Icy Planets' Diamond Rain Created in Laser Laboratory

For the first time, the kind of diamond rain that scientists think falls within the icy giant planets of the solar system has been generated in the lab, a new study finds.

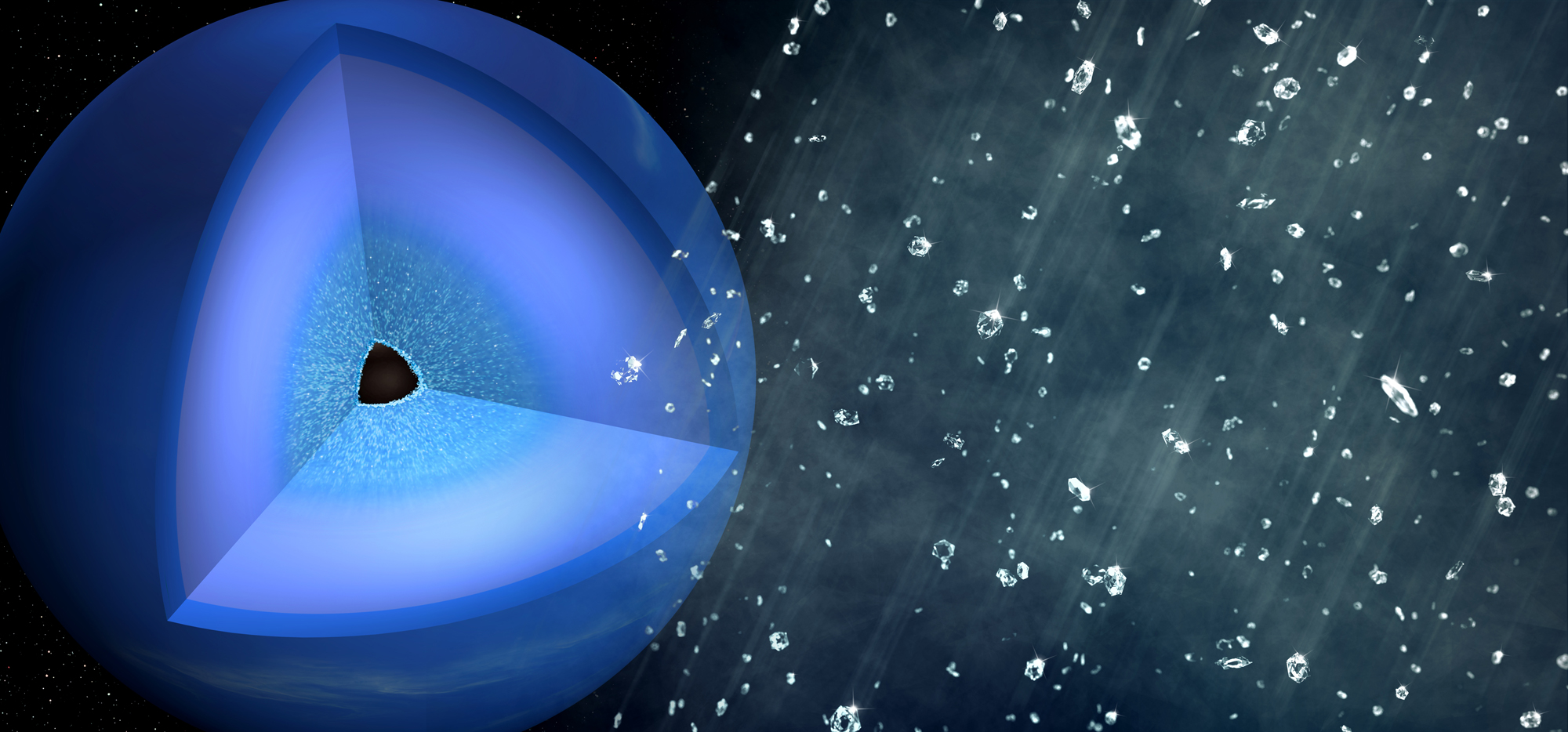

Thousands of miles below the surfaces of icy giant planets such as Neptune and Uranus, carbon and hydrogen are thought to compress under extreme heat and pressure to form diamonds, according to previous research going back 30 years. These diamonds are then thought to sink through the layers of the gas giant planets, creating a "diamond rain" that eventually settles around the planetary cores.

However, until now, scientists could not confirm whether, when and how such diamond rain could actually form in the chemistry, temperatures and pressures found deep within ice giants. [Our Solar System: A Photo Tour of the Planets]

Researchers simulated the interior of ice giants by creating shock waves in polystyrene (a kind of plastic) with an intense laser at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in Menlo Park, California. The polystyrene simulated molecules known as hydrocarbons that are derived from methane, the compound that gives Neptune its blue tint. These hydrocarbons are what diamonds are thought to form from in the high pressures and temperatures in the intermediate layers of ice giants.

The scientists used the laser to generate pairs of shock waves, with the first member of each pair overtaken by its stronger partner. When the shock waves overlapped, diamonds formed at temperatures of about 8,540 degrees Fahrenheit (4,725 degrees Celsius) and pressures about 1.48 million times greater than Earth's atmospheric pressure at sea level. Such conditions resemble the environments about 6,200 miles (10,000 kilometers) below the surfaces of Neptune and Uranus, the researchers said.

"It was very surprising that we got such a clear diamond signature and that the diamonds formed so quickly," said study lead author Dominik Kraus, an experimental laser-plasma physicist at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf research laboratory in Germany, told Space.com. "I was expecting to look for very tiny hints in the data, and our theorist co-workers actually predicted that it might be impossible to observe diamond formation in our experiment. I already prepared my team for a very difficult experiment and data analysis. But then, the data was just incredibly clear from the first moments in the experiment."

As the diamonds were born, the scientists analyzed them using intense, fast pulses of X-rays only 50 femtoseconds long — essentially, the "shutter speed" of this laser camera is 50 millionths of a billionth of a second, and can thus capture very-fast-moving chemical reactions. These X-ray snapshots helped capture the exact chemical composition and molecular structures of the diamonds as they formed.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the experiments, the researchers saw that nearly every carbon atom of the plastic targets got incorporated into diamonds up to a few nanometers (billionths of a meter) wide. They predicted that if similar reactions happened within Neptune and Uranus, diamonds could become much larger, perhaps millions of carats large. (One carat is 200 milligrams, or 0.007 ounces.)

But don't expect these findings to generate a rush of diamond miners to Neptune or Uranus.

"The diamonds created in ice giants and our experiment are certainly not gem-quality cut and polished brilliants," Kraus told Space.com. Instead, they are probably spherical diamonds loaded with impurities, he said.

The researchers suggested that over thousands of years, these diamonds would slowly sink through the icy layers within ice giants, assembling into a thick layer around the cores of these planets.

"Some models predict that the temperature around the core may be high enough that diamond would melt, forming underground seas of liquid metallic carbon, maybe with some diamond 'icebergs' swimming on top," Kraus said. "This could help to explain the unusual magnetic fields of Uranus and Neptune. However, most models suggest that diamond would remain solid around the cores of Neptune and Uranus."

As these diamonds rain downward, they are expected to generate heat, much as meteors burn as they plummet through Earth's atmosphere. This heat could help explain why Neptune is hotter than expected, Kraus said.

Moreover, these new findings could help shed light on the inner workings of distant planets outside the solar system and, in turn, help researchers better model and classify such exoplanets, Kraus said.

The researchers added that one day, the microscopic "nanodiamonds" they created could be harvested for commercial purposes, such as medicine and electronics. Currently, nanodiamonds are commercially produced using explosives, and "high-energy lasers may be able to provide a more elegant and controllable method," Kraus said. However, the lasers they use currently accelerate the diamonds they create to very high speeds of about 11,185 mph (18,000 km/h), "and we need to gently stop them," he said.

Furthermore, these findings could help researchers understand and improve experiments that seek to generate energy from nuclear fusion. In some of these experiments, hydrogen fuel is surrounded by a layer of plastic and is then blasted with lasers, and these new findings suggest "that considering chemical processes may be important for modeling some types of fusion implosions," Kraus said.

Future research can investigate the roles that other elements — such as oxygen, nitrogen and helium — might play in ice giants, Kraus said. He and his colleagues detailed their findings online Aug. 21 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.