Medieval Gospel Made of Sheep, Calves, Deer ... and Goat?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

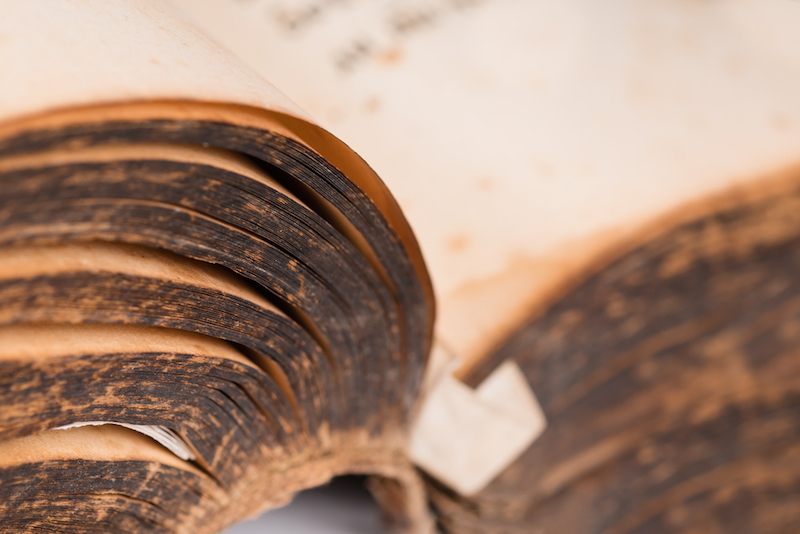

During medieval times, bookmakers fashioned the pages and cover of a rare copy of the Gospel of Luke out of five different types of animals: calves, two species of deer, sheep and goat, according to new research.

In addition, one more type of animal left its mark on the cover of this 12th-century book: Beetle larvae likely chewed holes into the leather binding, the researchers said.

Now, researchers are learning unexpected secrets about the manuscript by noninvasively testing the proteins and DNA on the book's pages, the researchers told Live Science. [Cracking Codices: 10 of the Most Mysterious Ancient Manuscripts]

Research roadblocks

Rare books — such as this copy of the Gospel of Luke — are difficult to study because they're fragile, prompting many librarians to bar any research that would harm such manuscripts or their pages.

This rule is all too familiar to Matthew Collins, a biochemist at both the University of York in the United Kingdom and the University of Copenhagen. He wanted to sample parchments — documents made from animal skins — as a way to determine how people have managed livestock throughout history.

When Collins and Sarah Fiddyment, a postdoctoral fellow of archaeology at the University of York, approached librarians at the University of York's Borthwick Institute for Archives, "we were told that we would not be allowed to physically sample any of the parchment documents, as they are too valuable as cultural-heritage objects," Fiddyment told Live Science.

But Fiddyment didn't give up. She spent several months learning how librarians conserve rare parchments, and, surprisingly, found a new method that allows scientists to study these specimens without disturbing them — one that involves an eraser.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Typically, librarians "dry clean" parchments by gently rubbing a polyvinyl chloride eraser against them. This technique pulls fibers off the page, and the resulting debris is usually thrown away.

But Fiddyment realized this debris held valuable clues about the book. By isolating proteins and other biological fragments within the debris, and examining them with a mass spectrometer — an instrument that identifies different compounds by their masses — researchers could learn all kinds of information about the manuscripts, she found.

"This was Sarah's brilliant idea," Collins told Live Science in an email. "Oddly enough, I think we relished the challenge."

Rare analysis

It wasn't long before Fiddyment put this technique into action. A historian bought the aforementioned Gospel of Luke at a 2009 Southeby's auction. An analysis of its "prickly" style of script indicated that scribes at St. Augustine's Abbey in Canterbury, in the United Kingdom, created it around A.D. 1120, Bruce Barker-Benfield, the curator of manuscripts at the Bodleian Libraries at the University of Oxford, told the journal Science.

To learn more about the gospel, the historian contacted Collins. Using Fiddyment's method, Collins and his colleagues learned that the book's white leather cover came from the skin of a roe deer— a common species in the United Kingdom. The book's strap came from a larger deer species — either a native red deer or a fallow deer, an invasive species likely brought from continental Europe after the Normans invaded in 1066.

Perhaps the book's materials exemplify the period when roe deer numbers were falling, prompting monasteries to turn to larger deer to make books, Fiddyment told Science. Many monasteries began scriptoriums at the request of the Normans, and the rising demand for animal skins likely had a "huge impact" on the animals the monasteries raised, Naomi Sykes, a zooarchaeologist at the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom, told Science.

An analysis of each page revealed that the manuscript's darker-colored sheets were made of goat skin — an unusual choice, because goat parchment was typically used by less affluent bookmakers. Perhaps the medieval monks had exhausted their supplies of calves of lambs, and had turned to goats to make ends meet, the researchers said. [Image Gallery: Ancient Texts Go Online]

Alternatively, the monks may have had sheep, but decided to let them live to adulthood so they would have more wool to harvest, Collins told Science.

In all, the researchers found that the 156-page manuscript was made from the skin of 8.5 calves, 10.5 sheep and half a goat.

"We did not expect to find such a varied range of animals used in one document," Fiddyment told Live Science. "[It] brings up many questions about manuscript production and availability of livestock."

The researchers also noticed a strange detail about the handwriting. "[It] had been staring us in the face all along, the fact that there were two major scribes and the real change in order of the skins happened when the second scribe takes over the text," Collins told Live Science. "We don't know how long the transfer took, but not only did Bruce [Barker-Benfield] identify the fact that [the scribe] was less skilled, it seems that he had access only to (lower value) sheep skin."

Going forward, the new method may help researchers uncover a vast trove of biomolecular data, including information about the breed diversity of animals whose skins were used in parchment through time, which could, in turn, help researchers learn about livestock economies, Fiddyment said. This technique can also reveal information about the microbiome of people who touched the parchments over the ages, Fiddyment noted.

Collins agreed, saying that archaeologists pay more attention to parchment than they have in the past. "It is much easier to study archives and curated parchment collections than fragments of animal bone, which were often poorly recorded in early excavations of sites, such as monasteries," he said. "Only one parchment production site has ever been recognized and properly excavated, and we remain remarkably ignorant of production processes."

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus