What Were the First Records of Solar Eclipses?

Got your eclipse glasses? People across the United States are counting the days to the arrival of this year's much-anticipated total solar eclipse on Aug. 21.

This year marks the rare occasion when viewers across the entire U.S. will experience totality — the sun's path while it is completely blocked by the moon's shadow. It will be the first total eclipse in nearly 40 years to be visible from the continental U.S., and the first in 99 years with the path of totality traveling from coast to coast in the U.S., from Oregon to South Carolina.

But total solar eclipses themselves are not uncommon, occurring about every 18 months, on average. (Solar eclipses of any kind occur about two to five times a year, on average.) And while 2017 sees many gripped by "eclipse fever" for the first time, people have been observing, documenting and describing eclipses for thousands of years. [The 8 Most Famous Solar Eclipses in History]

The first recorded notation referencing an eclipse dates to about 5,000 years ago, according to NASA. Spiral petroglyphs carved on three ancient stone monuments in Ireland at Loughcrew in County Meath, depict alignments of the sun, moon and horizon, and likely represent a solar eclipse that occurred Nov. 30, 3340 B.C., NASA reported.

Irish paleoarchaeologist Paul Griffin suspected that the Neolithic petroglyphs referred to an eclipse, and began investigating them in 1999. Griffin confirmed the eclipse date in 2002 by using the Digital Universe astronomy software to calculate the alignment, which produced a late afternoon eclipse that obscured nearly the entire sun, he wrote in 2002 on the Syzygy Research and Technology website. On the Loughcrew monuments, multiple carvings show dozens of astronomical events, with overlapping concentric circles representing the solar eclipse, and isolated concentric circles indicating a lunar eclipse, according to Griffin.

Nearby, a gruesome find suggested that Neolithic interpretation of the eclipse may have included superstitious fears allayed by human sacrifice. A basin held burned bones from about 48 people, hinting that the eclipse may have been accompanied by a murderous ritual "to 'save' the Neolithic 'sky God' (Sun) from dying as it descended to the 'underworld' at the horizon," Griffin wrote in 2002.

"Made night from mid-day"

Other physical records of eclipses persist in carvings on 2,500-year-old clay tablets from ancient Babylonia, one of which described a total solar eclipse seen in the port city of Ugarit in what is now Syria, on May 3, 1375 B.C., according to NASA.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Descriptions of eclipses also appear in records from ancient China, with imperial astronomers reporting eclipses that occurred from the eighth century B.C. to the 15th century A.D., according to a study published in 2005 in the journal Archive for History of Exact Sciences.

In fact, historic records from China inscribed by imperial astronomers include references to 938 solar eclipses dating from the Chunqiu period (771 B.C. to 476 B.C.) to the start of the Ming Dynasty (A.D. 1368 to 1644), of which only a handful have been found to be errors or false reports, the study author reported.

Writings from the ancient Greeks also described solar eclipses, with the lyric poet Archilochus, who lived during the seventh century B.C., commemorating what may have been a total solar eclipse that occurred on April 6, 647 B.C., writing, "Zeus, father of the Olympians, made night from mid-day, hiding the light of the shining Sun, and sore fear came upon men," according to NASA.

Photos, or it didn't happen

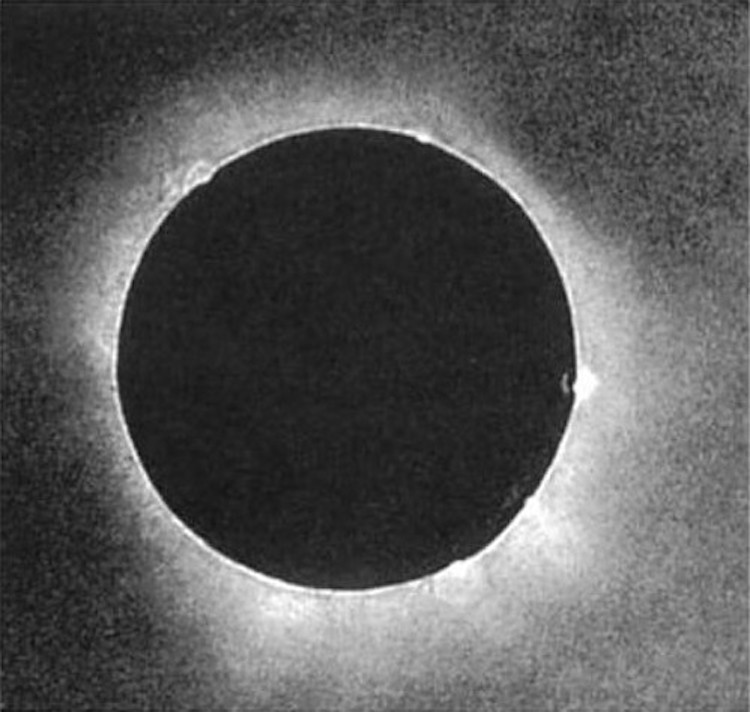

For thousands of years, written descriptions etched on stone and bone, and artists' interpretations of eclipses were the only means of recording this incredible cosmic event. But in the mid-19th century, an early form of photography known as daguerreotype enabled Johann Julius Friedrich Berkowski to create the first photographic record of a solar eclipse, on July 28, 1851.

Berkowski captured the image — the first to accurately represent the solar corona — in Königsberg in what was then the Roman Empire, now Kaliningrad in Russia. He used a small refracting telescope with a diameter of 2.4 inches (6.1 centimeters) and exposed the daguerreotype plate for 84 seconds, beginning soon after the sun was completely obscured, according to a study published in 2005 in the journal Acta Historica Astronomiae.

Since then, astrophotographers have plied their lenses to capture increasingly detailed views of this cosmic phenomenon, from time-lapse video of a total solar eclipse over Europe on March 20, 2015, caught by the European Space Agency's Proba-2 satellite, to a stunning "double eclipse" imaged by the Solar Dynamics Observatory on Sept. 1, 2016, when the sun was shadowed simultaneously by both the Earth and the moon.

Photos taken in 2013 by the Curiosity rover on Mars even offered a view of an eclipse as seen from another planet, as the Martian moon Phobos traveled across the sun.

Want some tips for creating your own spectacular photographic record of the Aug. 21 total eclipse? Check out these suggestions from our sister site, Space.com.

REMEMBER: Looking directly at the sun, even when it is partially covered by the moon, can cause serious eye damage or blindness. NEVER look at a partial solar eclipse without proper eye protection. Our sister site Space.com has a complete guide for how to view an eclipse safely.

Editor's Note: This article was updated to correct a statement about the frequency of total solar eclipses, which occur about every 18 months, not two to five times a year as had been stated.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.