Editor's Note: This story was updated on Aug. 2 at 5:00 p.m. E.T.

A group of scientists in Oregon has successfully modified the genes of embryos using CRISPR, a cut-and-paste gene-editing tool, in order to correct a genetic mutation known to cause a type of heart defect.

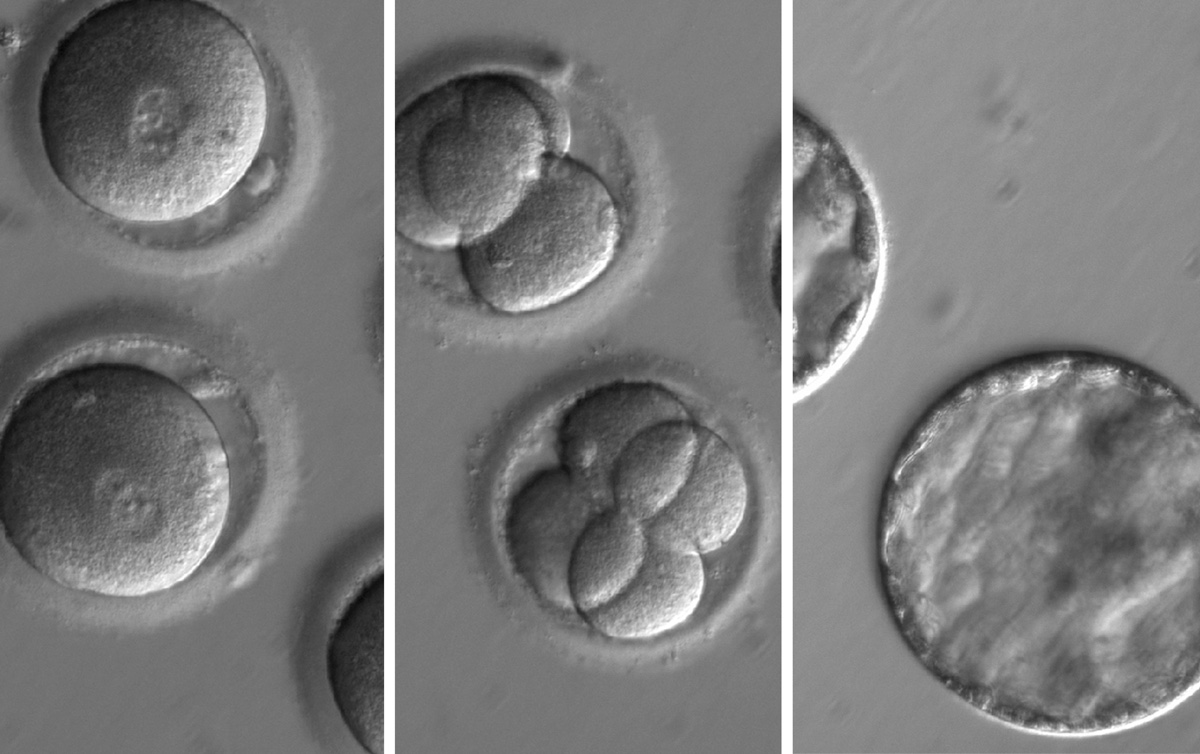

The experiments, which were described today (Aug. 2) in the journal Nature, were conducted by biologist Shoukhrat Mitalipov and colleagues at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. Mitalipov conducted the experiments on dozens of single-celled embryos, which were discarded before they could progress very far in development, MIT Technology Review reported last week when the results were initially leaked. This is the first time that scientists in the United States have used this approach to edit the genes of embryos.

Cut and replace

The CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing system is a simple "cut and replace" method for editing precise spots on the genome. CRISPRS are long stretches of DNA that are recognized by molecular "scissors" called Cas9; by inserting CRISPR DNA near target DNA, scientists can theoretically tell Cas9 to cut anywhere in the genome. Scientists can then swap a replacement gene sequence in the place of the snipped sequence. The replacement sequence then gets automatically incorporated into the genome by natural DNA repair mechanisms.

In 2015, a group in China used CRISPR to edit several human embryos that had severe defects, though none were allowed to gestate very long before being discarded. The Chinese technique led to genetic changes in some, but not all of the cells in the embryos, and CRISPR sometimes snipped out the wrong place in the DNA.

Major advance

The new results are a major advance compared with earlier efforts. In the new experiments, scientists eliminated the off-target effects of CRISPR/cas9.

The team used dozens of embryos that were created for in vitro fertilization (IVF), using the sperm of men who had a severe genetic defect. The sperm contained a single copy of the gene MYBPC3, which confers a risk of sudden death and heart failure due to thickening of the heart muscle known as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the new experiment, the team used Crispr/Cas9 to snip DNA at the location of the defective MYBPC3 gene in the fertilized eggs. Most of the embryos naturally repaired the break in the DNA by substituting the normal version of the gene, which originated in the egg. About two-thirds of the embryos did not contain the mutated version of the gene; and the team also eliminated the risk that some, but not all, of the cells in the embryos contained the edited genes.

In general, editing the germ line — meaning sperm, eggs or embryos — has been controversial, because it means permanently changing the DNA that is passed on from one generation to the next. Some scientists have called for a ban on germ-line editing, saying the approach is incredibly risky and ethically dubious.

However, a National Academy of Sciences report published earlier this year suggested that embryo editing could be ethical in the case of severe genetic diseases, assuming the risks could be mitigated.

Originally published on Live Science.

Editor's Note: This story was updated to include additional information from the recently published journal article on the technique.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Flu: Facts about seasonal influenza and bird flu

What is hantavirus? The rare but deadly respiratory illness spread by rodents