For its first mission, researchers aboard the Sir David Attenborough used Boaty, as well as a variety of instruments on the ship and underwater, to learn more about the environment along the Orkney Passage.

Once underwater, Boaty traveled back and forth along the Orkney Passage's floor, sometimes in water colder than 32 degrees Fahrenheit (0 degrees Celsius) and in currents as fast as 1 knot (1.1 mph, or 1.8 km/h) when it measured the intensity of the turbulence.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The submersible also encountered marine wildlife.

"At the start of one mission, whilst diving, Boaty encountered a swarm of krill so dense that the sub's echo sounders thought it was approaching the seabed, although it was only at 80 m [262 feet] depth, and returned to the surface," Povl Abrahamsen, a physical oceanographer with the British Antarctic Survey, said in the statement.

Warming currents

The currents measured by Boaty form off the coast of Antarctica when cold winds coming off the ice sheet cool the sea's surface. These cold, dense waters then sink and move northward, creating a key global circulation of ocean water, the researchers said. However, this Antarctic bottom water must flow through one choke point — the Orkney Passage — on its way from Antarctica's Weddell Sea to the Atlantic Ocean, the researchers said. [Antarctica: 100 Years of Exploration (Infographic)]

Evidence suggests that changing winds blowing across the Southern Ocean affect the speed of the seafloor currents carrying the Antarctic bottom water. Faster flows are more turbulent, and more turbulence tends to mix heat from shallower waters into the lower, colder waters. This warms the abyssal waters on their way to the equator, and can affect global climate change, the researchers said.

"The Orkney Passage is a key chokepoint to the flow of abyssal waters, in which we expect the mechanism linking changing winds to abyssal water warming to operate," said Alberto Naveira Garabato, the project's lead scientist and a professor of Earth and ocean sciences at the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom.

Boaty helped the scientists by collecting vast amounts of data from its underwater missions.

"Up until now, we have only been able to take measurements from a fixed point, but now, we are able to obtain a much more detailed picture of what is happening in this very important underwater landscape," Garabato said. "The challenge for us now is to analyze it all."

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.