Delaware-Size Iceberg Is About to Break Off of Antarctica

Antarctica's Larsen C ice sheet is flowing fast. In fact, researchers who are observing the unstable ice sheet have found that it is speeding up, indicating that a massive iceberg could break off, or calve, anytime now — it might be hours, days or weeks, they wrote in a new blog post at Project MIDAS.

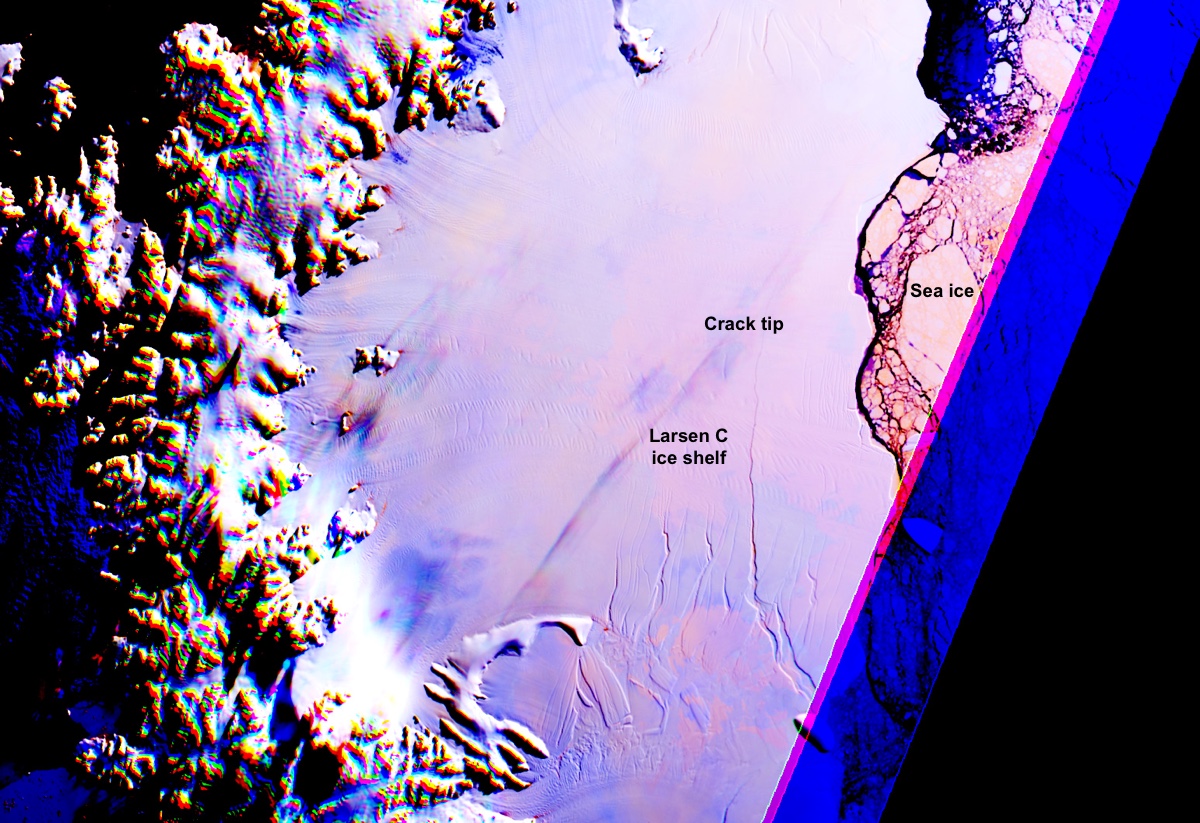

Project MIDAS is a United Kingdom-based project designed to observe Larsen C's dynamics as the climate warms. So far, the news is not good. Scientists have been tracking a growing rift in Larsen C since 2014. In early December 2016, the crack was 70 miles (112 km) long. Six weeks later, it was 109 miles (175 km) long and still growing. A new crack formed in May, while the main rift stabilized in length but continued to grow in width.

When the inevitable ice calving comes, the sheet will birth an iceberg approximately the size of Delaware, and will remove between 9 and 12 percent of Larsen C's total area. This could speed the dissolution of the shelf and remove some of the barrier that dams the land-based ice behind the floating ice shelf from the sea, according to Project MIDAS researchers. [See Images of Antarctica's Larsen C Ice Shelf and Rift]

The Larsen ice shelf, which is along the northeast coast of the Antarctic peninsula abutting the Weddell Sea, has already lost 75 percent of its mass since 1995, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center. That year, about 580 square miles (1,500 square kilometers) of the Larsen A portion of the sheet broke away. In 2002, 1,255 square miles (3,250 square km) of the Larsen B ice sheet calved off.

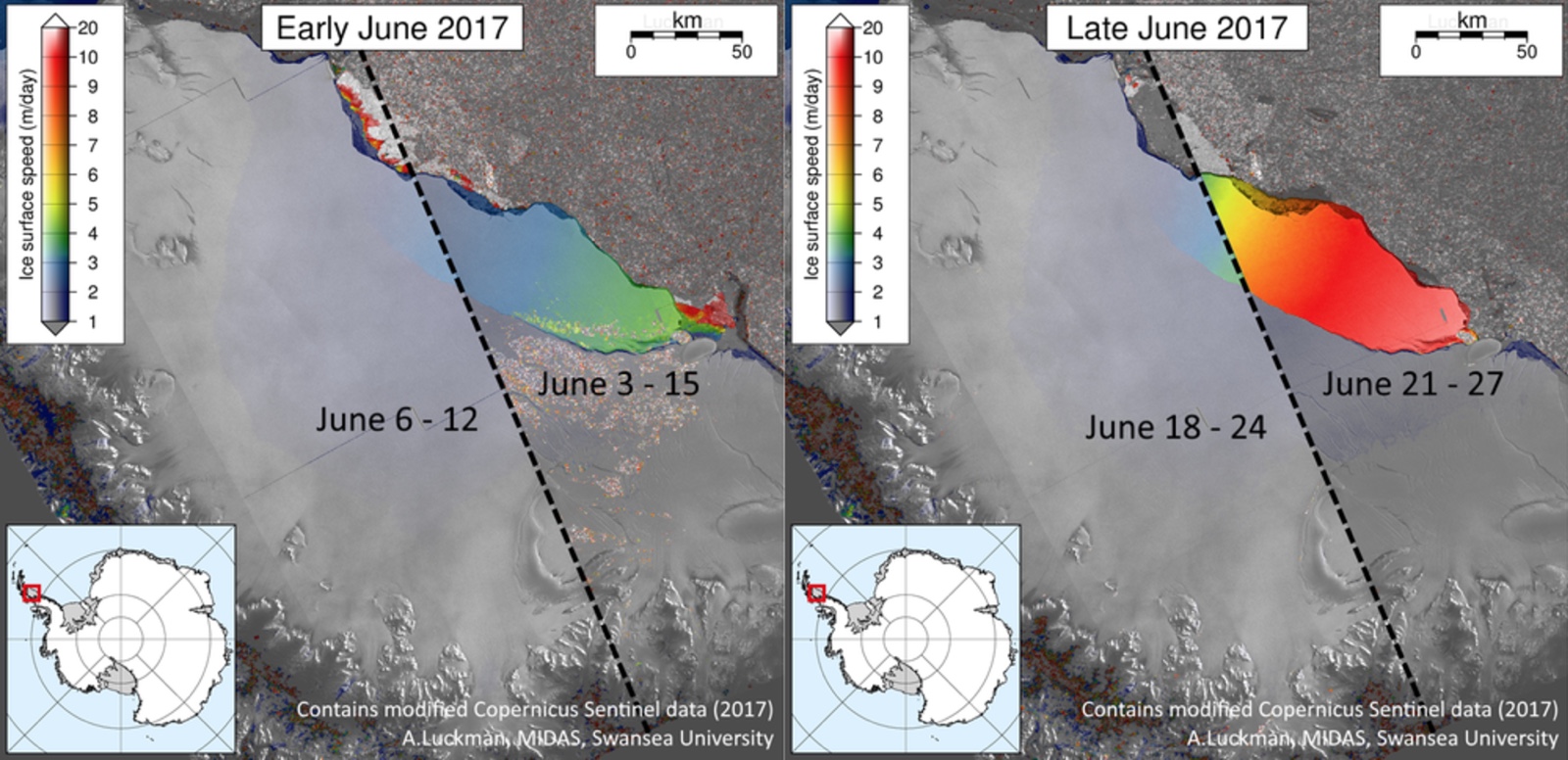

Now, Project MIDAS researchers have observed that the seaward side of the rift has tripled in speed and is now flowing 33 feet (10 m) per day as of June 24 through June 27.

"The iceberg remains attached to the ice shelf, but its outer end is moving at the highest speed ever recorded on this ice shelf," the researchers wrote.

The speed observations don't show the tip of the rift, but an image taken by the Sentinel-1 satellite on June 28 shows that the ice is still precariously attached to the main ice sheet, the researchers added. The team has found that, after the calving event, Larsen C likely will be less stable and more prone to a total collapse.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.