Photos: Primordial Worm Snatched Prey with Spines on Its Head

Spiny worm

More than 500 million years ago, a worm swam in the ocean's deep waters, hunting for tiny prey that it could capture with its 50 pointy spines. The worm was small, just 4 inches long (10 centimeters), but it would have been a formidable predator for small marine creatures that lived along the bottom of the ocean, such as larvae and small crustaceans that looked like shrimp.

The spiny worm, dubbed Capinatator praetermissus, was likely a forerunner of modern arrowworms, tiny marine worms that live and hunt in the above water column with other free-floating creatures. [Read the Full Story on the Spiny Worm]

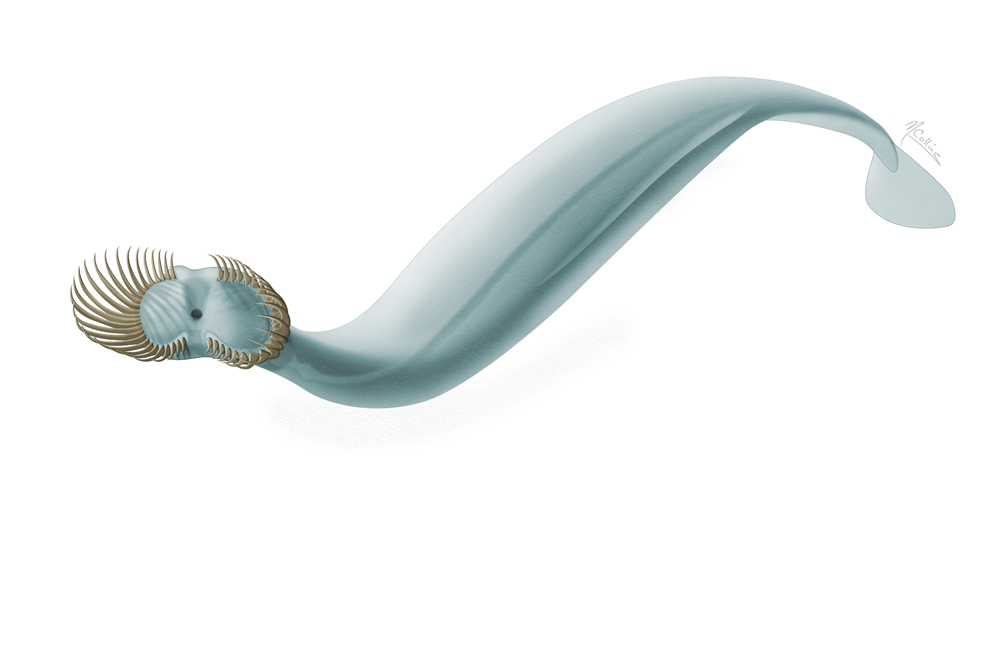

Ancient worm

This illustration depicts a large, primitive chaetognath, a well-preserved specimen of a newly identified species called Capinatator praetermissus. The species — which has smaller, modern relatives that chow on plankton — was identified from 508-million-year-old Burgess Shale fossils.

Multiple spines

This marine worm had almost twice as many pairs of spines that it used to capture prey — up to 25 pairs — as its modern-day counterparts. The pictured specimen was uncovered in Burgess Shale at Walcott Quarry in British Columbia's Yoho National Park.

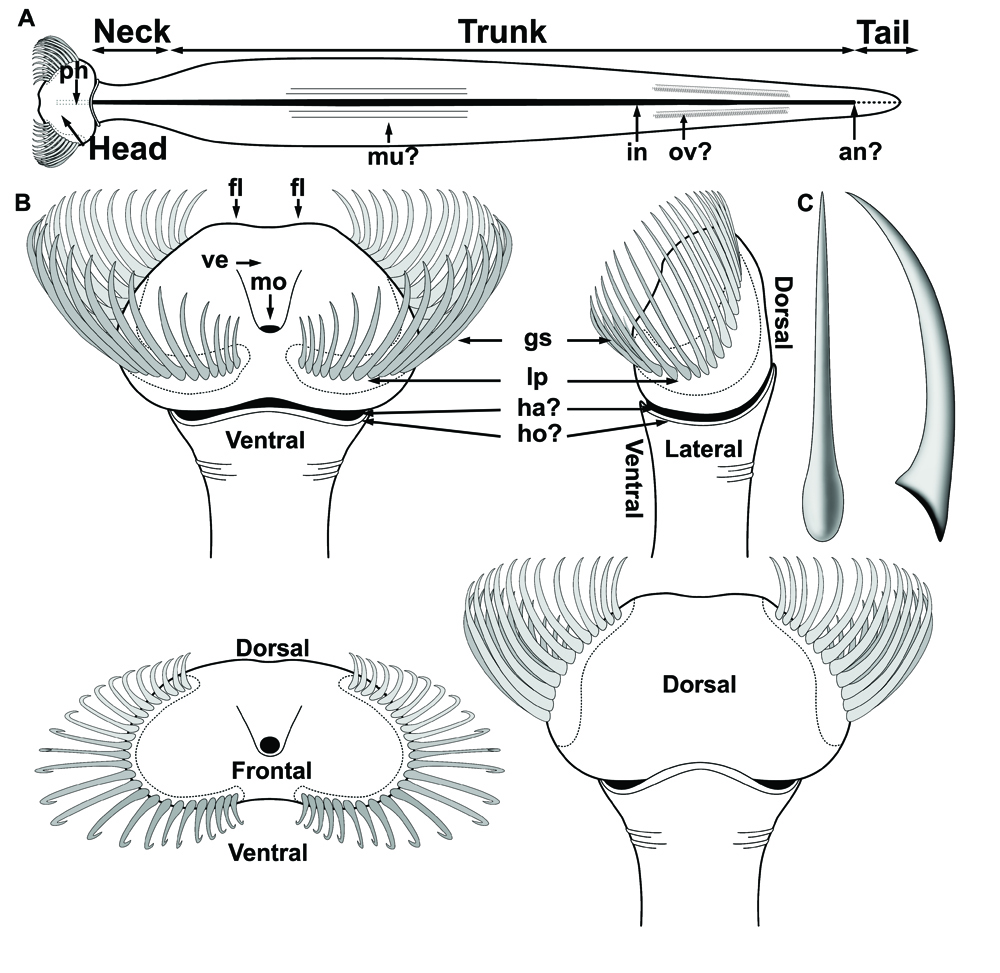

Wormy details

A diagram of the C. praetermissus shows the sections of the marine worm from multiple angles.

Best look

This specimen, from the Collins Quarry at Mount Stephen in British Columbia, displays the most complete C. praetermissus on record. The fossil is 3 inches (7.5 cm) long and has spines on the left and the posterior to the right.

In addition, part of its gut is clearly visible in the middle of the specimen. The marine worm is believed to be a bottom-feeder, whereas its modern cousins live in the water column with other free-floating creatures.

Eating appendages

The Royal Ontario Museum houses 48 of the 49 worm specimens, many of which still have their feeding apparatuses attached to their heads. Others have fossilized evidence of the rest of their bodies.

The other specimen, at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., has a single set of grasping appendages.

Teamwork

At a 1983 fieldwork expedition on Mount Stephen in the Canadian Rockies, a Royal Ontario Museum team, led by Desmond Collins, uncovered several Burgess Shale-type fossils that were identified later as C. praetermissus.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rocky history

During the 1983 dig, members of the Royal Ontario Museum team collected fossils of C. praetermissus , which is now identified not only as a new species but also a new genus (Capinatator) of ancient marine creature.

Famous location

The Burgess Shale fossil sites on Mount Stephen and in the nearby Walcott Quarry in Canada's Yoho National Park are acclaimed for the well-preserved marine fossils from the so-called explosion of life that prospered during the Cambrian period.

[Read the full story on the spiny worm]