In Photos: Eclipse-Chasing Jets Aim to Get Best-Ever View of Sun's Corona

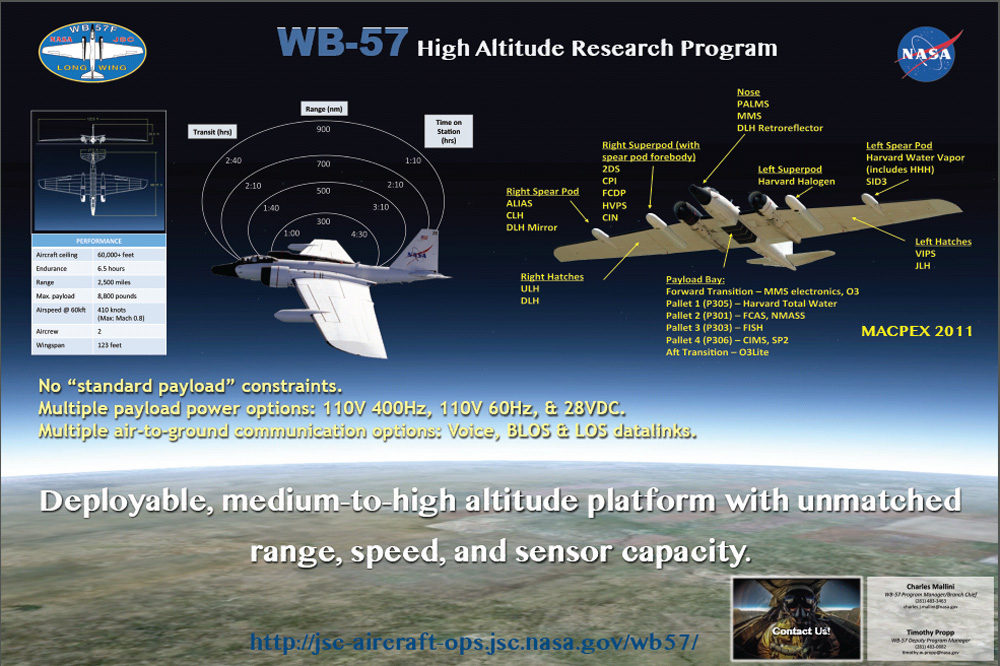

High-altitude research jets

The pilots of two of NASA's WB-57 high-altitude research jets will enjoy what may be the best view ever of a total solar eclipse on Aug. 21, when they chase the moon's shadow over Missouri, Illinois and Tennessee at an altitude to 50,000 feet (15,200 meters).

By carefully timing their flights, the two jets will combine to use their stabilized onboard camera equipment to observe the totality of the eclipse for 7 minutes, around three times longer than the two-and-a-half minutes experienced by eclipse observers on the ground. [Read more about the eclipse-chasing jets]

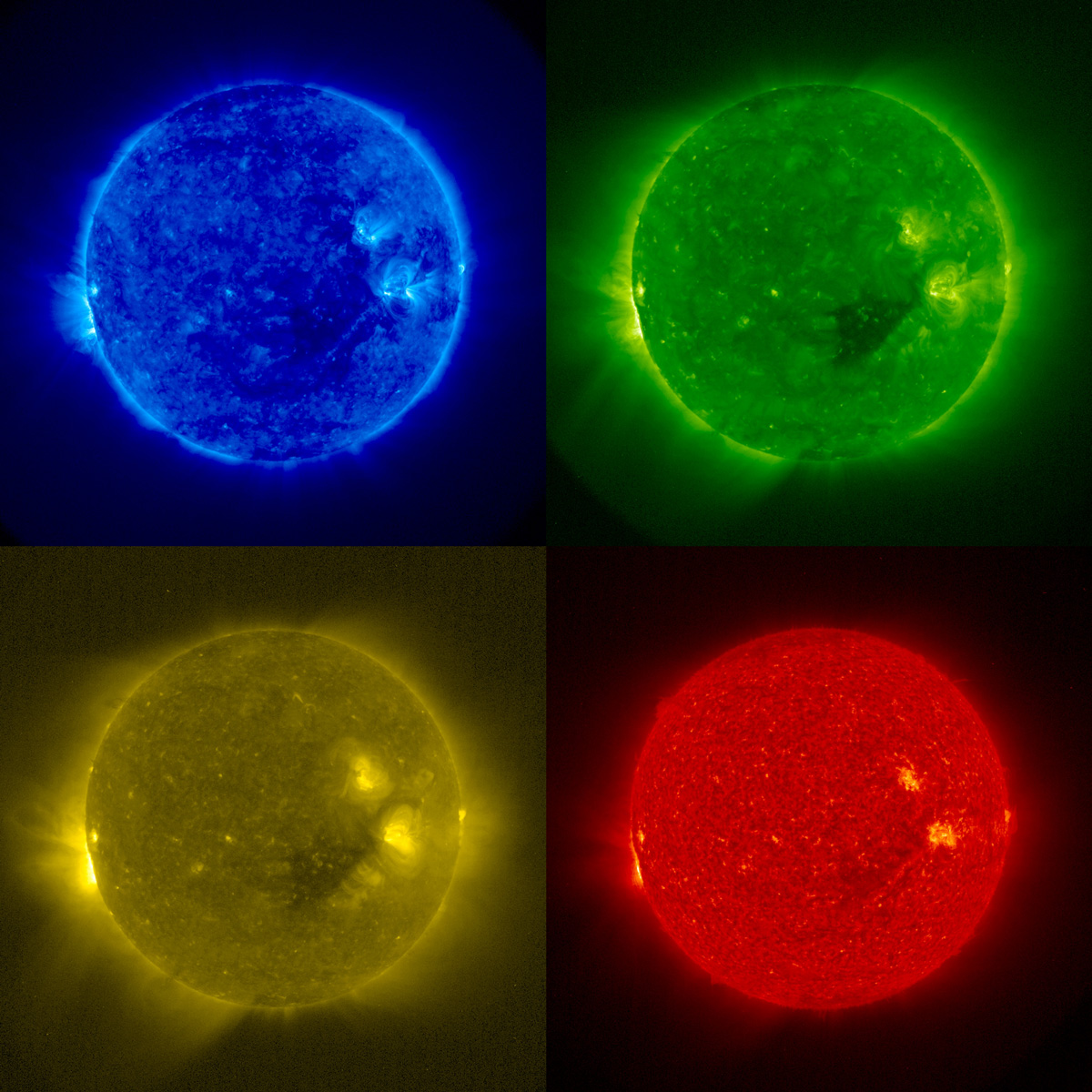

Solar corona

The NASA jets will use their cameras to make detailed moving images of the solar corona for a team of scientists led by Amir Caspi, an astrophysicist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

The corona is the hot outermost layer of the sun's atmosphere, which only becomes visible during a solar eclipse when the disk of the moon blocks out the disk of the sun.

How they work

NASA's WB-57 research jets are adapted from B-57 Canberra bombers that were used by the U.S. Air Force in the 1960s to detect traces of nuclear testing in the upper atmosphere.

The planes have been extensively retrofitted with atmospheric sensors and instruments to fly a variety of high-altitude research missions. The stabilized camera platform that will be used by the jets during the eclipse was developed to track NASA's space shuttles during re-entry to the atmosphere.

Teamwork at its best

The high-resolution cameras that will be used for the eclipse observations are housed in the noses of the jets.

The moon's shadow travels even faster than the jets can fly, so the pilots will need to fly in formation, about 62 miles (100 km) apart, so that the second aircraft can start its observations of the totality a few seconds before the totality ends for the first aircraft.

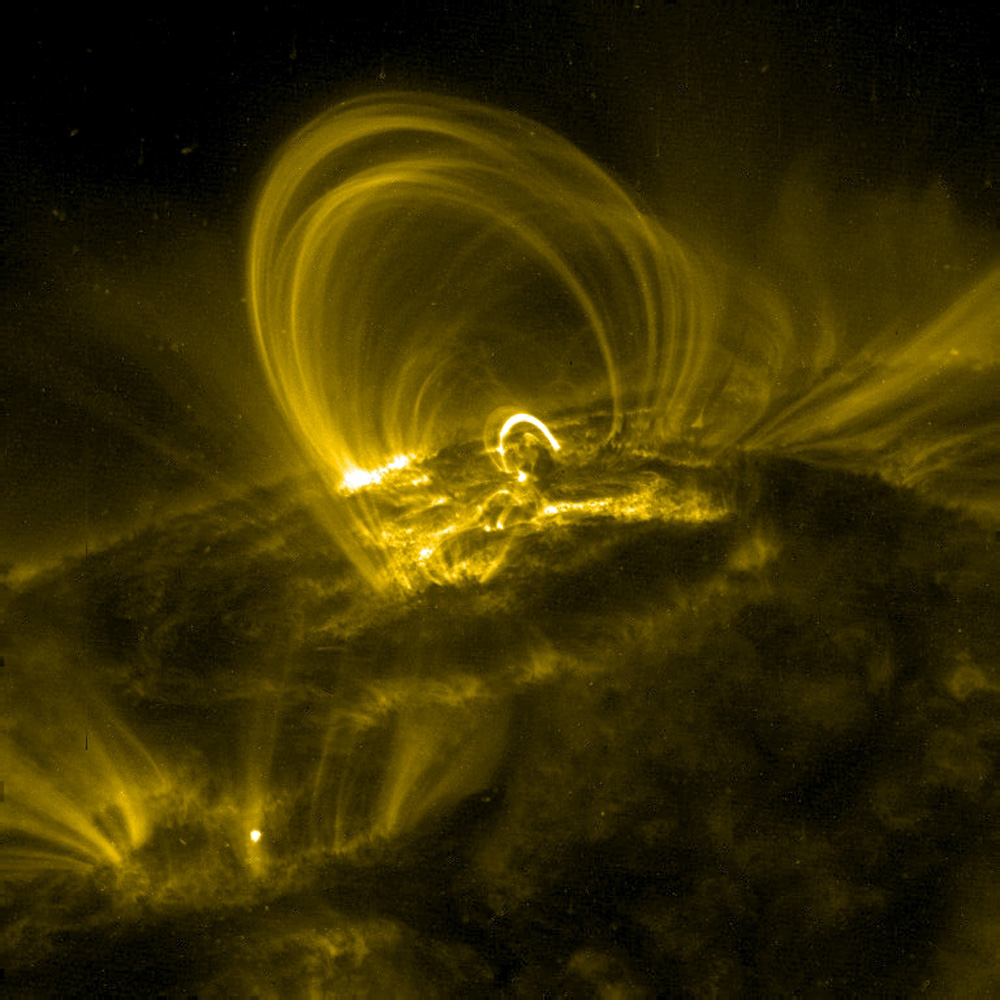

Dynamic structure

The jet cameras will be able to make unprecedented moving images of the eclipse totality for more than 7 minutes, giving the astrophysics team a detailed look at dynamic structures within the sun's corona. The researchers hope to be able to identify processes in the sun's magnetic field that make the corona much hotter than the surface of the sun itself.

Understanding our star

The researchers also hope to learn more about how the sun's magnetic field creates smooth visible structures in the corona, such as loops and streamers.

The magnetic field lines are rooted in the chaotic surface of the sun itself, and computer models suggest they should become a "tangled mat" of magnetic field lines, instead of the smooth structures that are seen, Caspi said.

A clear view

By using cameras at an altitude of 50,000 feet (15,200 m) to observe the eclipse, the researchers can be certain of perfect weather for the duration of the celestial event, Caspi said.

The high-altitude cameras will also be above around 90 percent of the Earth's atmosphere and 99 percent of its water vapor, which will reduce distortion to a minimum and allow the cameras to detect very fine dynamic changes in the corona.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

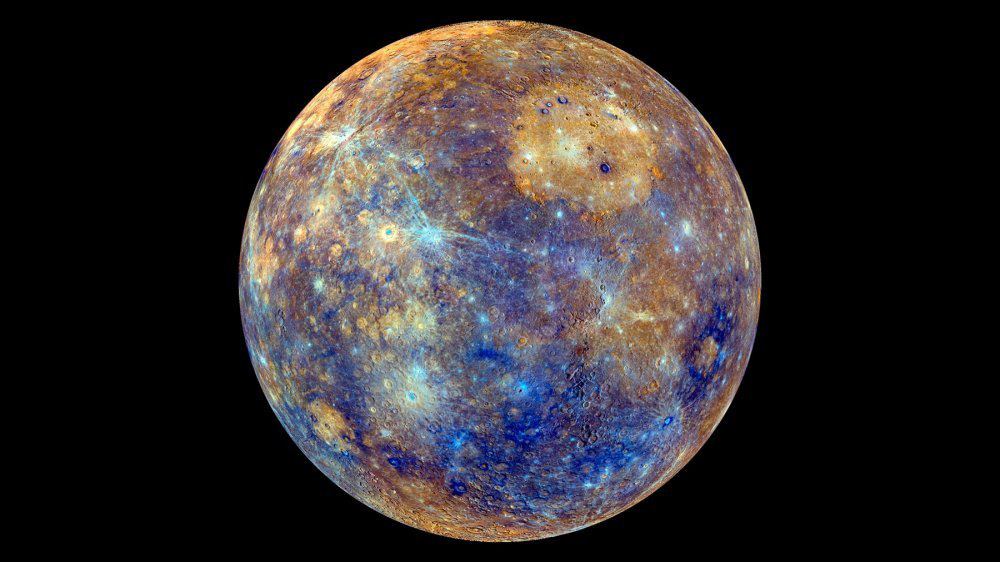

Seeing the unseen

The jet cameras will also be used to observe the planet Mercury for half an hour before and half an hour after the eclipse totality. Mercury is often difficult to observe because it is so close to the sun, but it will become visible in the darkened sky during the partial and total phases of the Aug. 21 eclipse.

First-time look

Although NASA's Messenger probe, shown here, has mapped the surface of Mercury with X-rays, the researchers will use the camera's data from the eclipse-chasing jets to make observations of the surface with infrared light for the first time.

They hope the infrared images will reveal the temperatures of Mercury's surface near the planet's dawn terminator, where it moves from freezing night to scorching-hot day.

Searching for theories

The researchers will also search their images for Vulcanoids, a type of asteroid theorized to exist between the orbit of Mercury and the sun, but which have never been seen to date.

Data from the observations gathered by the researchers will be shared with teams of scientists around the world, and a live video feed from the jets' cameras, transmitted by a Viacom satellite, will be available to the public during the eclipse itself.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.