First 'Winged' Mammals Lived Alongside Dinosaurs 160 Million Years Ago

Both newly identified species lived about 160 million years ago, making them the oldest-known mammal-like gliders on record, the researchers said.

"I was stunned when first seeing these specimens — they looked as if they just fell flat into a shallow lake, with limbs and their gliding membranes spread perfectly out, fossilized for eternity," the studies' lead researcher, Zhe-Xi Luo, a paleontologist and professor of evolutionary biology at the University of Chicago, told Live Science in an email. "They are almost like modern mammal gliders!" [See Images of the Jurassic-Age Gliders]

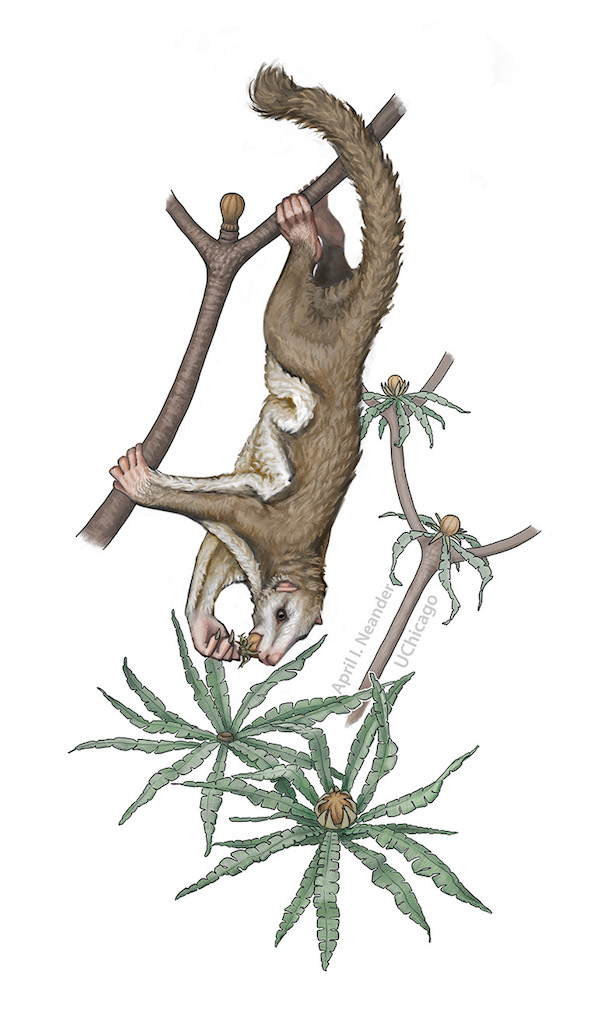

Both fossilized mammaliaforms (precursors of mammals) were discovered in northeast China. Researchers named the larger one Maiopatagium furculiferum, with the genus name translating to "mother of animals with patagia," the Latin word for gliding membrane. Maiopatagium is similar to a North American gliding squirrel, measuring almost 10 inches (23 centimeters) long and weighing about 5 ounces (170 grams), Luo said.

The genus name of the slightly smaller creature, Vilevolodon diplomylos, means "glider tooth" in Latin and Greek. Both animals had agile limbs and patagia, allowing them to climb trees and glide from high places.

Ancient gliders

Given that both gliders "are quite primitive," it's a refreshing surprise to learn that these animals developed the adaptation of flying among the Jurassic trees, Luo said.

"Who would have thought even the mammaliaform forerunners had developed modern mammal-like gliding and took to [the] air?" he said.

Vilevolodonis about half as long and has one-third the body mass of Maiopatagium, which suggests that this animal couldn't fly as far. "But among [living] rodent and marsupial gliders, the small gliders are more maneuverable and flexible than closely related, larger gliders," Luo said. "So, to be smaller, like Vilevolodon, has its own advantage as well."Luo and his colleagues spent three years analyzing both specimens, gathering clues about how the gliders lived during the dinosaur age. For instance, the researchers suspect that because Maiopatagiumwas about the same size as a modern sugar glider (Petaurus breviceps), the ancient animal could probably glide a similar distance: almost 100 feet (30 meters), Luo said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Toothy discoveries

Luo and his team also examined the gliders' teeth and found that the creatures likely ate seeds or the soft parts of plants, much like modern gliders do. [Image Gallery: Evolution's Most Extreme Mammals]

The teeth of Maiopatagium are just like the teeth of a modern fruit-eating bat, although the ancient and modern animals are unrelated, Luo said. In comparison, Vilevolodon's teeth look like those of a modern seed-eating squirrel, even though the two creatures aren't relatives.

However, while these ancient animals likely munched on ferns, cycads (seed-bearing plants with woody trunks), ginkgoes and conifers, modern-day gliders mostly dine on flowering plants (angiosperms), which didn't develop until about 140 million years ago, Live Science previously reported.

Despite these culinary differences, it's likely that flying mammals developed similar diets through convergent evolution, a process in which unrelated animals develop similar characteristics, the researchers said.

In all, these newfound species show that reptiles weren't the only type of animal diversifying during the Mesozoic, or dinosaur age.

"These new discoveries simply suggest that mammals are more diverse … than previously thought," Luo said.

The two studies were published online today (Aug. 9) in the journal Nature.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.