Centuries of Tradition: Stunning Photos of Native American Hopi Pottery

Beauty from the earth

Across the earth, nature has created limitless examples of magnificence in the natural designs of both plants and animals, as well as the splendor of the world's many spectacular landscapes. And every once in a while, new forms of beauty are also found when the creative hands of humans lovingly interact with the natural elements of the world.

Impressive example

One such example of the expressive interaction between items found in the natural world and man has been found for hundreds of years in the southwestern deserts of the United States, where Native American potters have searched for the finest of clay soils and fashioned that clay into meaningful, useful and beautiful ceramic items.

Hopi potters

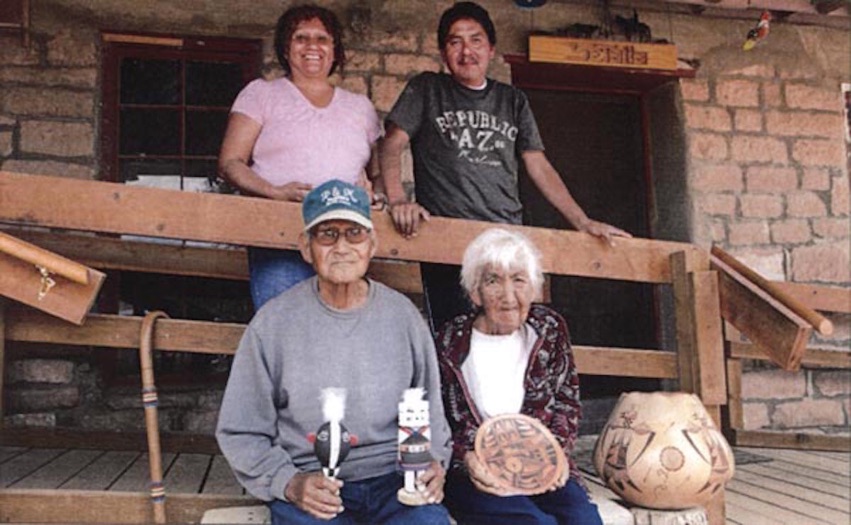

Two such Hopi potters, Gwen and Dee Setalla, are brother and sister of the Frog Woman/Feather Women Potters who are historically known for their White Slip polychrome pottery. They are descendants of two generations of Hopi potters with their late mother, Pauline Setalla, being the most renowned. The Setallas follow in the tradition of Native American potters that archeologists tell us began some 7,500 years ago in the lower Amazon Basin of South America. The oldest known Hopi pottery is gray utility ware that dates back to 700 A.D. Pauline, her late husband Justin, Gwen and Dee Setalla are all shown here.

Generations of skill

The ancient Hopi potters passed their knowledge and skills on from one generation to the next. By the late 1800s, respect and appreciation for Hopi artists and their pottery began to spread across the world and the revival period of artistic Hopi pottery began. First Mesa, that ancestral home of the Setalla family, became best known for their spectacular pieces of pottery.

Color from nothing

The soil found across the Hopi Nation is predominately sedimentary, laid down during the geological periods when shallow seas ebbed and flowed over the entire region. Alluvial fans are common with many outcroppings of sandstone, shale, sandy loam and layers of yellowish-brown and light gray clay. Hopi clay when fired tends to change in color from cream to light red because the strata of clays found here are rich in iron.

Sacred places

Traditional Hopi potters still dig their clay from sacred holes found upon their ancestral land. The clay is usually found just a few inches under the hard, rocky top soils and tends to chip and fracture in small, flat grayish pieces. The Setallas say that one "must be very grateful for the clay and pottery." Prayers are said each morning with cornmeal and "when we dig clay, we leave food there. You can't be greedy and not leave anything."

Step by step

Once the sacred clay is removed from the earth, the potters take it through a series of steps to prepare it. All the processing is done by hand. Dee Setalla states that working with the clay is "like you are bringing it to life. You must treat it with respect. You treat it like you are raising a child, and guide it through the growing stages."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Shaping the pots

Hopi potters today still shape their pots with the techniques that their ancestors taught them. The coiling then scraping of the clay is the most common technique. Pottery wheels are never used by traditional Hopi potters. It is at this step of the pottery-making process that the potter's creative skills come into artful display.

Traditional decor

Traditional Hopi potters also paint their newly created pots in the ancient and traditional ways. Paints are made by boiling various local plants that have been collected each spring and which produce differing colors. The plants are boiled long enough to create a dark and thick "cake," which is known as guaco. The intricate and beautiful designs that are painted on the pots often reflect the potter's personal clan signs and symbols. Yucca leaf brushes are chewed and trimmed to various sizes for the potter to use while painting the designs freehand.

New fuel

Today's traditional Hopi potters fire their exquisitely decorated pots using sheep manure as the main source of fuel. Sheep are not indigenous to the Hopi people. They first arrived in the Hopi lands in 1629 when a group of Spanish Franciscan priests arrived at the First Mesa Hopi village of Awatovi to establish a mission church. Spanish sheep became a consistent source of food, their wool became a source of warm clothing and their dung a constant source of much-needed fuel to burn.

Rapid heating

Pots today are still fired in open-air kilns, covered with a heap of sheep dung and a few branches of cedar. The sheep dung provides a rapid and even heat when burned and can reach a temperature up to 2,300 degrees Fahrenheit (1,260 degrees Celsius). A typical sheep dung kiln will burn for approximately three to four hours.