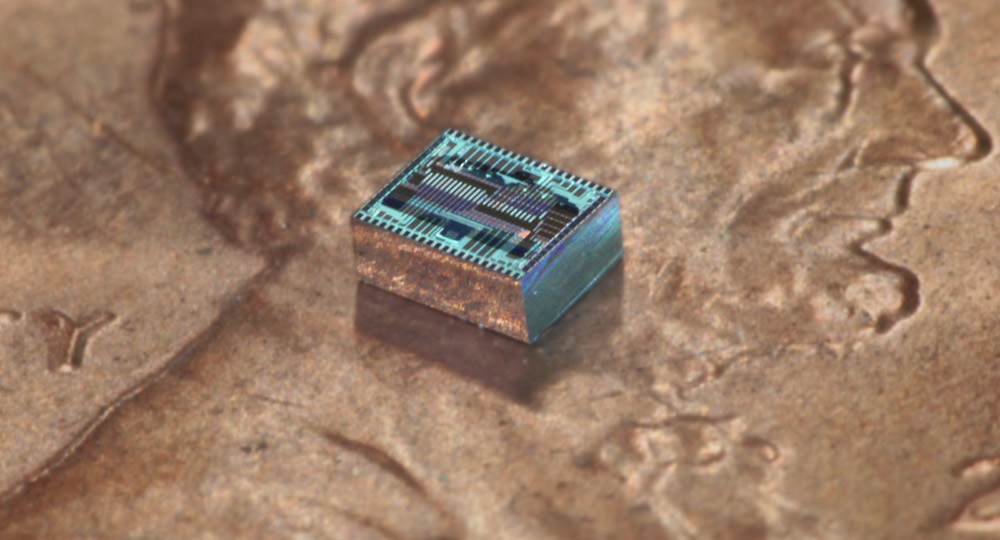

Tiny, Lens-Free Camera Could Hide in Clothes, Glasses

The device, a square that measures just 0.04 inches by 0.05 inches (1 by 1.2 millimeters), has the potential to switch its "aperture" among wide angle, fish eye and zoom instantaneously. And because the device is so thin, just a few microns thick, it could be embedded anywhere. (For comparison, the average width of a human hair is about 100 microns.)

"The entire backside of your phone could be a camera," said Ali Hajimiri, a professor of electrical engineering and medical engineering at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and the principal investigator of the research paper, describing the new camera. [Photo Future: 7 High-Tech Ways to Share Images]

It could be embedded in a watch or in a pair of eyeglasses or in fabric, Hajimiri told Live Science. It could even be designed to launch into space as a small package and then unfurl into very large, thin sheets that image the universe at resolutions never before possible, he added.

"There's no fundamental limit on how much you could increase the resolution," Hajimiri said. "You could do gigapixels if you wanted.” (A gigapixel image has 1 billion pixels, or 1,000 times more than an image from a 1-megapixel digital camera.)

Hajimiri and his colleagues presented their innovation, called an optical phased array, at the Optical Society's (OSA) Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics, which was held in March. The research was also published online in the OSA Technical Digest.

The proof-of-concept device is a flat sheet with an array of 64 light receivers that can be thought of as tiny antennas tuned to receive light waves, Hajimiri said. Each receiver in the array is individually controlled by a computer program.

In fractions of a second, the light receivers can be manipulated to create an image of an object on the far right side of the view or on the far left or anywhere in between. And this can be done without pointing the device at the objects, which would be necessary with a camera.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The beauty of this thing is that we create images without any mechanical movement," he said.

Hajimiri called this feature a "synthetic aperture." To test how well it worked, the researchers laid the thin arrayover a silicon computer chip. In experiments, the synthetic aperture collected light waves, and then other components on the chip converted the light waves to electrical signals that were sent to a sensor.

The resulting image looks like a checkerboard with illuminated squares, but this basic low-resolution image is just first step, Hajimiri said. The device's ability to manipulate incoming light waves is so precise and fast that, theoretically, it could capture hundreds of different kinds of images in any kind of light, including infrared, in a matter of seconds, he said.

"You can make an extremely powerful and large camera," Hajimiri said.

Achieving a high-power view with a conventional camera requires that the lens be very big, so that it can collect enough light. This is why professional photographers on the sidelines of sporting events wield huge camera lenses.

But bigger lenses require more glass, and that can introduce light and color flaws in the image. The researchers' optical phased array doesn't have that problem, or any added bulk, Hajimiri said.

For the next stage of their research, Hajimiri and his colleagues are working to make the device larger, with more light receivers in the array.

"Essentially, there's no limit on how much you could increase the resolution," he said. "It's just a question of how large you can make the phased array."

Original article on Live Science.