Mammoth Tooth Reveals Beast Once Tramped Around Austin, Texas

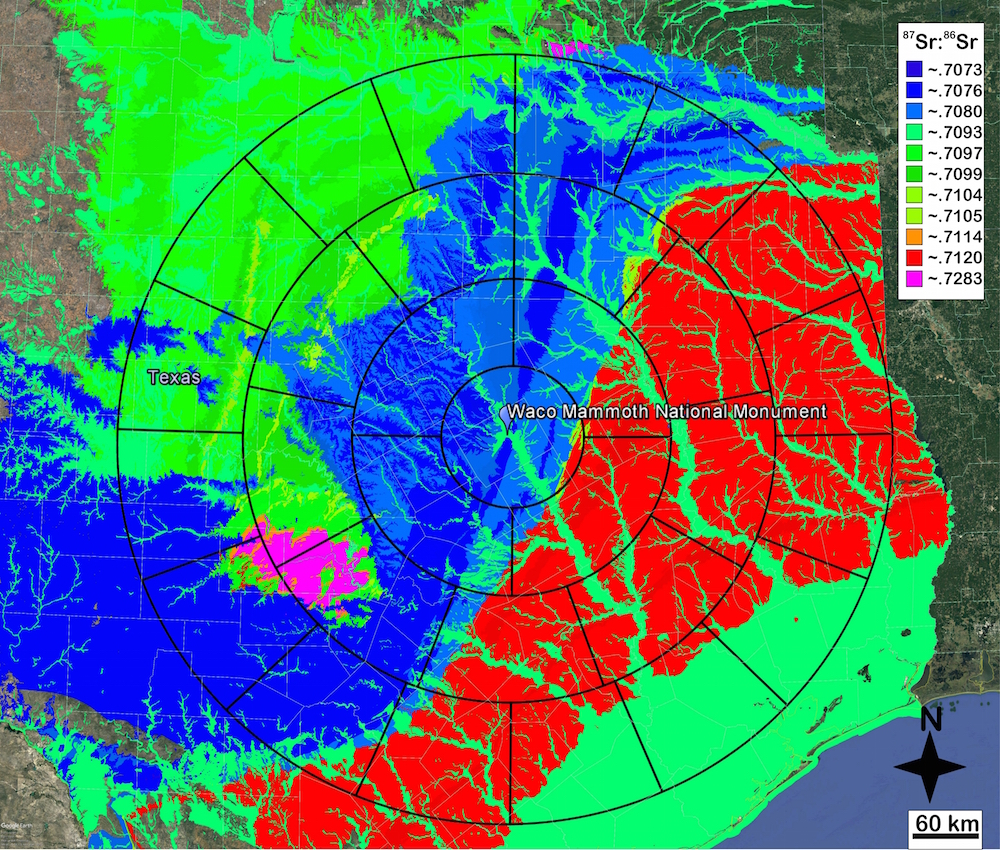

CALGARY, Alberta — About 67,000 years ago, a gigantic mammoth chowed down on enormous mouthfuls of grass in Texas, just west of where modern-day Austin is located, according to new research.

The finding is surprising, given that the beast's remains were discovered in Waco, Texas, more than 120 miles (200 kilometers) away from the Columbian mammoth's (Mammuthus columbi) ancient picnic spot near Austin, the researchers said.

"They really weren't in the Waco area until right before they died, which is a little unexpected," the study's lead researcher, Don Esker, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Geosciences at Baylor University in Waco, told Live Science. "Two hundred kilometers is within the largest distance that we've known Columbian mammoths to travel, but only just." [Mammoth Resurrection: 11 Hurdles to Bringing Back an Ice Age Beast]

Esker and his colleagues made this discovery by studying the isotopes (an isotope is a variation of an element that has a different number of neutrons in its nucleus) in the mammoth's teeth. So far, Esker has studied just one tooth, but he has plans to examine more teeth from different mammoths in the coming months.

Esker could have a lot of work in front of him. There are remains from at least 23 mammoths dating to the late Pleistocene in Waco. The prehistoric graveyard was found in 1978 by two local youngsters, Paul Barron and Eddie Bufkin, who were searching for fossils and arrowheads when they discovered the fossilized mammoth bones. In 2015, President Barack Obama issued a presidential proclamation, with bipartisan support, that made the site a national monument, according to the National Park Service.

It's likely, but not certain, that these fossils are from the same mammoth nursey herd, Esker said. His goal is to confirm whether these mammoths traveled together as a social group, and to learn where they traveled and what they ate, he said.

If his research reveals these mammoths gulped down the same kind of water and gobbled up the same types of food, then it's likely they did travel as a herd, he told Live Science here at the 2017 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mammoth menu

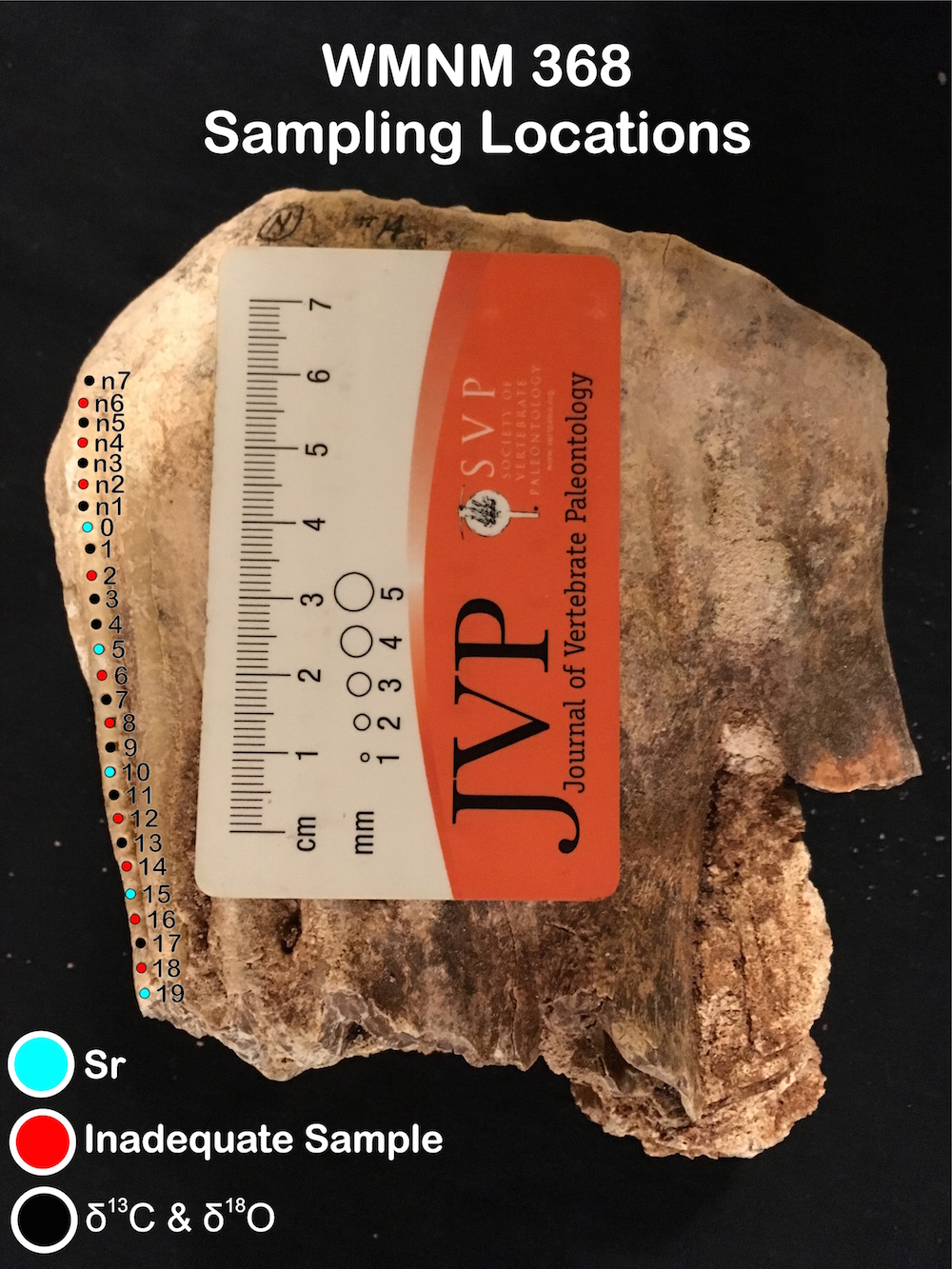

To get started, Esker analyzed the carbon, oxygen and strontium ratios in a single mammoth tooth, which helped him reconstruct "an itinerary and menu for the mammoth over the last six years of its life," he said.

When mammoths dined on vegetation, the plants' nutrients eventually ended up in their teeth. This information can reveal what types of plants the mammoths ate, because the way plants photosynthesize energy from the sun governs what type of carbon isotopes they produce: Carbon 4 (C4) indicates that the beasts ate grasses and sedges, and carbon 3 (C3) shows that they ate most other vegetation, including honey locust, Osage orange and mesquite.

"The carbon told us that the mammoth in question ate 65 percent to 75 percent warm season C4 grasses year-round," Esker said. This supports evidence from mammoth fossilized poop, or coprolites, that also revealed that Columbian mammoths ate plants containing C4.

Meanwhile, the oxygen isotopes in the mammoth's tooth showed that conditions "may have been a good deal more arid than [they are] today," Esker said.

Finally, the strontium isotopes revealed that the mammoths "spent a good deal of time eating grass growing on granite-derived soil," Esker said. The only place Esker could find with this type of soil was west of Austin, he said.

In addition to studying mammoth teeth, Esker and his colleagues plan to analyze chompers from a horse, camel and pronghorn that also perished at the Waco site. The results will show whether these animals' ranges overlapped with the mammoths' stomping grounds, Esker said. [Photos: Mammoth Bones Unearthed from Michigan Farm]

"Serially sampling teeth for isotopic analysis can be unpopular, as it does cause slight damage to the fossils," Esker said. "Nevertheless, it is an unparalleled record of an animal's life, and has much to offer us."

The research, which has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, was presented Wednesday (Aug. 23) at the 2017 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.