Four-legged Creature's Footprints Force Evolution Rethink

Four-legged creatures were mucking around a muddy basin in what is now Poland about 397 million years ago. And they left behind distinctive footprints, which have turned back the clock on the evolution of these landlubbers.

Scientists discovered the fossilized prints, which included various trackways and isolated prints, in the Holy Cross Mountains in southeastern Poland. Analyses suggest most if not all of them came from different tetrapod species — which are four-legged animals that had backbones, such as amphibians — with some possibly belonging to juveniles and adults of the same species.

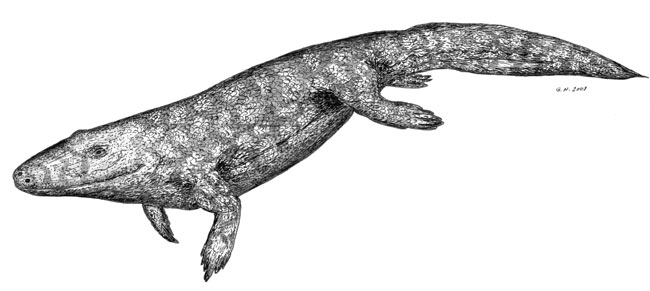

The land creatures likely had bodies shaped somewhat like crocodiles, with fin-like tails and stumpy legs. And some of them were pretty big, reaching up to about 10 feet (3 meters) in length, the researchers said.

The discovery helps to refine the timing of the transition from our fishy ancestors to land creatures, which until now was thought to have occurred about 380 million years ago or so. The new discoveries show the four-leggers were stomping around millions of years earlier than had been estimated based on fossils. Until now, the earliest complete evidence for a four-limbed animal with digits came from Ichthyostega and Acanthostega, which date back to between 374 million and 359 million years ago.

"We didn't know they existed at this point, and we would not have expected to have found them in this environment," study researcher Per Ahlberg of Uppsala University in Sweden said in a telephone interview.

Since scientists have used modern amphibians and such as models for the earliest tetrapods, some have assumed the earliest four-limbed creatures emerged from a freshwater environment, Ahlberg said.

Not so, according to the new prints.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It seems like it was a very extensive muddy basin, marine basin, that was very shallow and very wide, hundreds of kilometers wide," said study scientist Marek Narkiewicz of the Polish Geological Institute, adding that the basin likely dried out every few years or so.

That drying out may have been an evolutionary boost needed to get fishy animals up onto the land, he speculated. "When we have an animal that's adjusted to swim and then it's left stranded during desiccation, during drying out, and if it doesn't have the ability to walk then of course it's death," Narkiewicz told LiveScience.

The animals were likely adept swimmers and walkers, Ahlberg said. "They're trying their terrestrial skills out in the intertidal zone, and it's only later that we find they are moving onto the land proper," Ahlberg said.

The testing ground was likely intertidal, with ebbs and flows on a daily basis. So when the tide came in, the animals would have swam around and when the water receded to expose mud banks, like the one where the prints were found, the animals would have easily snagged any food that washed up, Ahlberg said.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.