In Photos: Antarctica's Larsen C Ice Shelf Through Time

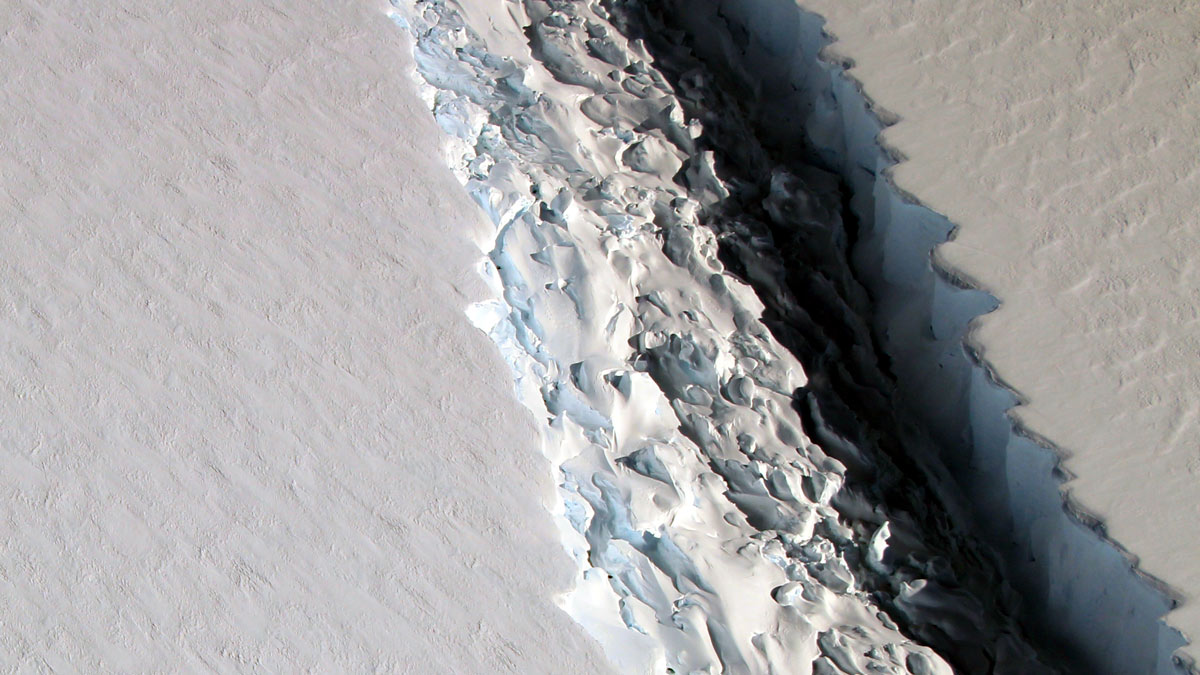

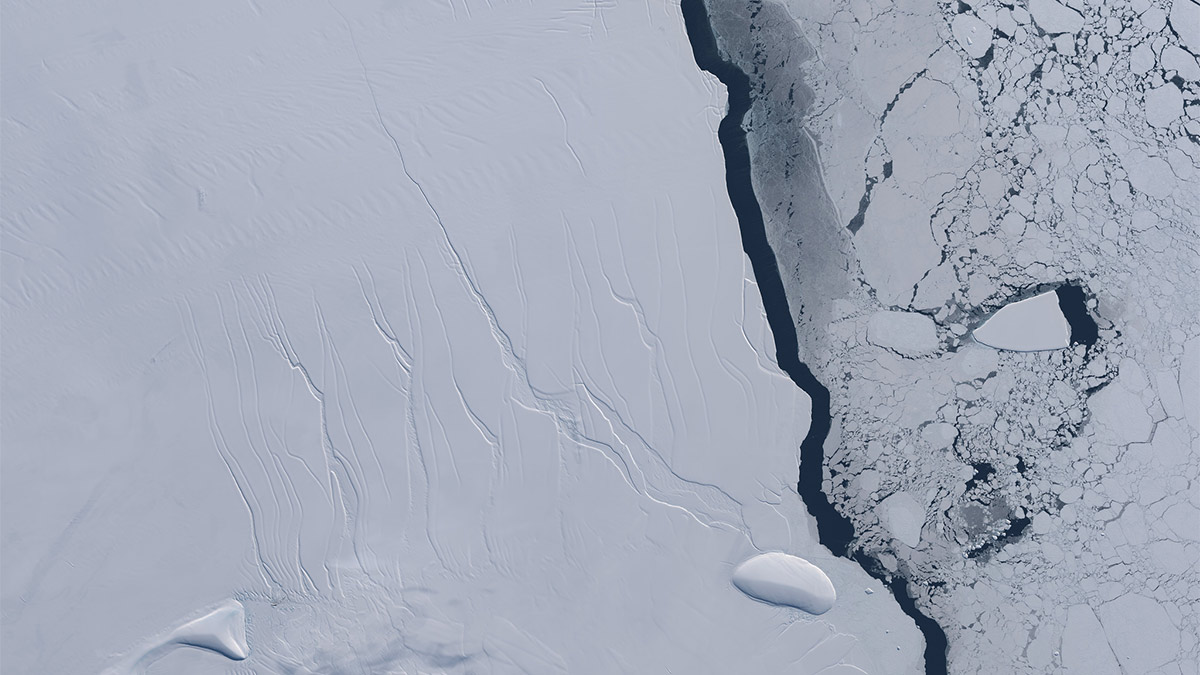

Hanging on by a thread

The Antarctic peninsula is made up of several ice shelves, including Larsen A, B and C. Whereas two of these ice shelves (A and B), which are floating extensions of land-based glaciers, collapsed in 1995 and 2002, respectively, Larsen C is still holding on … but only by a thread. Scientists say it could calve a Delaware-size iceberg at any moment now, as a rift continues to grow and the shelf speeds its Here, a snapshot of the rift in Larsen C, taken on Nov. 10, 2016; in early December 2016, the crack was 70 miles (112 km) long.

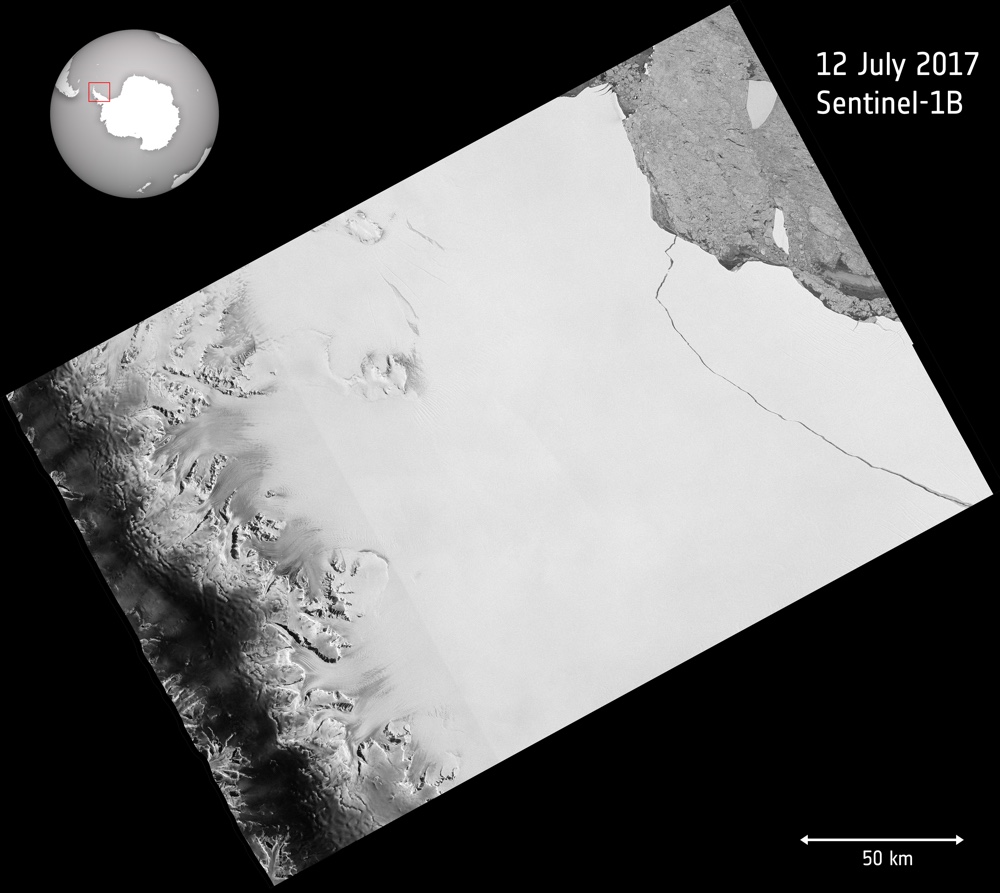

Iceberg Breaks Free

The European Space Agency's Copernicus Sentinel-1 mission detected the huge chunk of ice that broke off Antarctica's Larsen C ice shelf on July 12, 2017. The iceberg holds 1.1 trillion tons (1 trillion metric tons) of ice and would fill up Lake Erie twice, researchers say.

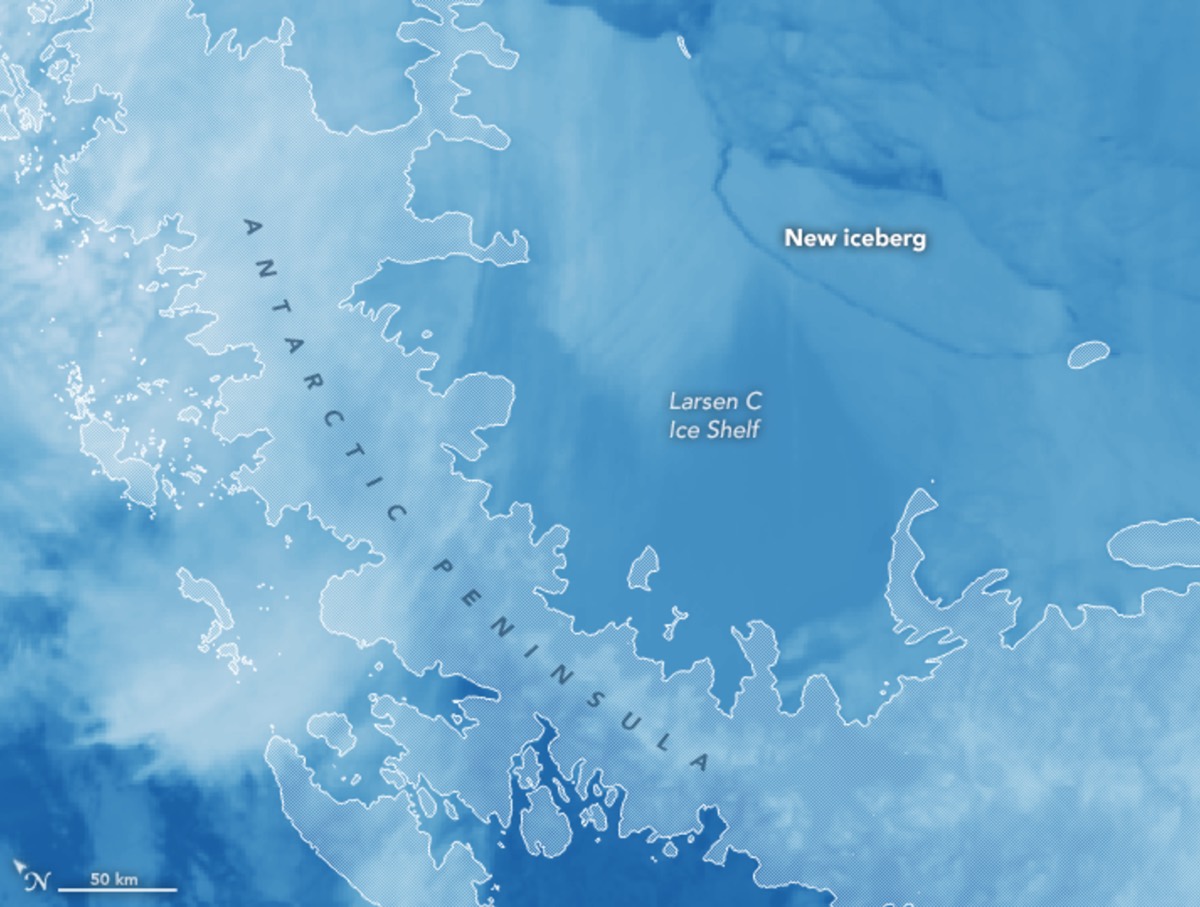

Bouncing baby ... iceberg

An instrument aboard NASA's Aqua satellite captured this image on July 12, 2017, revealing the giant iceberg that just calved from Antarctica's Larsen C ice shelf. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) measured infrared signals called "brightness temperature," which can distinguish between warmer and cooler surfaces. In the false-color image, the blue indicates the warmest surfaces, which include the new iceberg and the Larsen C ice shelf. The blue also shows areas of open water, or open water covered by a thin layer of ice. The lighter blue areas are cooler surfaces, such as thicker ice, according to NASA's Earth Observatory.

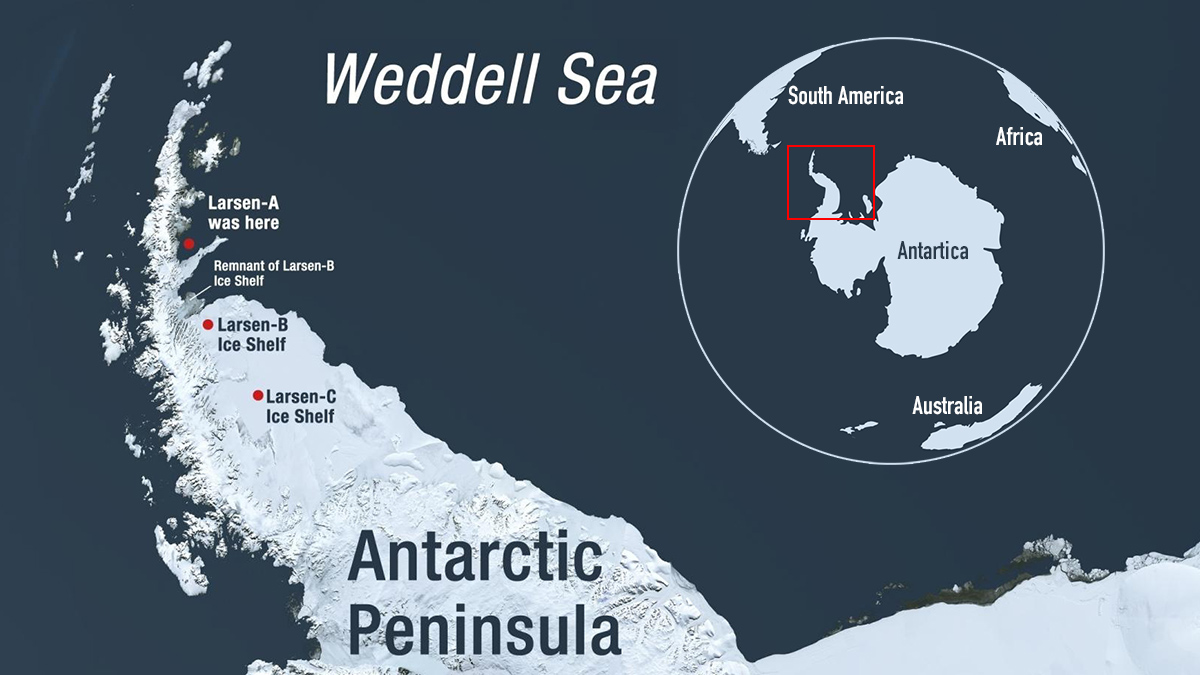

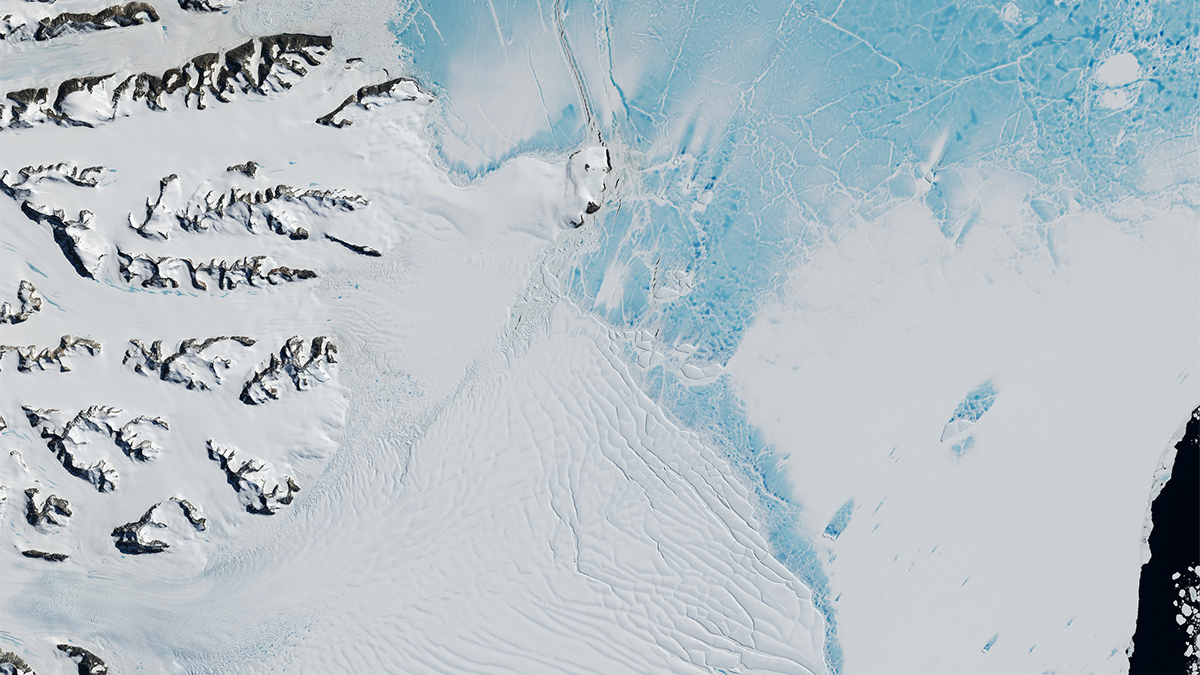

Losing mass

The Larsen ice shelf sits along the northeast coast of the Antarctic peninsula. Since 1995, it has lost 75 percent of its mass.

September issue

On Sept. 29, 2016, when this image was captured, the rift in the Larsen C ice shelf had grown to 80 miles (130 km).

Post calving

Another image of the Larsen C rift from Nov. 10, 2016. Once Larsen C calves an iceberg, scientists are concerned the ice shelf will begin to retreat. "Iceberg calving is a normal part of the glacier life cycle, and there is every chance that Larsen C will remain stable and this ice will regrow," Paul Holland, a BAS ice and ocean modeler, said in a statement. "However, it is also possible that this iceberg calving will leave Larsen C in an unstable configuration. If that happens, further iceberg calving could cause a retreat of Larsen C."

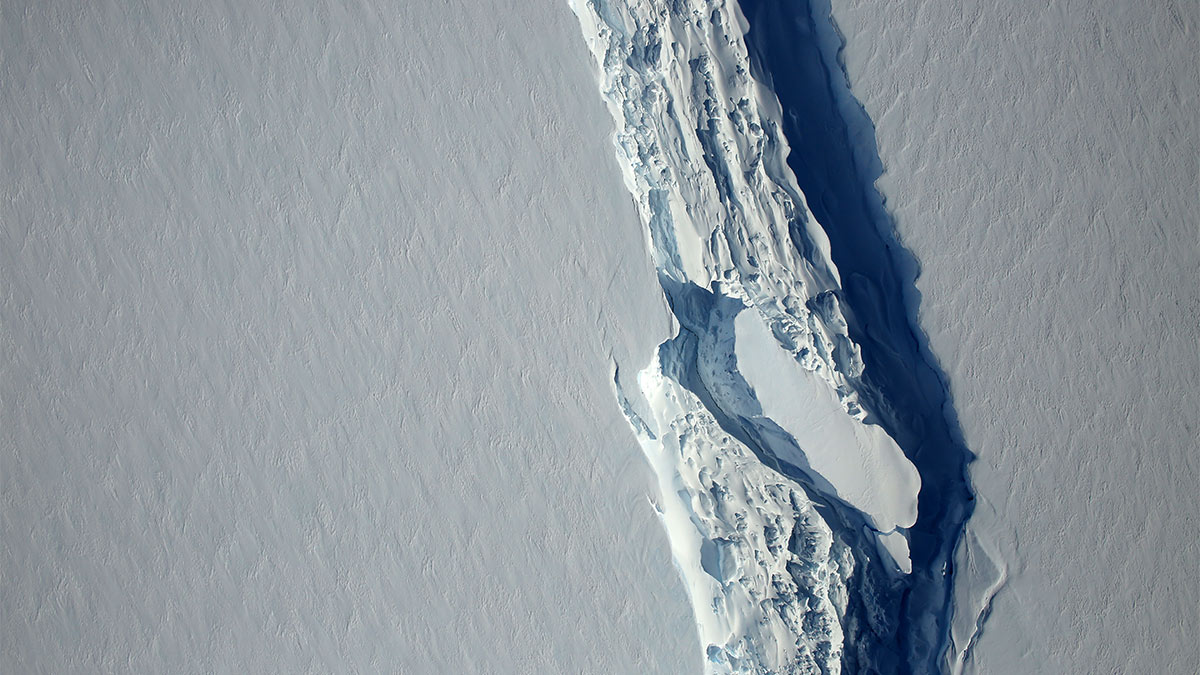

Gaping rift

The wider part of the rift in the Larsen C can be seen on Nov. 10, 2016, in this mosaic image created from multiple satellite snapshots.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Holding back the flood

Though the collapse of ice shelves doesn't directly contribute to sea-level rise, as the ice is already floating on the sea, they may indirectly result in a rising sea. For instance, when Larsen A and B calved icebergs, the result was a significant acceleration of the flow of land-based glaciers behind them; that led to more ice flowing into the ocean, and in turn, sea-level rise, according to the British Antarctic Survey.

Summer crack

The rift is visible in these images acquired on Aug. 22, 2016, with an imaging instrument aboard NASA's Terra satellite. The instrument has nine cameras pointing in different directions to give different perspectives of a landscape. This natural-color image relied on the instrument's downward-looking (nadir) camera. The ice shelf is visible on the left, and thinner sea ice appears on the right.

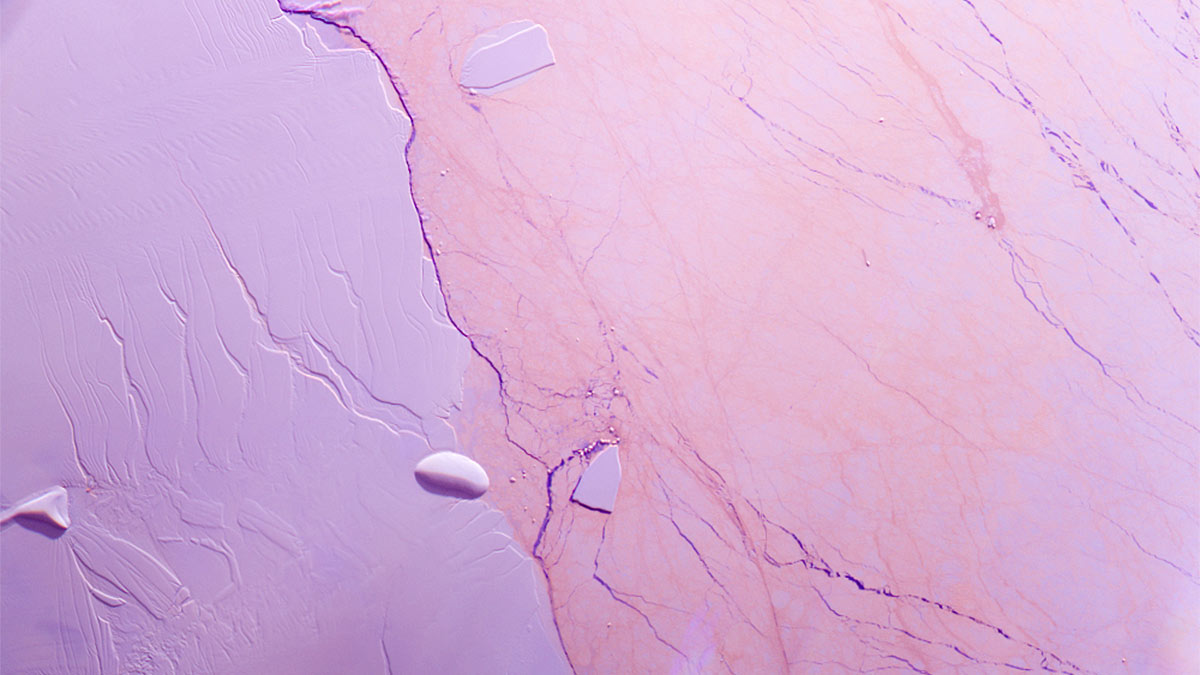

Different angles

Another image of the rift seen on Aug. 22, 2016, but from a different perspective; the composite image includes snapshots from the Terra satellite imager's backward-, vertical- and forward-pointing cameras. Rougher surfaces appear pink, while smoother areas are purple. Though sea ice is generally rougher than the ice shelf, the one exception is the shelf's rift; the rough texture of the rift indicates it is actively growing, scientists said. The crack grew 13 miles (22 kilometers) over the prior six months, and in August 2016, it extended some 80 miles (130 km).

Fast ice

The Antarctic peninsula, where the Larsen ice shelf resides, is one of the fastest-warming places on the planet. This mosaic image is centered on the northern part of the ice shelf. Comprising four natural-color images captured by the Operation Land Imager on the Landsat-8 satellite on Jan. 6 and Jan. 8, 2016, the mosaic shows the remaining ice of Larsen B and Larsen B. Light-blue areas represent sea ice anchored to the coastline or ice shelf (called fast ice) and covered in meltwater. White areas indicate fast ice covered by windblown snow.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.