Kinect Scans of T. Rex Skull Shed Light on Mysterious Holes

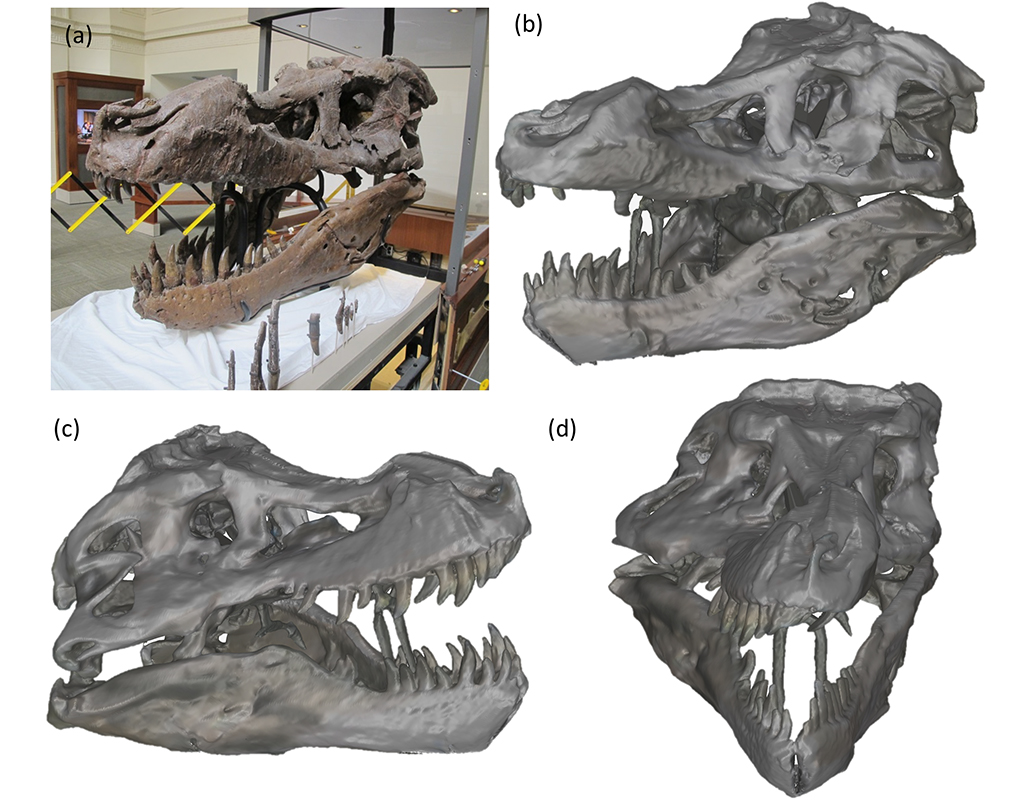

When a group of forensic dentistry experts set out in 2016 to investigate what may have caused some peculiar holes in a T. rex jaw, they decided to perform a 3D scan of the skull so they could examine the perforations more closely. But they ran into a big problem — the fossil skull was too massive to fit into existing 3D scanners.

However, the Camera Culture research team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Media Lab partnered with them to deliver those scans.

They did it with a consumer product designed for gesture recognition in gaming — the Microsoft Kinect — and used open-source software to capture and process the data, quickly creating 3D digital models of the T. rexfossil, a process the researchers described in a new study. [The 10 Weirdest Things Created By 3D Printing]

The skull belongs to one of the most complete — and most Twitter-famous — T. rex fossil skeletons in the world. Sue (@SUEtheTrex on Twitter) is housed at The Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH) in Chicago, measuring about 40.5 feet (12.3 meters) in length. Topping the skeleton is a replica of the dinosaur's skull; the real fossil weighs about 600 pounds (272 kilograms) and is displayed alone in a nearby exhibit case.

Odd punctures on Sue's lower jaw have long puzzled paleontologists. Some experts argued that they were caused by a predator's bite. Others suggested that a parasite bored holes in the jaw through the mouth's interior; this parasitic infection may have been so severe that it caused Sue to starve to death.

A 3D scan of the jaw would allow researchers to examine the holes more closely to figure out the culprit. The Kinect offered a unique solution to scanning such a large and heavy object — rather than muscle the fossil into a scanner, simply walk the scanner around it.

A Kinect interacts with objects in front of its camera lens by bombarding them with bursts of infrared light, which bounce back to a sensor. Built-in software takes that data and gauges the object's depth, constructing a 3D map of what the Kinect "saw."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

More important, a Kinect is light and portable and has a wide field of view — 70 degrees horizontal and 60 degrees vertical. A single user can carry it on a monopod or wear it on a special rig and walk around an object to create a 3D scan, which is exactly what the study's lead author Anshuman Dasdid, he said in a statement.

Das, a researcher with the Camera Culture group at MIT, said he completed a circuit around the skull in about 2 minutes, after plotting a course that navigated an irregularly shaped space and circumvented several obstacles that couldn't be moved. Other small sections of the jaw and skull were scanned separately, using a Kinect mounted on a monopod, the study authors reported.

The resulting 3D digital models called into question both hypotheses about the holes. Varying angles of the holes suggested that they couldn't have been produced by one bite. And the holes were narrower on the inside of the jaw, hinting that they originated on the outside, and were not created by parasites or bacteria working from the inside out.

An interactive model of Sue's skull is available online to download for free and examine in 3D space using Adobe Acrobat Reader, also available for free.

For now, the mystery about the holes remains unsolved. But the process for examining them has great promise for future work with fossils, the study authors wrote.

A Kinect scanning setup costs about $150, and the software is free. By comparison, industrial 3D-scanning systems can cost as much as $50,000 — and that doesn't include the cost of software, the researchers said. Their findings suggest that the Kinect could provide researchers, museum educators and others with an affordable means for 3D-scanning large fossils quickly and with a significant amount of detail, putting the technology within reach of those who couldn't formerly afford it, Das said in a statement.

"A lot of people will be able to start using this," he said.

The findings were published online Wednesday (July 5) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.