Harvey vs. Katrina: How Do These Monster Storms Compare?

Tropical Storm Harvey's historic rainfall and flooding continue to batter the Texas coast near the Gulf of Mexico, and Louisiana's southwestern coast is bracing to similarly face an onslaught of heavy rainfall and rising floodwaters in the coming days.

With significant rainfall and flooding still in the forecast, Harvey could rival the devastating impact of Hurricane Katrina, which pummeled the Louisiana coast in 2005 and was one of the deadliest storms to ever strike the U.S. It caused 1,833 deaths and cost about $108 billion in damages, according to the National Weather Service (NWS).

What shaped these two catastrophic events, and how do they measure up against each other? [In Photos: Hurricane Harvey Takes Aim at Texas]

Harvey made landfall in Texas on Friday (Aug. 25) at 11 p.m. local time as a Category 4 hurricane, with maximum wind speeds surpassing 130 mph (209 km/h), The Washington Post reported. Later downgraded to tropical storm status, Harvey has since deposited more than 20 inches (51 centimeters) of rain in regions of southeastern coastal Texas, according to the National Hurricane Center (NHC).

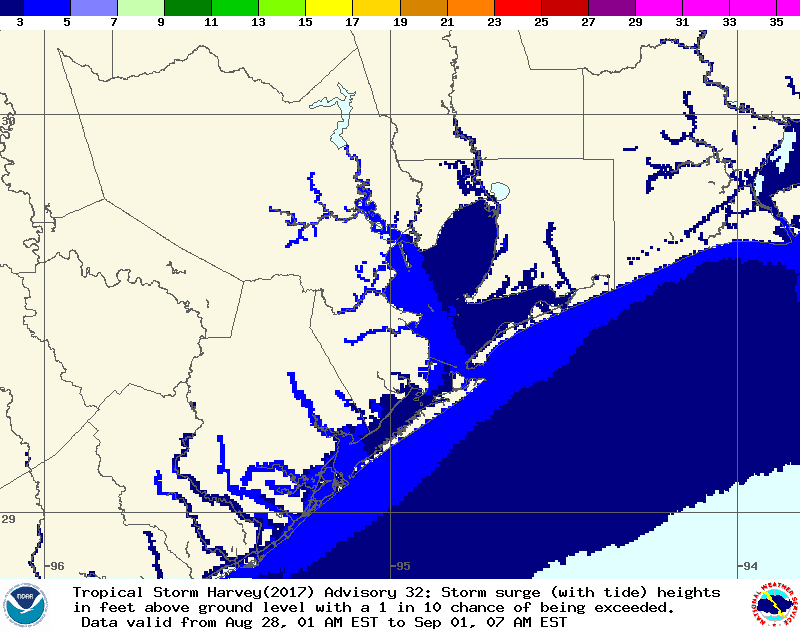

In the Houston area alone, reports estimate nearly 30 inches (76 cm) of rain have fallen over two days, NHC officials reported, and life-threatening flooding is underway across inland areas in south-central Texas, with storm surges of up to 5 feet (1.5 meters) anticipated in some areas, according to the NWS. At least eight people have been killed and more than a dozen injured thus far, The Washington Post reported.

Birth of Katrina

Katrina formed as a tropical storm in the Bahamas on Aug. 24, 2005, first impacting the Florida coast on Aug. 25 as a Category 1 hurricane, then making landfall in southeastern Louisiana on Aug. 29 as a Category 3 storm, with sustained winds of 120 mph (193 km/h). Rainfall totals during Katrina were significantly less than those during Harvey — between 6 and 9 inches (15 and 23 cm) on the Mississippi coast, and around 5 inches (13 cm) or less in northern Mississippi into Ohio, according to NASA's Earth Observatory.

Accompanying Katrina was a massive storm surge — an abnormal rise in coastal sea levels, generated by storm activity — with waters cresting at heights of 10 to 25 feet (3 to 8 m), which more than made up for the hurricane's relatively low rainfall. Floodwaters inundated coastal Mississippi and southeastern Louisiana, leaving 80 percent of New Orleans under water that was slow to drain and lingered for weeks. [A History of Destruction: 8 Great Hurricanes]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It is still too soon to tell the extent of Harvey's storm surge, which is difficult to measure in real time while a storm is in progress, Michael Lowry, a scientist with the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research — a nonprofit consortium dedicated to the study of atmospheric science — wrote in a tweet on Aug. 26. In fact, scientists might need weeks to calculate Harvey's storm surge, Lowry added.

The staggering amount of rainfall that Harvey is expected to deliver — an estimated 50 inches (127 cm) in some areas — can be explained by the condition of wind currents that held the storm system in place over southeastern Texas, Jason Runyen, a forecaster with the NWS in Austin/San Antonio, told Live Science.

"Harvey ended up stalling over south Texas for about 12 to 24 hours," Runyen explained. The storm's slow movement meant that bands of heavy rainfall remained in place, leading to the catastrophic flooding currently submerging homes, businesses and roads, Runyen said. Katrina, which traveled steadily across Louisiana and Mississippi, didn't have the opportunity to deliver soaking rains in massive quantities, he said.

Hurricanes and tropical storms are propelled along by large wind patterns in the atmosphere, much as river currents carry objects such as leaves or branches, Runyen told Live Science. But rivers can also contain still regions that are outside the reach of smaller currents and eddies. If a leaf is carried into one of those quiet areas, it'll stay there — and the same can happen to storm systems that move beyond the reach of strong air-current patterns, Runyen said.

An event similar to Harvey occurred in June 2001, when the tropical storm Allison stalled over southeastern and eastern Texas for days, soaking Houston with up to 40 inches (102 cm) of rain, Runyen explained.

Not over yet

Harvey is still underway, which means the full extent of its impact is yet to be seen. The storm is now moving southeast toward the Texas coastline, but will be looping back to make a second landfall in southeast Texas on Wednesday (Aug. 30), the NWS announced Monday morning. Extended rainfall is expected through Wednesday — as much as 15 to 25 inches in some areas, according to an advisory issued yesterday (Aug. 28) by the NHC.

"There's still a heavy rainfall threat in southeast Texas, and catastrophic flooding is ongoing," Runyen told Live Science.

And the effects of river flooding in the region will linger after Harvey dissipates, taking days or even weeks to drain back into the Gulf of Mexico, Runyen added.

Currently, life-threatening flooding persists across southeastern Texas, according to the NHC, and residents are warned not to attempt to travel in affected areas, and to avoid driving on flooded roadways.

The link between climate change and more frequent, "historic storms," such as Harvey and Katrina, is indisputable, scientists have said. Tropical storms and hurricanes are part of Earth's natural climate processes, but rising ocean temperatures are helping to fuel more-powerful storms, while elevated sea levels increase the risk of dangerously high storm surges in coastal cities.

If climate change continues unchecked, more of these intense hurricanes can be expected over the next century — along with more droughts, heat waves and other extreme weather events worldwide, according to a report published in 2011 by the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.