Unusual Phobia: Researchers Suggest New Reason for Fear of Bubbles

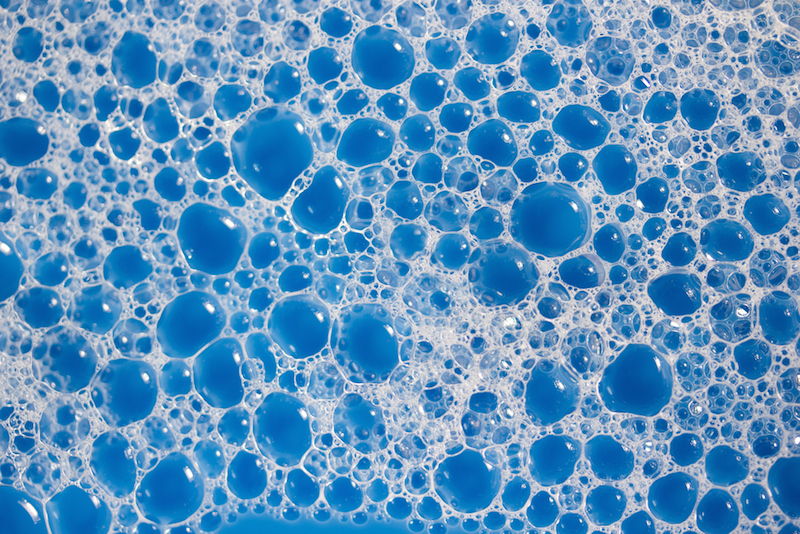

Some people are so afraid of snakes or spiders that the sight of these creatures makes their hearts race, their breathing speed up and their palms sweat. But other people have similarly uncontrollable reactions to seeing clusters of bubbles. Their skin begins to crawl, they become nauseated and they may even throw up.

Why clusters of bubbles — or circles or holes — that pose no threat can elicit such strong feelings of disgust has been discussed since the condition, called trypophobia (which means "fear of holes" in Greek), was first documented in 2013. Some scientists have suggested that the extreme reaction to round shapes occurs because they resemble spots or circles found on poisonous animals, including snakes and the blue-ringed octopus.

But now, new research suggests that the intense anxiety is likely linked to fears of parasites and infectious diseases. Diseases, including smallpox and measles, as well as parasites, like mites and ticks, produce patterns on the skin that look like clusters of round shapes. [What Really Scares People: Top 10 Phobias]

"Pathogens and parasites have been one of the main threats to humans and animals during their evolutionary history," said Tom Kupfer, a postgraduate researcher in psychology at the University of Kent in England. Avoiding them reduces the chance of getting sick, he told Live Science.

"It's fairly well recognized that the most significant adaption humans have for disease avoidance is the emotion disgust," Kupfer said.

To investigate whether the disgust reaction in people with trypophobia was a "disease avoidance" tactic, Kupfer and his co-author An Trong Dinh Le, who was a PhD candidate in psychology at the University of Essex at the time of the research, set up an experiment that involved tapping two Facebook support groups for people who describe themselves as having trypophobia.

The researchers recruited 300 people from the Facebook groups and 300 university students who did not have trypophobia. Both groups were shown a total 32 images. Eight photos contained so-called disease-relevant images of clusters linked to disease — for example, a rash of circles, a person's smallpox scars or a collection of blood-engorged ticks. Eight other photos contained disease-irrelevant images of harmless items that had clusters of circles, including drilled holes in a brick wall and a lotus flower seed pod. The other 16 photos had no holes, bumps or circular patterns at all.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Kupfer said he and Le predicted that both groups would find the disease-relevant images unpleasant but that only the people with trypophobia would also find the disease-irrelevant photos unpleasant. The researchers also predicted that most of the people would express feeling disgusted, not fearful. [9 DIY Ways to Improve Your Mental Health]

That's precisely what happened.

"We found that only a small percentage of them reported fear or fear-related feelings," Kupfer said. "The majority reported disgust or disgust-related feelings." The findings were published online July 7 in the journal Cognition and Emotion.

The researchers reported that when the people with trypophobia looked at images with clusters of holes or bubbles, they said things like, "The primary feeling is one of inexplicable and extreme revulsion," and "I feel disturbed in general and contaminated."

Kupfer said many people also reported feeling itchy and as though their skin were crawling. One person said, "I feel like the holes are all over my arms, legs and entire body, so I scratch my skin until it usually bleeds."

These comments related to skin sensations may indicate an extreme anxiety about parasites, the researchers concluded.

Kupfer noted that because this phobia is newly discovered, it hasn't been officially recognized as a mental disorder in the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

He would like to undertake a large-scale, comprehensive analysis to estimate how many people have it.

"Understanding it and describing it — its features and why it exists — is probably useful for the people who have it and the people who are going to try to treat it," Kupfer said.

Originally published on Live Science.