Scientists will soon venture to the world's hidden eighth continent, the sunken land of Zealandia.

The lost continent, which is mostly submerged, with all of New Zealand and a few islands peeking out from the water, is about half the size of Australia. By drilling deep into its crust or upper layer, the new scientific expedition could provide clues about how the diving of one of Earth's plates beneath another, a process called subduction, fueled the growth of a volcano chain and this lost continent in the Pacific Ocean 50 million years ago. The new expedition could also reveal how that Earth-altering event changed ocean currents and the climate.

"We're looking at the best place in the world to understand how plate subduction initiates," expedition co-chief scientist Gerald Dickens, professor of Earth, environmental and planetary science at Rice University in Texas, said in a statement. "This expedition will answer a lot of questions about Zealandia." [The 10 Biggest Earthquakes in History]

The lost continent

In February, scientists argued in the journal GSA Today that Earth has a hidden eighth continent, which should be reflected on maps.

The argument for Zealandia being a continent was based on several lines of evidence. Rocks beneath the ocean floor off New Zealand's coast are made up of a variety of ancient rock types that are found only on continents, not in oceanic crust. The continental shelves of Zealandia are much shallower than those of the nearby oceanic crust. And, rock samples reveal a thin strip of oceanic crust separating Australia and the underwater portions of Zealandia. All of these factors suggest the area underwater around New Zealand makes up a continent, the researchers reported.

Journey to the eighth continent

However, there are still some questions about how Zealandia formed.

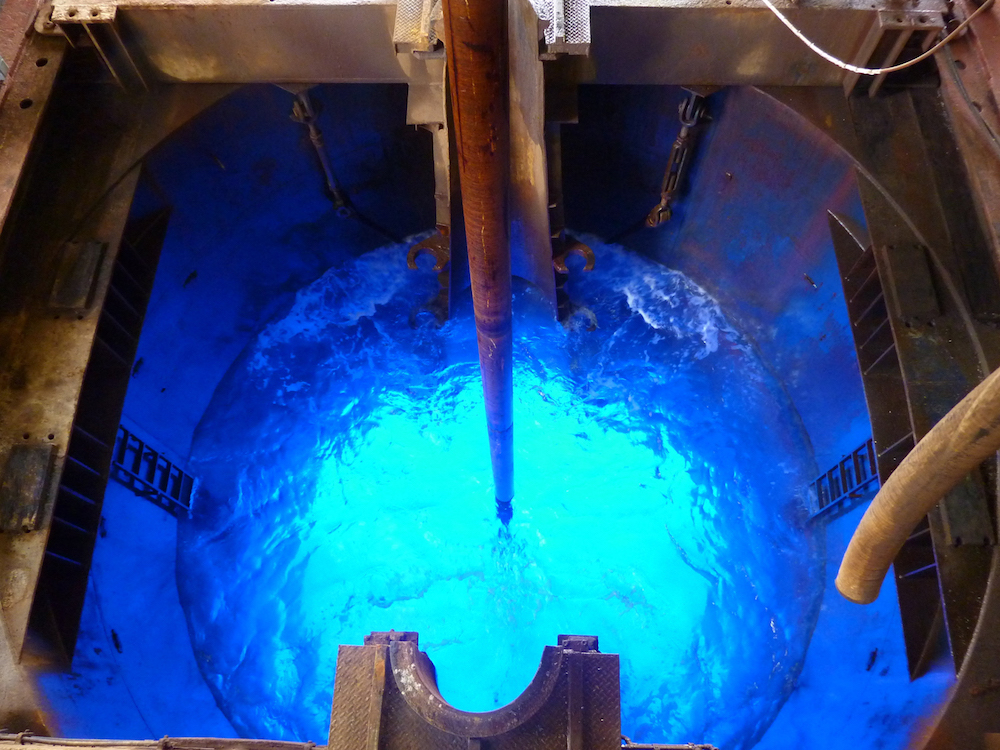

Expedition 371, which is funded by the National Science Foundation and the International Ocean Discovery Program, aims to answer many of those questions. More than 30 scientists will set sail on July 27 for a two-month expedition aboard the JOIDES Resolution, a massive scientific drilling ship.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

From there, the team will visit six sites in the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand to drill cores of sediment and rocks from the Earth's crust. Each core will be between 1,000 feet and 2,600 feet (300 meters and 800 meters), meaning that scientists can peer back in time over tens of millions of years.

"If you go way back, about 100 million years ago, Antarctica, Australia and Zealandia were all one continent," Dickens said. "Around 85 million years ago, Zealandia split off on its own, and for a time, the seafloor between it and Australia was spreading on either side of an ocean ridge that separated the two."

After this shift, the area between the two continents was compressed. But around 50 million years ago, the Pacific Plate dove beneath New Zealand, lifting up the two islands, forming a string of volcanoes in the Pacific, and relieving the compressive stress in the ocean crust between the two continents.

"What we want to understand is why and when the various stages from extension to relaxation occurred," Dickens said.

The new findings could reveal how ocean currents and climate changed at the time. Zealandia is usually left out of most climate models dating to 50 million years ago, which could explain why those models have been problematic, Dickens said.

"It may be because we had continents that were much shallower than we had thought," Dickens said. "Or we could have the continents right but at the wrong latitude. Either way, the cores will help us figure that out."

Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.