Rare Conjoined Bat Twins Found in Brazil

When Marcelo Rodrigues Nogueira, a postdoctoral researcher in biology at the State University of Northern Rio de Janeiro first saw the bat twins, he was "completely astonished," he wrote in an email to Live Science. "I have handled many bats [in my career], some with very impressive morphological characters (and bats are very special in this respect!), but none [were as] surprising as these twins." [See Photos of the Rare Conjoined Bats Found in Brazil]

Only two other pairs of conjoined bat twins have been reported in the scientific literature, one in 1969 and another in 2015.

Although it's not known exactly what causes identical twins to be conjoined, the phenomenon is known to occur when a fertilized egg splits too late. If an egg splits four to five days after being fertilized, two separate identical twins will form. If, however, the splitting doesn't occur until 13 to 15 days after fertilization, the fertilized egg will only separate partially, and the twins will be conjoined.

The researchers first became aware of the conjoined bats after the animals were donated to the Laboratory of Mastozoology at the Rural Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. No one from Nogueira's team, which includes embryologists Nadja Lima Pinheiro and Adriana Ventura from the Area of Embryology at the Rural Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, saw the twins right when they were found. Because of this, the scientists, aren't certain if the twins were stillborn or if they had died shortly after birth.

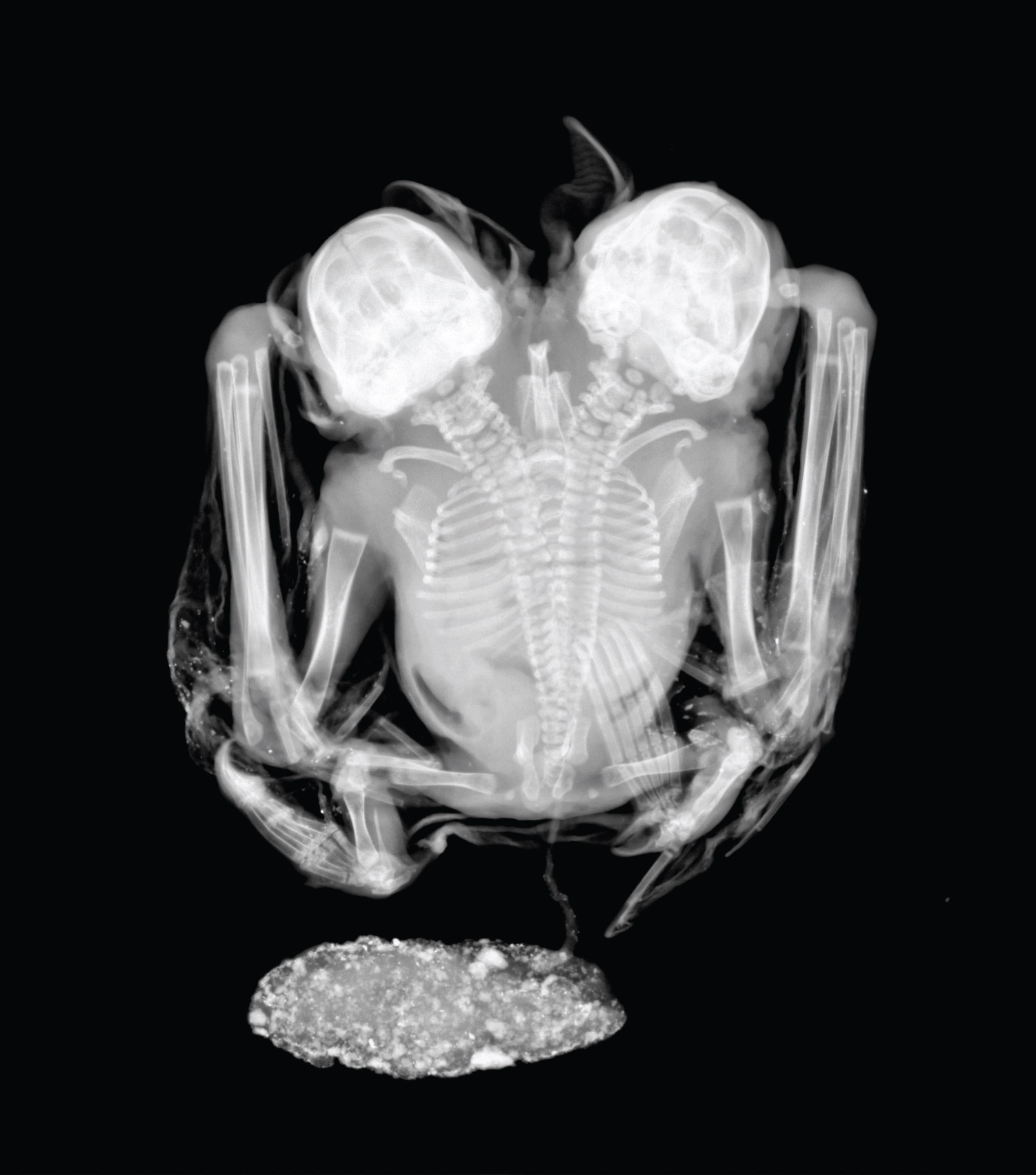

The bats, found under a mango tree in southeastern Brazil in 2001, are dicephalic parapagus conjoined twins, which means they're oriented side by side with their whole trunks conjoined. X-rays revealed that the twins' spines form a "Y" shape, with two separate columns of vertebrae branching off at the lower back. Ultrasound images also revealed two hearts of equal size that researchers suspect are separate, the scientists said.

Since most bats have only one pup per litter, finding even nonconjoined bat twins is rare. In the five years Daniel Urban, a postdoctoral research associate in evolutionary developmental biology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, has been studying bats, he's only ever seen a single pup flying around or hanging onto its mother, he told Live Science. Urban was the lead author of the 2015 study on conjoined bat twins that was published in the journal Acta Chiropterologica.

It's even harder to find bat twins that are conjoined. But this doesn't mean conjoined twins are rarer in bats than in any other mammals, according to Scott Pedersen, a professor of biology and microbiology at South Dakota State University, who was not involved in the new study. It's just that humans find out about conjoined bats less often than they find out about other conjoined animals, he told Live Science in an email. [Image Gallery: Evolution's Most Extreme Mammals]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Even if conjoined bats are alive when they are born, it's likely that they'll die soon after, because their bodies can't sustain them, Pedersen said. Bats also tend to live in places humans aren't located, which means even if a person were to venture into a bat's domain, the person would need to find the conjoined bats before they degraded or were scavenged.

This is only made more unlikely by the fact that bats are nocturnal, said Urban. If a mother gives birth to conjoined bats during the day, it will likely be in a protected roost, which means people wouldn't see them. She may give birth while she's out in the open, but that would occur only at night, when the twins would be obscured by darkness, Urban said.

"If you combine all these factors together, it's amazing we even have any [conjoined bat twins]," he added.

Although little is known about the organs of the recently discovered conjoined bat twins, the researchers have opted not to use any invasive methods to further investigate the animals' bodies.

"It's so rare and precious that you find something like this, you don't want to do any type of destructive sampling to look further. You're, of course, very curious about it, but they're a one-shot deal so, for the most part, they're held onto until the future where a newer technology will allow us to pursue it further without completely damaging what we already have," Urban said.

The new study was published online June 16 in the journal Anatomia Histologia Embryologia.

Original article on Live Science.