How Antarctica's Larsen C Ice Shelf Birthed Such an Enormous Berg

An enormous crack in Antarctica's Larsen C ice shelf that was steadily growing for months has finally given way. The event reduced the size of Larsen C by about 12 percent and dramatically changed the shape of the frozen continent, perhaps forever.

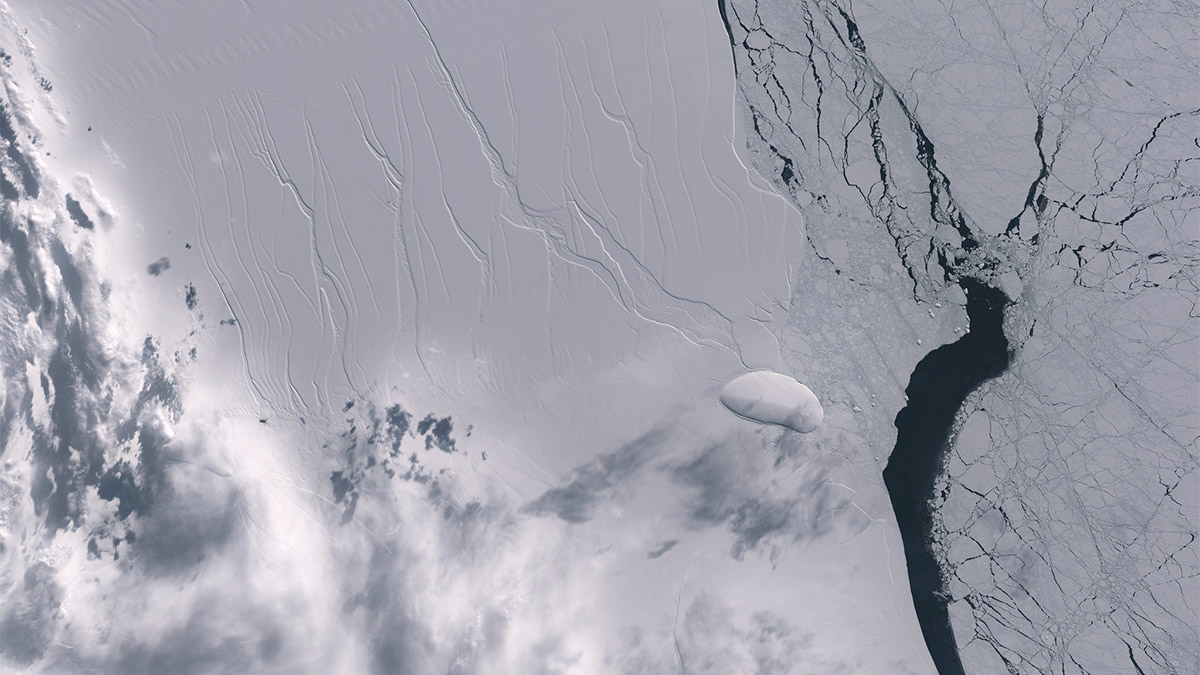

Between July 10 and today (July 12), a massive iceberg measuring approximately 2,240 square miles (5,800 square kilometers) — one of the biggest ever recorded — separated from Antarctica's western peninsula, the European Space Agency (ESA) reported.

The saga of this iceberg goes back years, with scientists and satellites alike diligently scrutinizing the crack that birthed the hunk of ice. [In Photos: Antarctica's Larsen C Ice Shelf Through Time]

Data from NASA's Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on the Aqua satellite revealed the break. The iceberg's separation was later confirmed by NASA's polar-orbiting Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) instrument, which captures imagery in visible and infrared, researchers with the British Antarctic research group Project MIDAS reported in a blog post.

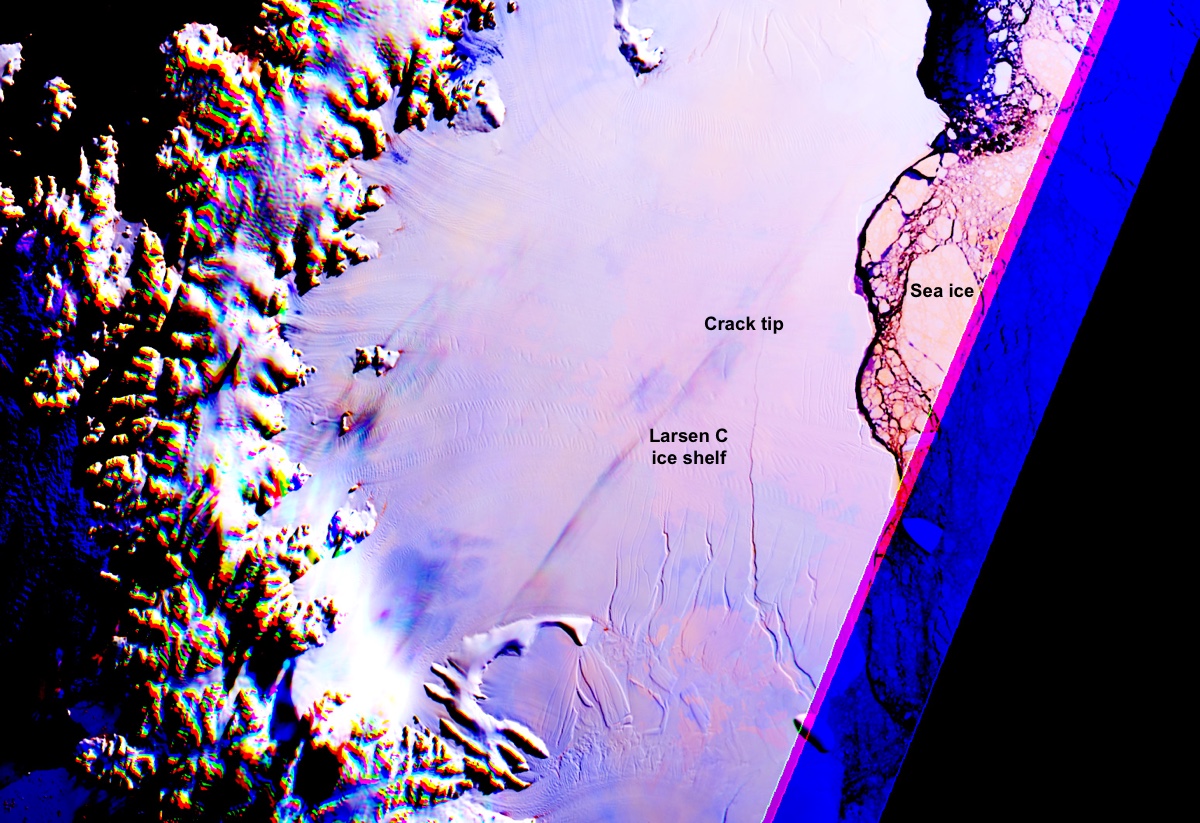

The Larsen C break was also evident in a photo captured July 12 by Copernicus Sentinel-1, an ESA satellite that uses radar to scan and capture images of Earth's surface in order to monitor the effects of human activity and climate change.

MODIS scientists had been using Sentinal-1 data to monitor the progress of the Larsen C crack, relying on the satellite's radar technology to capture images even during the dark of winter in the Southern Hemisphere, ESA representatives said in a statement.

This is the third ice shelf on the western peninsula of Antarctica to undergo massive ice loss in just over two decades. The Larsen A ice shelf broke apart in 1995, and between Jan. 31 and March 7, 2002, Antarctica lost 1,250 square miles (3,250 square km) of ice when the Larsen B shelf collapsed, according to NASA.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ice shelves take shape as advancing glaciers and ice sheets flow from land to the coastline and extend over the sea. These giant structures can build up over many thousands of years, but persistently warmer-than-average air and ocean temperatures are now bringing about the shelves' disintegration in a matter of months, researchers have said.

Because ice shelves are platforms already floating on the ocean's surface, they don't immediately contribute to sea-level rise when they collapse, according to the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSICD). But once the ice shelf is weakened or in pieces, it can no longer hold back the glaciers moving toward the sea, and this can dramatically increase the amount of ice and water pouring directly into the ocean, NSIDC reported.

And while the Larsen C ice shelf will begin to rebuild itself, it won't be as stable as it was before the collapse, MIDAS researchers said in a statement.

Countdown to collapse

Average ocean temperatures in Antarctica have been rising since the 1990s, especially around the peninsula where Larsen C is located. Scientists reported in 2015 that Larsen C was riding lower in the water than it had previously and had lost 13 feet (4 meters) of ice that could not be attributed entirely to warming air temperatures.

The first signs of a northward-extending crack in Larsen C appeared in 2010 and progressed in 2014, according to a study published in 2015 in the journal The Cryosphere.

Then, a photo of a massive crack in Larsen C was captured on Nov. 10, 2016, by researchers with NASA's Operation IceBridge, a survey of polar ice from the air. At that time, the rift measured approximately 70 miles (113 km) long and 300 feet (91 m) wide. IceBridge experts warned that if the crack extended far enough for an iceberg to separate from Larsen C, the iceberg would be approximately the size of the state of Delaware.

By Jan. 19, 2017, the crack had extended to 109 miles (175 km) in length and 1,500 feet (460 m) in width. This left the shelf's edge precariously connected to the mainland part by a frozen expanse measuring only 12.4 miles (20 km) long.

A second crack, measuring about 6 miles (9.7 km) long, appeared in May 2017, branching away from the original rift and further weakening the Larsen C shelf. Researchers warned that this crack could hasten the shelf's collapse.

On June 28, MIDAS researchers reported that the Larsen C ice sheet was flowing faster than ever — advancing 33 feet (10 m) each day, "the highest speed ever recorded on this ice shelf," the scientists wrote in a blog post. This hinted that a collapse was perhaps only hours away, they wrote.

The iceberg-to-be was barely hanging on by July 6, with the crack measuring 124 miles (200 km) long and a mere 3 miles (5 km) of ice connecting the future iceberg to the ice shelf. New cracks were extending from the end of the main rift. Then, on July 12, the enormous iceberg — holding a volume of frozen water about twice that contained in Lake Erie — finally broke free, MIDAS researchers reported.

While scientists knew that the Larsen C iceberg's separation was imminent, the speed at which it advanced was unexpected, Adrian Luckman, a professor of glaciology at Swansea University in the United Kingdom and a MIDAS project leader, said in a statement.

And it is yet to be seen what far-reaching effects the swift loss of so much ice will have, he added.

"We have been expecting this for months, but the rapidity of the final rift advance was still a bit of a surprise. We will continue to monitor both the impact of this calving event on the Larsen C ice shelf and the fate of this huge iceberg," Luckman said.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.