These Stunning 3D Images Reveal How a Massive Greenland Glacier Has Changed

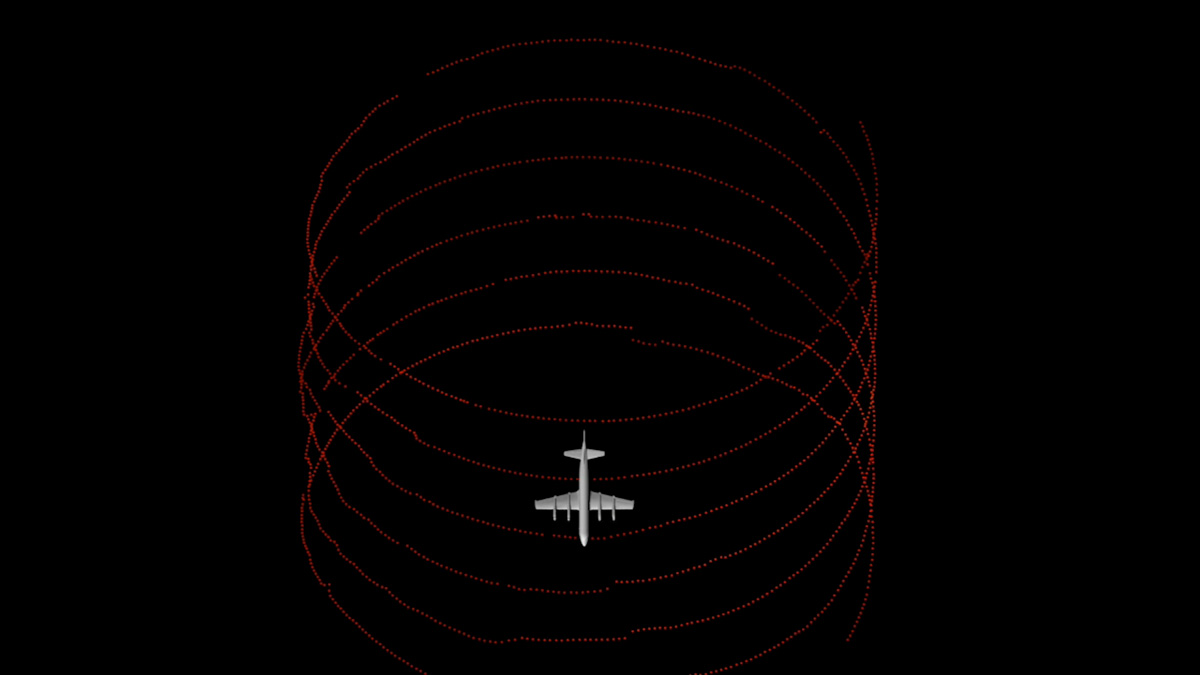

Firing laser pulses

With laser altimetry, laser instruments on board the research aircraft fire several thousand pulses of light every second. The results reveal the height of the surface below.

Spinning swath

The lasers spin in a circle that's 820 feet (250 meters) across, which provides a swath of data that an be transformed into a topographic map of the ice, NASA said.

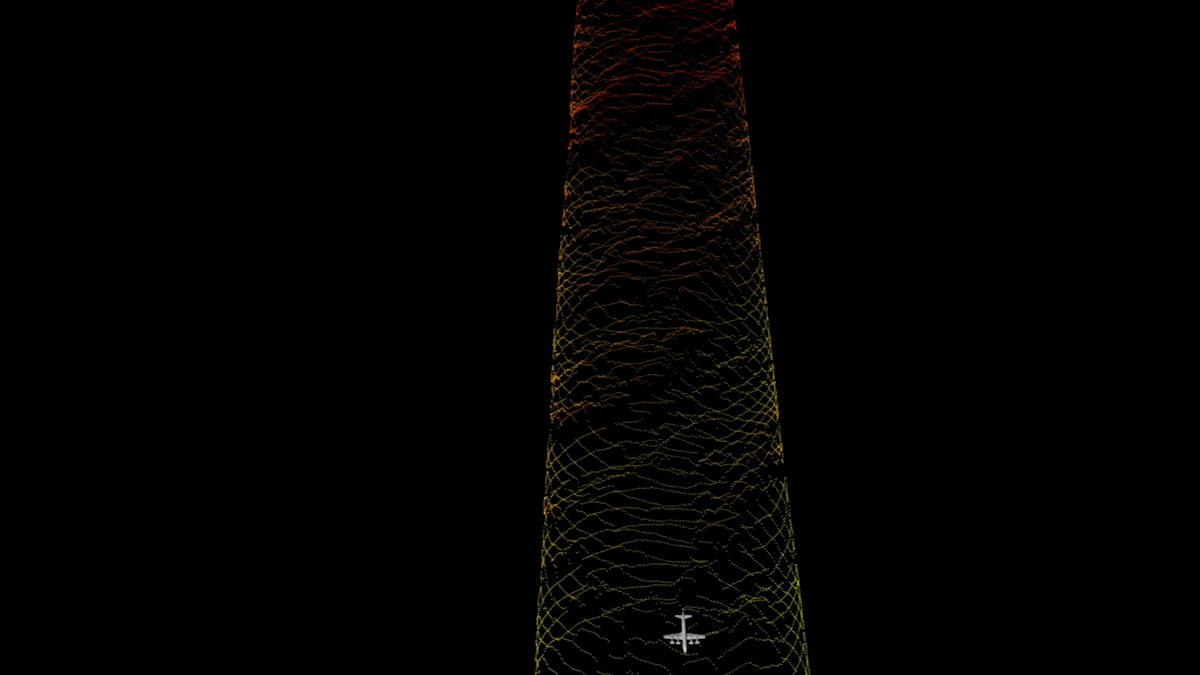

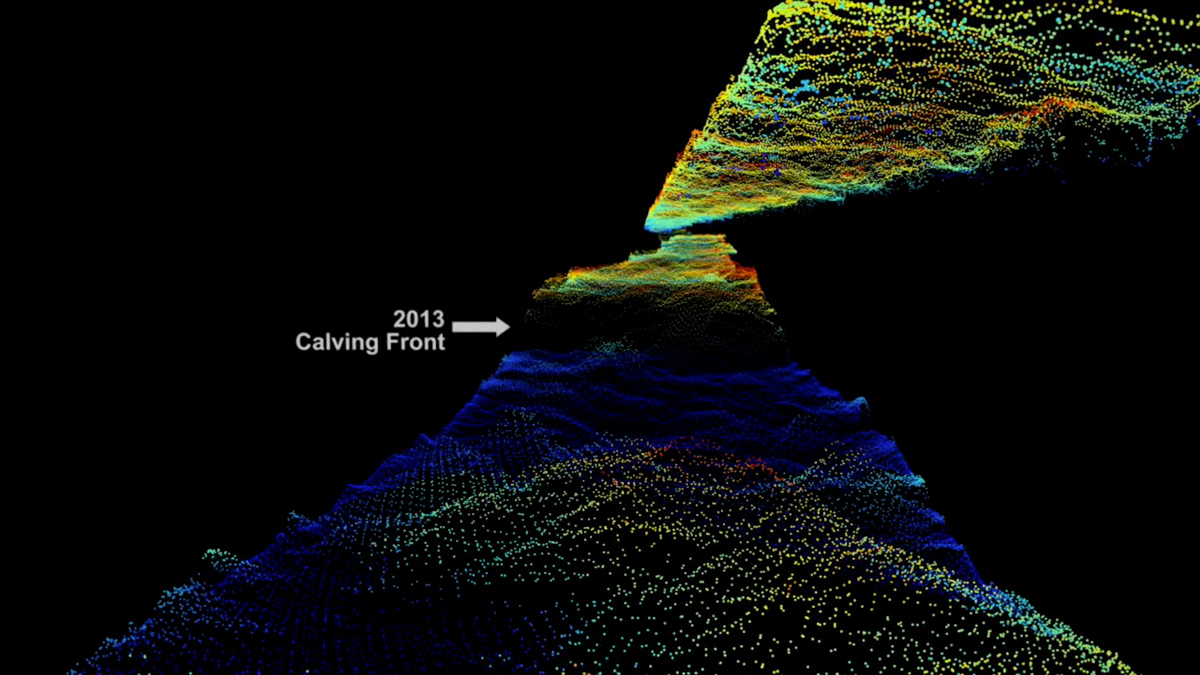

Elevation changes

Here, higher elevations on the glacier are shown in red and orange, while lower elevations are in green and blue.

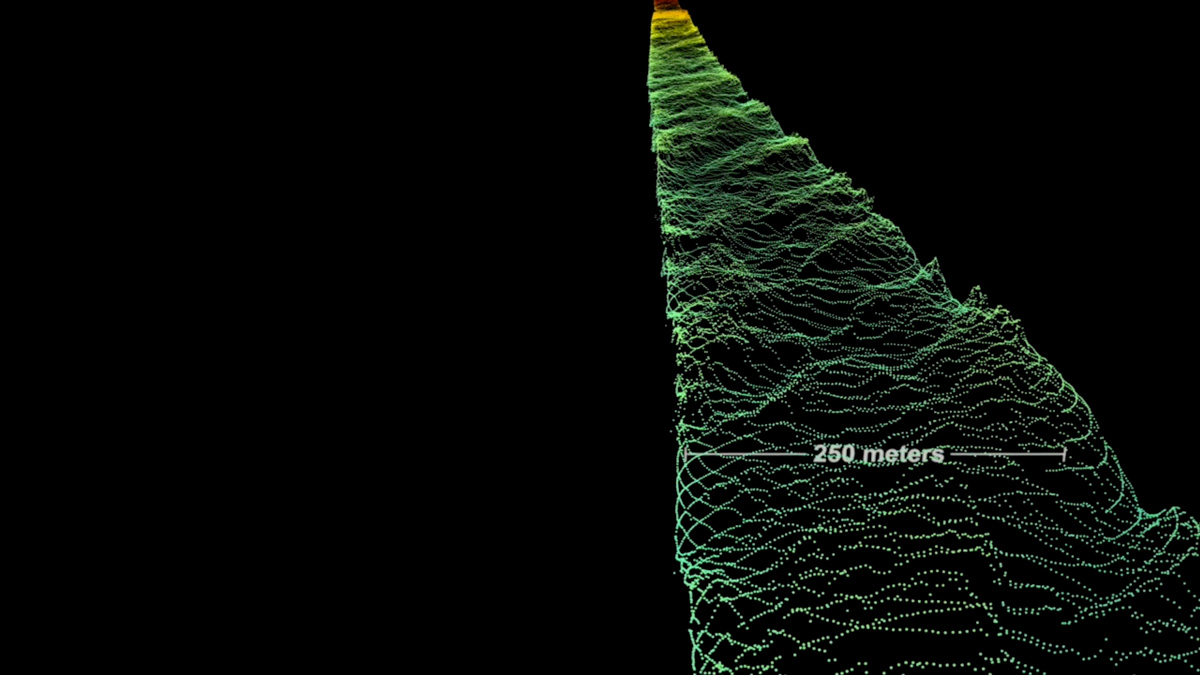

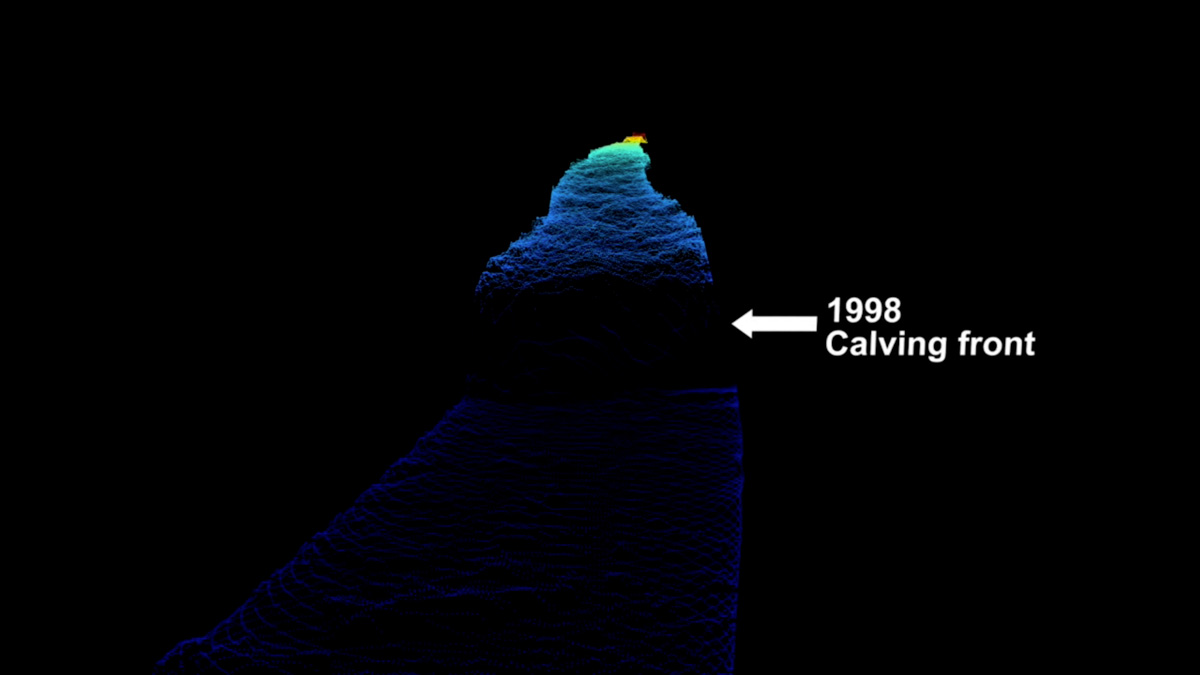

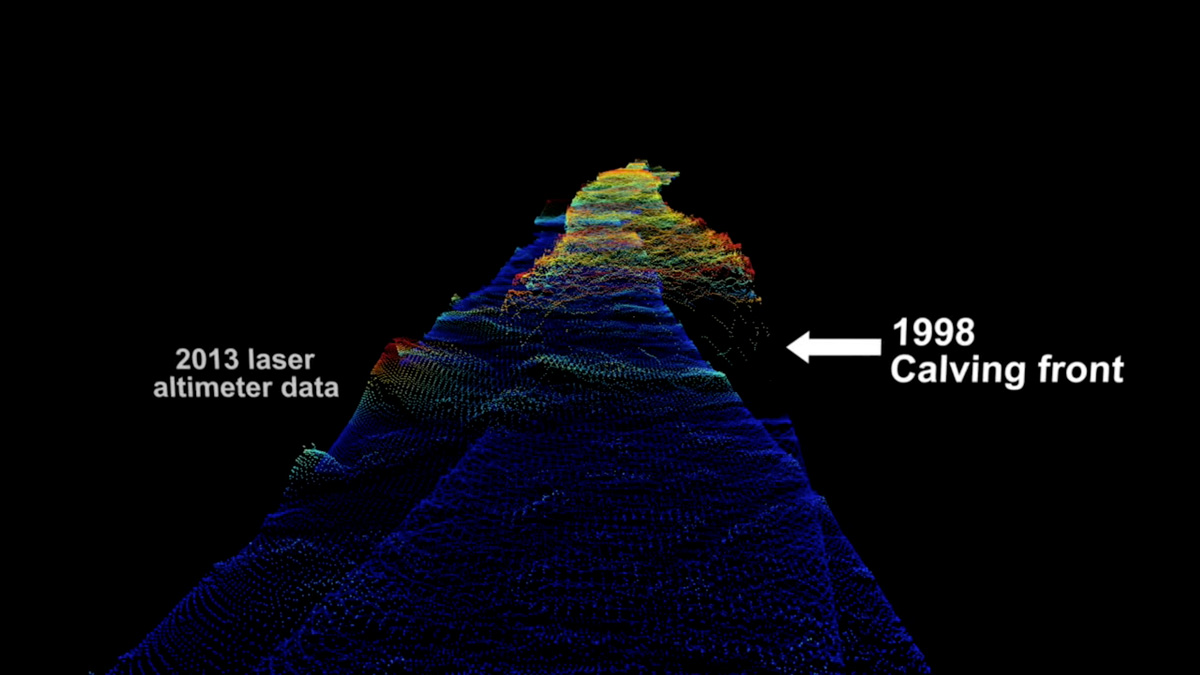

1998 calving event

The laser altimeters showed height measurements all the way down to the Helheim Glacier's calving front, where icebergs break off into the sea.

Icebergs break off

Here's a 1998 swath compared with one from 2013. In this image, the color scale is changed to show the local differences in elevation, according to NASA.

Retreat

The 2013 swath from the laser altimeters reveals that the calving front retreated significantly since 1998, by 2.5 miles (4 kilometers), according to the NASA video.

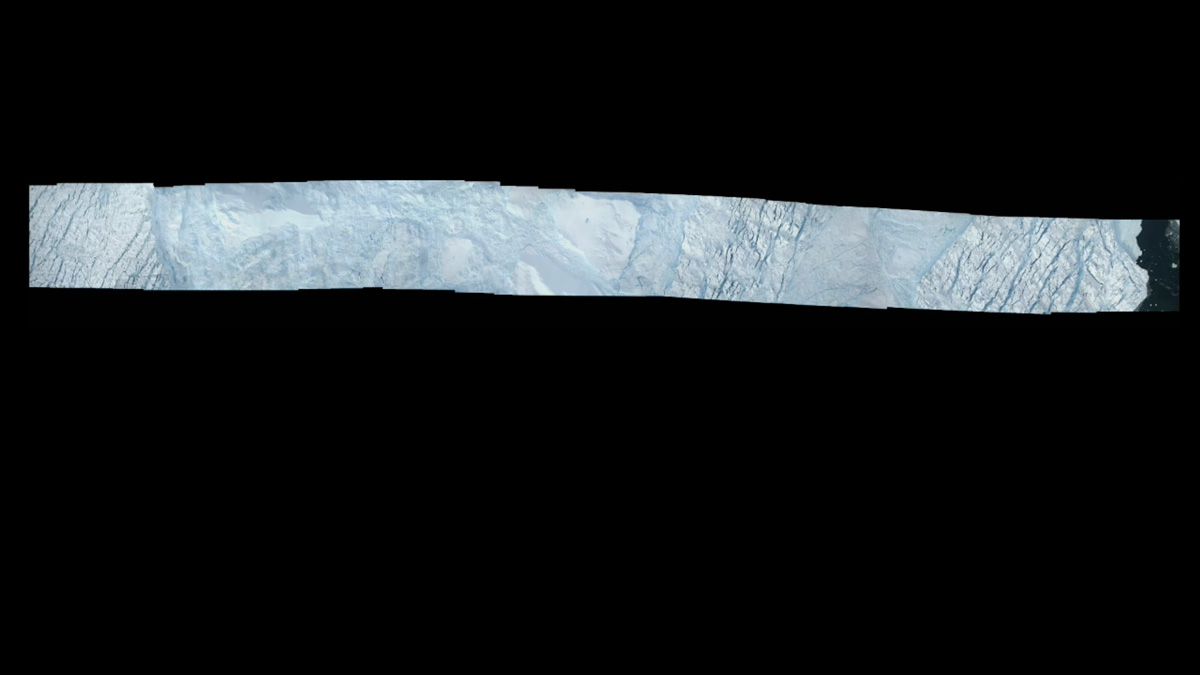

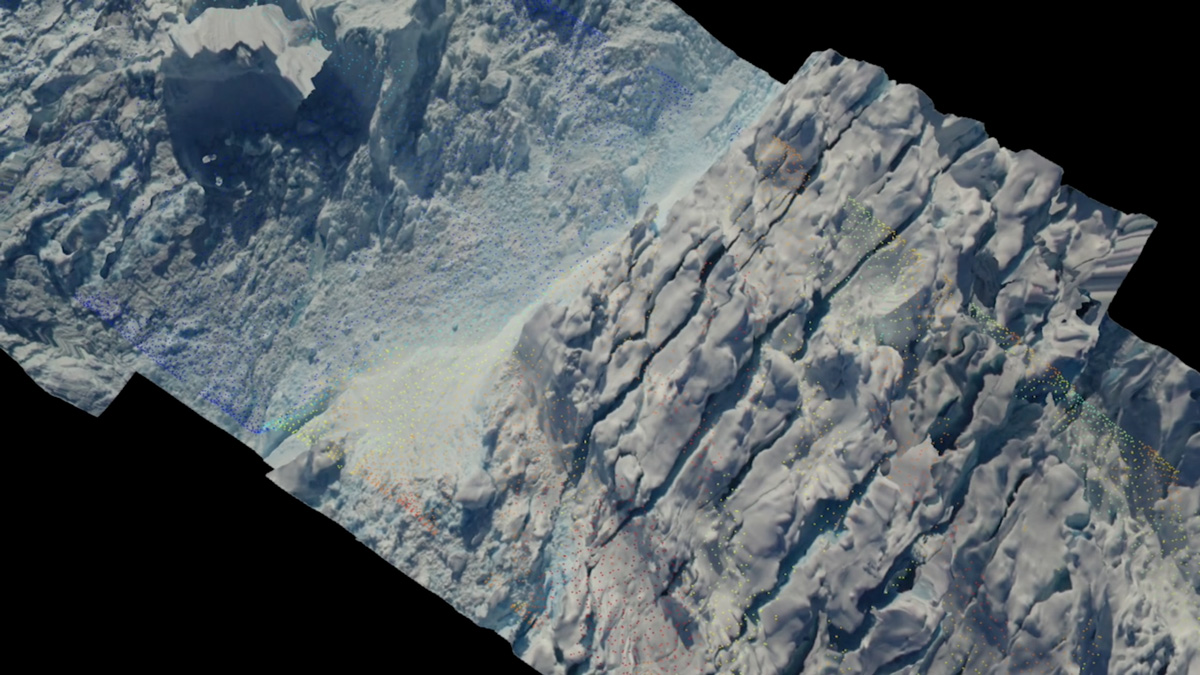

Gorgeous mosaic

NASA's Operation IceBridge mission has also used a high-resolution camera system to take overlapping images of the ice of Helheim Glacier throughout its 8-hour flights. These images can then be pieced together into a mosaic.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

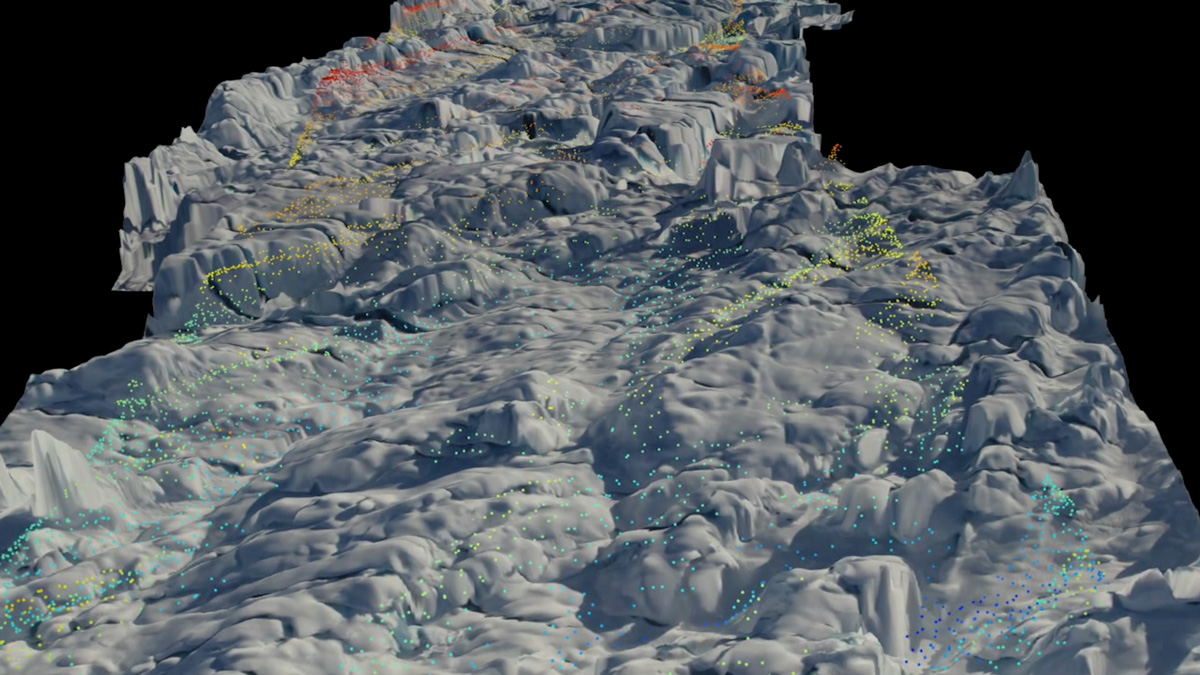

Stereoscopic view

Because the images overlap, they can provide scientists with a stereoscopic view of the ice and even elevation measurements. The NASA scientists overlaid the elevation information from the images on top of the measurements from the laser altimetry.

Steep calving front

Helheim's calving front, which is 70 feet (21 meters) high, can be seen here.

Springtime flights

Until the launch of a new NASA satellite called ICESat-2, the Operation IceBridge mission will return to Greenland every spring to continue monitoring the glacier, NASA said.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.