Sour Note: In Ancient Rome, Lemons Were Only for the Rich

Lemons were the acai bowls of the ancient Romans — prized by the privileged because they were rare, and treasured for their healing powers. In fact, this coveted fruit, as well as the citron, were the only citrus fruits known in the ancient Mediterranean — it took centuries for other fruits, such as oranges, limes and pomelos to spread westward from their native Southeast Asia, a new study finds.

However, the citrus fruits that followed in later years weren't as exclusive as lemons and citrons, said the study's lead researcher, Dafna Langgut, an archaeobotanist at Tel Aviv University in Israel.

"All other citrus fruits most probably spread more than a millennium later, and for economic reasons," Langgut, told Live Science in an email. [10 Biggest Historical Mysteries That Will Probably Never Be Solved]

Studying the ancient citrus trade took a lot of work. Langgut examined ancient texts, art and artifacts, such as murals and coins. She also dug into previous studies to learn about the identities and locations of fossil pollen grains, charcoals, seeds and other fruit remains.

Gathering this information "enabled me to reveal the spread of citrus from Southeast Asia into the Mediterranean," Langgut said.

Citrus trade

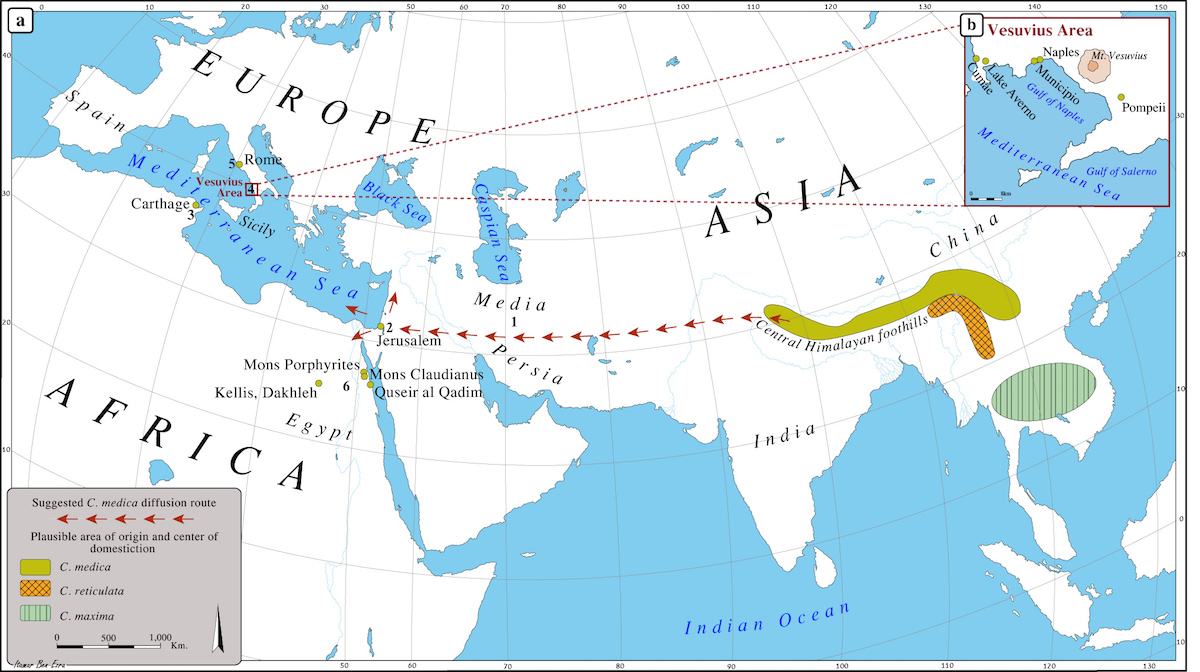

The citron (Citrus medica) was the first citrus fruit to reach the Mediterranean, "which is why the whole group of fruits is named after one of its less economically important members," she said.

The citron spread west, likely through Persia (remains of a citron were found in a 2,500-year-old Persian garden near Jerusalem) and the Southern Levant, which today includes Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, southern Syria and Cyprus. Later, during the third and second centuries B.C., it spread to the western Mediterranean, Langgut found. The earliest lemon remains found in Rome were discovered in the Roman Forum, and date to between the late first century B.C. and the early first century A.D., she said. Citron seeds and pollen were also found in gardens owned by the wealthy in the Mount Vesuvius area and Rome, she added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It took another 400 years for the lemon (Citruslimon) to reach the Mediterranean area. Lemons, too, were owned by the elite class. "This means that for more than a millennium, citron and lemon were the only citrus fruits known in the Mediterranean basin," Langgut said. (The Mediterranean basin would have included the countries around the sea.)

The upper crust of society likely viewed the citron and the lemon as prized commodities, likely "due to [their] healing qualities, symbolic use, pleasant odor and its rarity," as well as their culinary qualities, Langgut said.

The citrus fruits that followed were more likely grown as cash crops, she said. At the beginning of the 10th century A.D., the sour orange (Citrus aurantium), lime (Citrus aurantifolia) and pomelo (Citrus maxima) made it to the Mediterranean. These fruits were likely spread by Muslims through Sicily and the Iberian Peninsula, Langgut said.

"The Muslims played a crucial role in the dispersal of cultivated citrus in Northern Africa and Southern Europe, as evident also from the common names of many of the citrus types which were derived from Arabic," she said. "This was possible because they controlled extensive territory and commerce routes reaching from India to the Mediterranean."

The sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) traveled west even later — during the 15th century A.D. — likely via a trade route established by people from Genoa, Italy; the Portuguese established such a route during the 16th century, Langgut said.

Lastly, the mandarin (Citrus reticulata) made it to the Mediterranean in the 19th century, about 2,200 years after the citron first spread west, she said.

The study was published in the June issue of the journal HortScience.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.