With the buzz saw of Hurricane Irma zooming ever closer to Florida, the state has issued evacuation orders for about 5.6 million people, one of the largest evacuation orders the country has ever seen.

The evacuation orders covered several counties and about a quarter of Florida's total population. Already, gridlock turned some interstate highways into parking lots, and gas shortages plagued many areas, ABC News reported. Hotels in nearby states are filling up, and hundreds of makeshift shelters are being hastily assembled for those who have no place to go during the storm.

But how is it possible to evacuate so many people safely?

It turns out that the key is just a lot of preparation and planning, said Susan Cutter, director of the Hazards and Vulnerability Research Institute at the University of South Carolina.

"This is a very-well-thought-out and systematic process of planning for getting people out of harm's way and then planning for the re-entry of people, and there's a lot of science behind it," Cutter told Live Science. "It's not just something that's done willy-nilly."

Related:

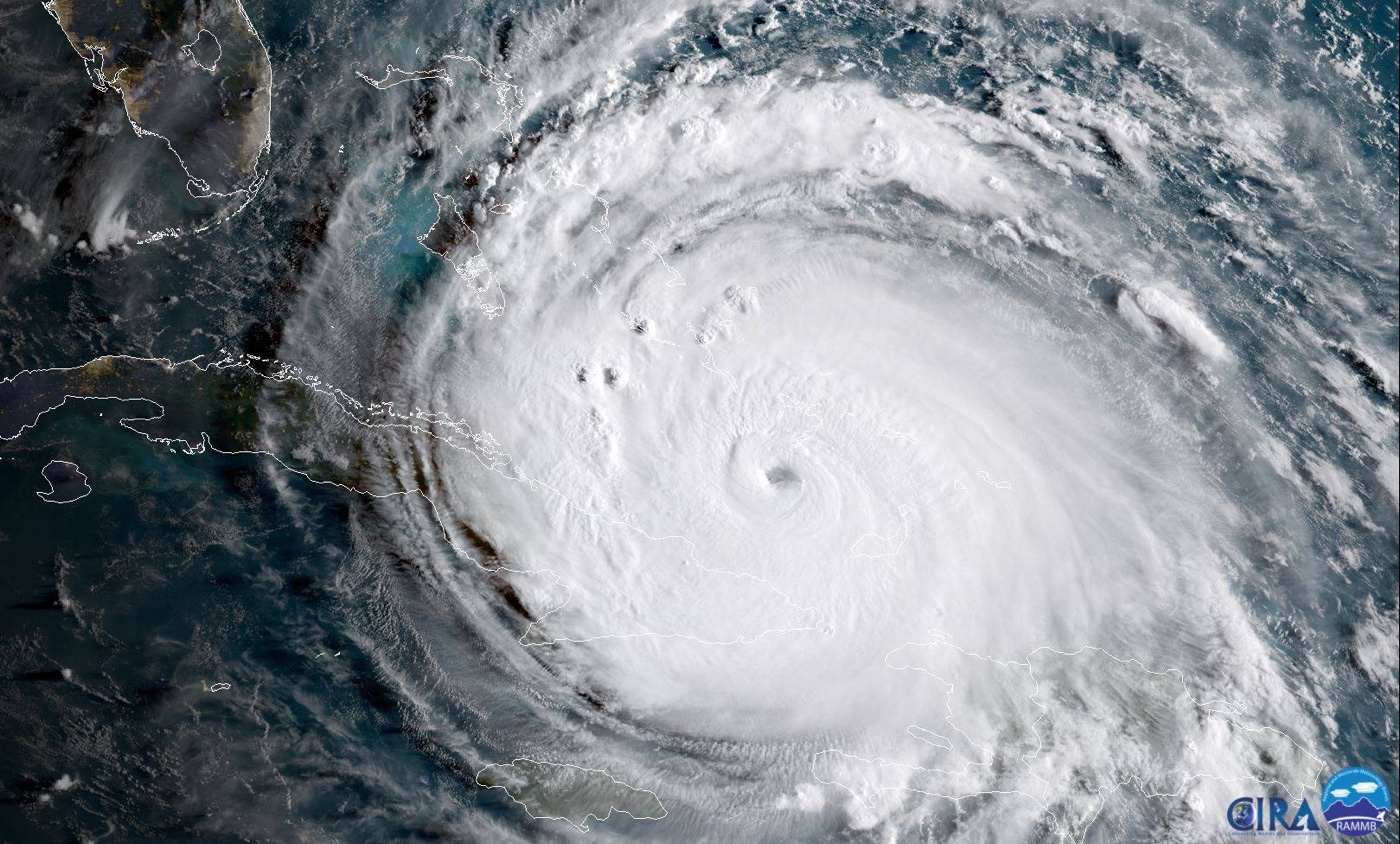

- Hurricane Irma Photos: Images of a Monster Storm

- Where Will Hurricane Irma Make Landfall on the Florida Peninsula?

- Hurricane Irma: Everything You Need to Know About This Monster Storm

Whether to evacuate

The question of whether to evacuate is not always clear-cut, as Hurricane Harvey revealed just a few weeks ago. However, cities like Miami, and counties in Florida, have been thinking about and planning for major hurricanes for a while, Cutter said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The key to getting people out of a hurricane's way safely is figuring out exactly how long it takes people to leave an area based on the local road networks, called the clearance time; figuring out exactly which areas are at risk of hazardous conditions; and factoring in the arrival of tropical-force winds, or those greater than 39 mph (63 km/h). Hurricane Irma is a huge, Category 4 monster, with tropical-storm-force winds extending out 185 miles (295 km) from its center, meaning people need much more lead time to get out safely than might otherwise be necessary. [WATCH: Harrowing Flight into Irma Captured in Time-Lapse Video]

"You don't want cars on the road in that kind of wind, and you certainly don't want cars going over bridges from barrier islands to the mainland in that kind of wind," Cutter said.

Using data from traffic modeling, population data and flooding/storm-surge hazard data, emergency planners might calculate that, say, evacuating the Florida Keys requires 24 hours, and that tropical-force winds might arrive 36 hours before the eye of the hurricane hits, meaning the evacuation needs to commence 60 hours before the storm-surge risk peaks, Cutter said. In that example, that may mean evacuating before the hurricane warning or storm-surge warning is officially out, based on the lead time that the National Hurricane Center provides (typically 48 hours for a hurricane watch or warning, and less time for storm-surge warnings).

Reducing chaos may also involve early action by local organizations. Areas that could possibly be affected may know considerably earlier than official National Hurricane Center watches or warnings are issued. So many organizations, such as universities, preemptively closed a few days ago, meaning many people already had time to leave town, Antonio Nanni, a structural engineer at the University of Miami, previously told Live Science.

To mitigate the probem of gridlock, emergency planners have set up evacuation route and zone maps for each area in Florida, which are based on detailed studies that account for everything from vacant housing, to flood risk, to the demographics of vulnerable populations, to block-by-block land use. The Florida Department of Transportation also has a hotline that callers can use to identify the best way out of the area. (That number is (850) 414-4100 or (toll free) (866) 374-FDOT (3368)). FL511.com also has information on evacuation routes. And Gov. Rick Scott has set up a separate hotline to help people who are trapped in gridlock so that they can get out of the path of the hurricane in time.

Gas shortages are another problem, but in this instance, Florida has initiated a state of emergency, which has helped prevent the price gouging that can lead to gas shortages, ABC News reported.

Small moves

While the reach of Irma's punishing winds may be huge, the actual areas that must be evacuated are considerably smaller. In general, most people will be moving small distances, away from the coasts inland, and then from the inland areas north in Florida. There's no need in a hurricane to relocate to Virginia or New Jersey, clogging up interstate highways, Cutter said.

In South Florida, evacuation zones on storm-surge planning maps are separated into concentric rings of A through E, with areas in evacuation zone A being those along the coast at the greatest risk of flooding and inundation, according to Florida planning maps. Not all the zones are required to evacuate. Areas aren't typically evacuated for winds (basically all of Florida is going to be subject to high winds). Building codes are supposed to mitigate wind damage. So the only people who should be evacuating due to wind are people who are in vulnerable structures and are moving to sturdier ones, Cutter said.

As long as someone has a safe place to travel to that can withstand hurricane-force winds, it's possible that many people living in evacuation zone A may not necessarily have to go to another city or state in order to stay safe, said Nanni, who on Wednesday was planning to ride out the storm in his own home, which is in the most hazardous evacuation A zone but had a plan move to a safer spot just a few miles away if the weather forecast necessitated it. Instead, they can go somewhere within the same city or general region.

The vast majority of people will either bunk up with family and friends or flood the local hotels.

"They just feel more comfortable in the hotels and motels or with family and friends," Cutter said.

However, the most vulnerable populations — those without a strong social network and without a lot of financial means — will need shelters. Those sites (often schools) are predetermined in advance by the Red Cross based on the threat of flooding, the structures' wind resistance, the availability of sanitary facilities like restrooms and showers, and food prep facilities or room for food prep tents, Cutter said. In addition, population modeling needs to predict the number of people who will seek shelter, which is based in part on past data and in part on the local populations.

So far, hundreds of shelters have been set up; people who have nowhere else to go can use these shelters and should head to the closest one to them. They are likely to fill up fast, according to officials from state and local agencies. (The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has a list of shelters for those under evacuation orders.)

Shadow evacuation and vulnerable populations

In any evacuation, about 10 to 20 percent of the people fleeing are choosing to do so voluntarily but are not in the evacuation zones. They may not be in direct damage of life and limb but may simply conclude that it will be too hard to stay in the affected area during and immediately after the storm, Cutter said.

"That's a phenomenon that we call a shadow evacuation," Cutter said.

So planners need to account for that extra traffic on roadways and that extra demand on hotels and motels, housing and shelters, Cutter said.

Vulnerable populations, such as those in medical centers who may need electricity to keep them alive, are often evacuated earliest in the process, Cutter said. The homeless population is tricky, because they are hard to find. However, emergency agencies typically work with local homeless coalitions to help identify those in need and to try to convince them to leave the streets. That can often be a difficult task, Cutter said. In Florida, there is a law, called the Baker Act, that among other things, allows for involuntary placement of people in the homeless population into care facilities temporarily during an emergency like a hurricane. [Inside Irma's Eye: Hurricane Hunters Capture Jaw-Dropping Photos]

Other vulnerable populations include those who do not speak English and thus may need local agencies to specifically target messages to them to help them get out, Cutter said. And some people may not have cars, so bus routes and shuttles need to be set up and publicized so people without cars can safely evacuate, she added.

Staying put and coming back

Those who are staying put should be aware that even if their local area is unaffected, they could be cut off from major services like water and electricity for a while. And though emergency rescue workers are prepositioned in areas outside the evacuation zone, they will have problems reaching people after the storm passes, because downed trees, debris and downed power lines will clog the streets, and that will take time to clear. So they need to be prepared to sit things out. [Hurricane Preparation: What to Do]

"You need to have a lot of patience," Cutter said.

People who are staying in their homes need to have at least a gallon of water per person (plus pets) for at least three to five days, though likely more. They need several days' worth of food that doesn't require refrigeration because power will certainly go out, cash because ATM machines won't work, medical supplies, medicines and first aid kids, a full tank of gas, and identification and essential documents in waterproof plastic bags, Cutter said.

Often, people will survive the initial hurricane unscathed but may injure themselves while, say, moving lumber or stepping on a nail, and they need to have supplies to deal with minor injuries and identification in case they need more serious help, she said.

Residents will not be allowed to re-enter the impacted areas until search-and-rescue teams have ensured everyone is accounted for, Cutter added.

"There will be a delay in getting people to re-enter and start their own individual cleanup," Cutter said.

While shadow evacuation may increase demands for roads and shelter, the biggest issue are those, like people in the Florida Keys who plan to "ride out the storm," who simply don't heed the mandatory evacuation orders (which are ultimately voluntary and not enforceable), Cutter said.

"They've also made a risk calculus and said 'No, I'll be fine,'" Cutter said. "Well, the science suggests that no, you're not going to be fine, but we'll hope for the best."

Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.