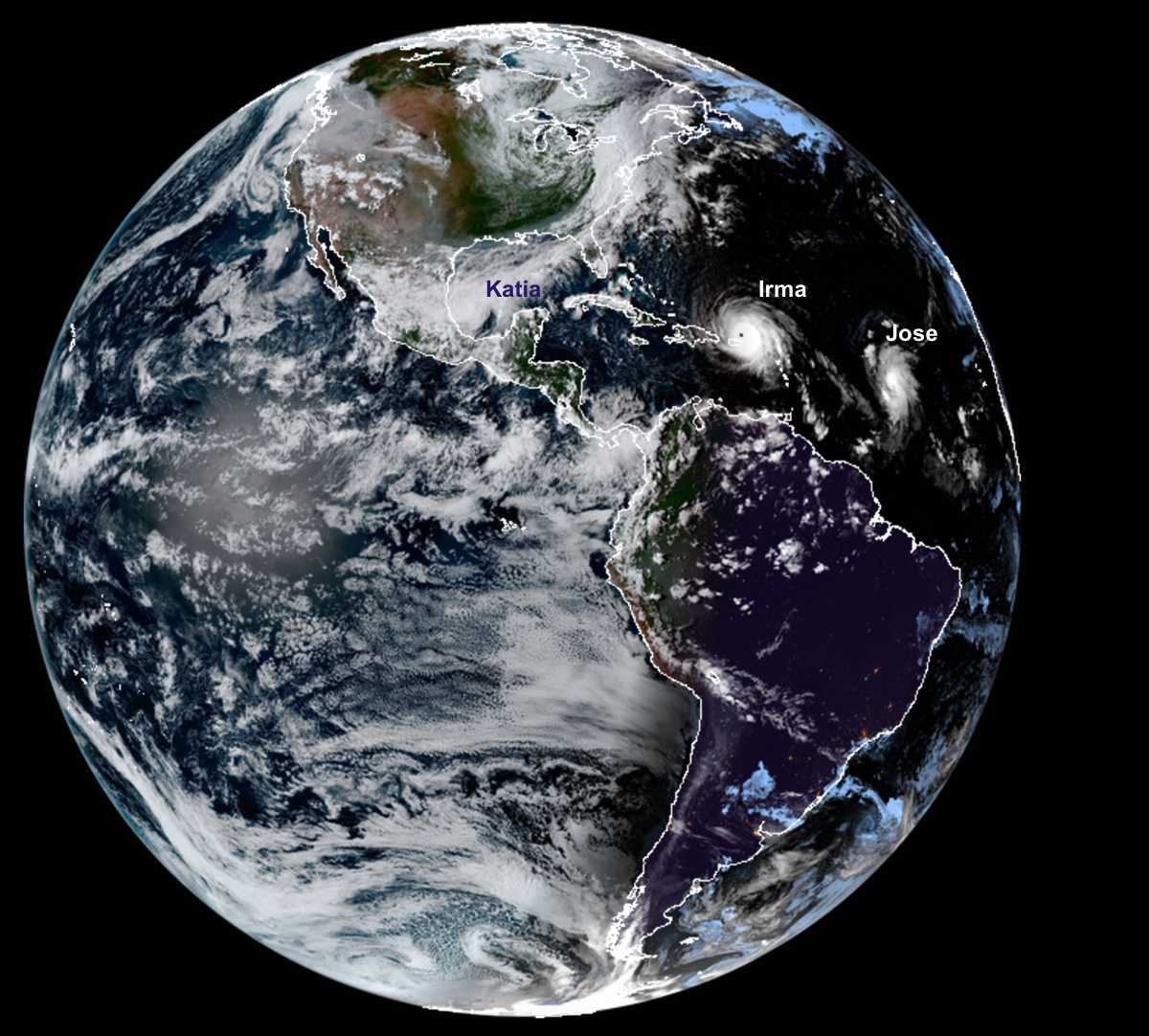

Right now, three hurricanes are churning in the Atlantic — Hurricane Irma, Hurricane Jose and Hurricane Katia.

While that may seem like a freak occurrence, it turns out that this hurricane-palooza is a predictable result of clear climate patterns, and an event that happens about once every 10 years, experts say. This year, it may simply be more noticeable because at least two of the monster storms are likely to batter population centers, experts say.

"It's not a random chance at all. Hurricanes aren't really a random phenomenon. They need conditions that are very conducive in order to form," said Gerry Bell, a lead seasonal hurricane forecaster with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center. "We had predicted that it would be an active season." [Hurricane Irma: Photos of a Monster Storm]

Two large-scale weather patterns in the Atlantic tend to govern whether a hurricane season is active or not, and this year, both patterns lined up perfectly to create hurricane-friendly conditions, Bell told Live Science.

When these two climate patterns align, they produce the fuel that hurricanes need, said Phil Klotzbach, an atmospheric scientist at Colorado State University.

Three ingredients for hurricanes

Hurricanes need three elements to get going: warm water, moisture in the atmosphere and low wind shear, or the change in wind speed with increasing height in the atmosphere.

The warm water provides the energy for fueling the cyclones, while the atmospheric moisture at low levels is needed to pull in moisture. Finally, if the wind shear is low, that means the perfectly symmetrical shape needed for a whirling hurricane can form, Klotzbach said. High shear disrupts wind circulation by tilting the storm and breaking it up, he added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This year, the Florida Straits are like jet fuel for hurricanes, at a balmy 90 degrees Fahrenheit (32 degrees Celsius), Klotzbach said.

Huge weather patterns

Two large-scale patterns govern how active an Atlantic hurricane season will be: the El Niño /La Niña cycle, which can vary from year to year, and the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation (AMO), which is an overarching weather pattern that flips every 25 to 40 years.

An El Niño year means warmer waters in the tropical Pacific, which creates stronger winds in the Atlantic Ocean, Klotzbach said.

"It gives too much wind for storms to really ramp up," Klotzbach said.

La Niña years, meanwhile, tend to fuel calmer winds in the Atlantic, he said.

The AMO has both a warm phase and a cool phase. In the warm phase, the ocean temperatures are warmer in the Atlantic Ocean, the wind shear tends to be weaker, the winds coming off Africa tend to fuel more hurricanes and more moisture comes off the Atlantic Ocean, Bell said. There is also more atmospheric instability, or the ability for air to move upward in the atmosphere, which can seed hurricanes, he added. The AMO's cool phase suppresses hurricanes; for instance, between 1971 and 1995, during the AMO's cool phase, just two active hurricane seasons occurred, Bell said.

Though the hurricane pattern varies from year to year, we've been in a warm, or more active phase since roughly 1995, Bell said. It's not exactly clear why this large-scale pattern fluctuates every few decades, although it has something to do with the North Atlantic gyre, a conveyer belt of ocean current currents that wends between Iceland and the equator. Either way it's a clear pattern that's been noticed since the 1880s, Bell said.

Sept. 10 is the peak hurricane day, when, statistically, all these conditions are likeliest to come together to produce hurricanes. So, this year's trio of cyclones isn't far off from the most active time of the year, statistically speaking. In general, favorable hurricane conditions tend to peak in August, September and October, Bell said.

No clear link to climate change

Climate change may contribute to sea level rise, which can worsen storm surge height. But it's not clear this year's busy hurricane season itself can be attributed to climate change, Klotzbach said.

"It's a more nuanced process," he said.

The Atlantic Ocean is certainly warmer than average this year, but, by definition, some years will be warmer or colder than the average, so it's impossible to say with confidence that warm waters are due to climate change, Klotzbach said. And though warmer waters do fuel more hurricanes, they may also produce warmer air in the atmosphere, so the overall effect on the atmospheric stability isn't clear, he added.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.