New Sunfish Species Is 8 Feet Long and Looks Like a Giant Pancake

It's not every day that someone discovers a new species of 8-foot-long (2.4 meters) fish — much less one that looks like its body was a victim of some sort of bizarre copy-and-paste accident.

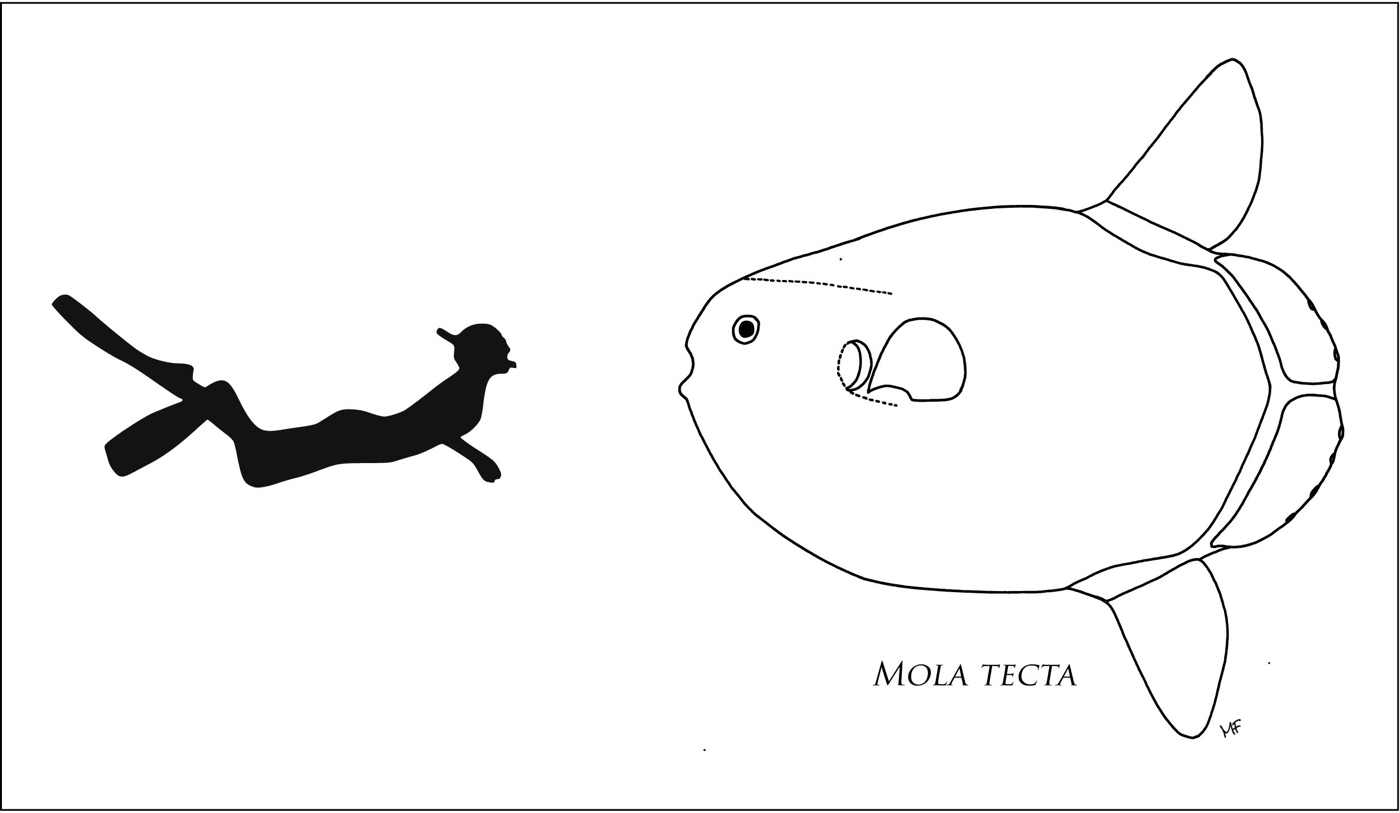

But new research reveals that an unknown species of huge, pancake-shaped sunfish has been hiding out in the oceans of the Southern Hemisphere. The fish, dubbed Mola tecta (which is Latin for "hidden"), is also known as the "hoodwinker" sunfish because scientists were unaware of its existence despite decades of research on these strange animals.

"Now that we have a good handle on the new species, it can no longer hoodwink us to nearly the same degree," Marianne Nyegaard, one of the fish's discoverers, wrote in an email to Live Science. [See Photos of This Weird Pancake-Shaped Fish]

Sunfish saga

Sunfish are enormous: As the world's largest bony fish, they can weigh up to about 2,200 lbs. (1,000 kilograms), a bulk they manage to maintain by scarfing down jellyfish by the boatload. They have extremely round bodies with strange, foreshortened ruffles on their back ends instead of true tails. (This body part is called a "clavus," which is Latin for "rudder," Nyegaard said.)

The precise number of sunfish species and their relationships to one another have long been difficult to pin down, in part because of the difficulties in transporting and storing a fish that can grow to be more than 8 feet long, Nyegaard and her colleagues wrote in a study published online July 19 in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society reporting the find. Genetic testing has helped to clarify; in fact, the researchers only discovered Mola tecta because a 2009 genetic study on sunfish tissue by Japanese researchers revealed gene sequences that didn't match those of any known species.

Nyegaard, too, ran across these mystery genes while analyzing tissue samples from sunfish that were accidentally hooked (and then thrown back) by commercial fishers.

"I still didn't know what the fish looked like, as I only received tiny skin samples from the fisheries observers," she said. "But now that I knew where the sample had come from, the hunt was on."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Searching for sunfish

The hunt was on, but it wasn't exactly clear how to find an elusive ocean fish with "literally no budget," Nyegaard said. Fortunately, a break came when three sunfish stranded themselves on a beach in Christchurch, New Zealand. Nyegaard couldn't get to New Zealand from Perth, Australia, where she works at Murdoch University, in time to sample the fish, but a "kind local" went out and collected tissue for her, she said. Just 10 days later, another specimen washed ashore at the same beach. This time, she hopped on a plane, arriving just before dark. [Photos: The Freakiest-Looking Fish]

"I got out and just stood there, under the stars with the ocean rolling in and the huge fish just lying there on the beach — a stranded, lost behemoth, both sad- and lonely-looking but also beautiful in the weirdest way, like a precious gift from the sea, a long-kept secret," she said.

She knew she had her mystery fish. The new species has a distinctive stripe of skin dividing its body from its clavus. It also has fewer bony formations called ossicles on its clavus than other sunfish species, Nyegaard said, and it has a rounded, rather than protruding, snout.

Nyegaard and her colleagues shored up their analysis with studies of old museum specimens as well as more fishery bycatch. M. tecta lives in the waters around southeastern Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and perhaps Chile, they found. Because these sunfish are so elusive, little is known about whether they are in danger of extinction, Nyegaard said. The International Union for Conservation of Nature has designated one other sunfish species, Mola mola, as "vulnerable."

Likely the biggest threats to the fish are climate change and warming oceans, Nyegaard said. Like all marine wildlife, she added, sunfish are threatened by plastic pollution in the oceans. Reducing plastic use, she said, could be one way to ensure these huge fishy pancakes keep swimming.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.