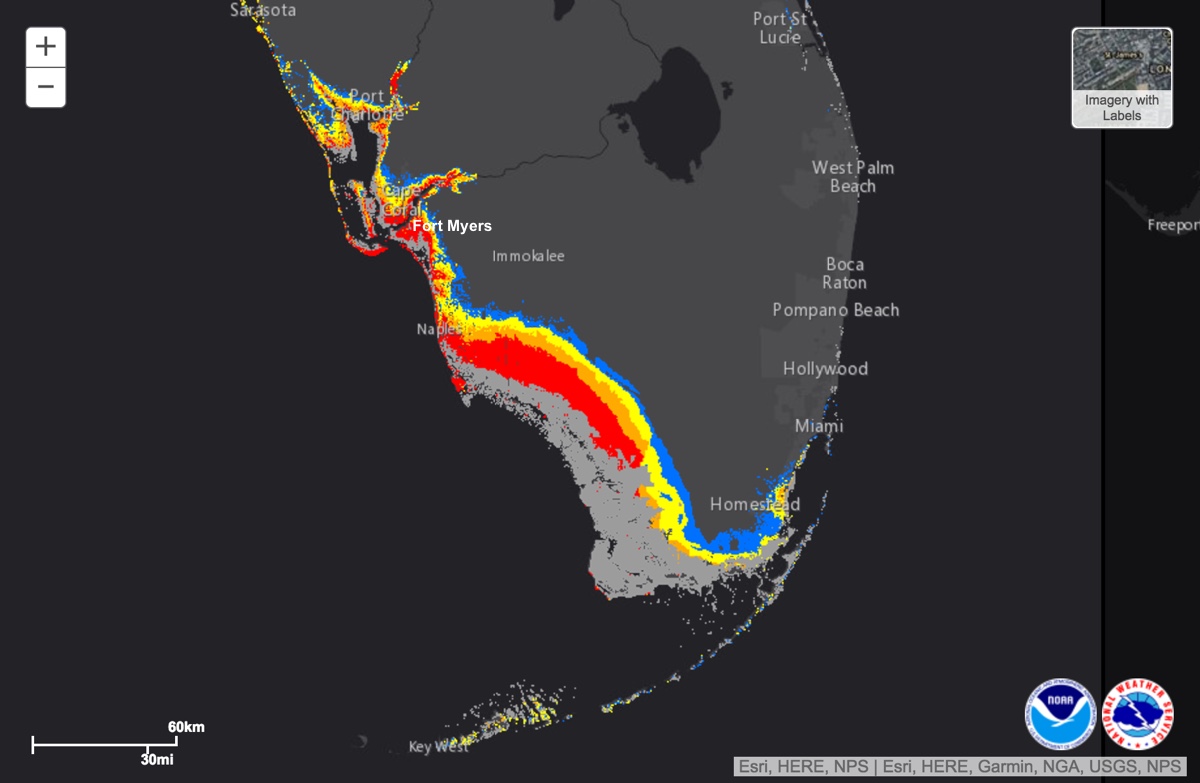

Hurricane Irma: Biggest Storm Surge Threat Along Florida's Southwest Coast

As the forecasted path of Hurricane Irma has shifted westward over the past couple of days, so has the biggest storm-surge threat. Southwest Florida is now staring down the barrel of a surge of up to 15 feet (4.6 meters). But the rest of Florida isn't getting away scot-free, with prolonged surge still expected along the east coast of the state.

There's also the potential for rain to exacerbate surge flooding — or flooding that results from water being pushed ashore by the hurricane — from the Keys to Georgia's coast.

The Florida Keys are first in line as Irma pulls away from the coast of Cuba as a Category 3 hurricane.

The archipelago faces a double whammy of surge as the storm moves through, said William South, a tropical weather meteorologist at the National Weather Service's (NWS) Key West office. As Irma approaches from the southeast, its winds will be hitting the islands from the northeast, pushing water toward the Keys from Florida Bay and the nearshore Gulf of Mexico. But as the storm gets closer on Sunday (Sept. 10) morning, "the winds will abruptly turn to the south," bringing in surge from the Atlantic, he told Live Science.

RELATED:

- Hurricane Irma Photos: Images of a Monster Storm

- Where Will Hurricane Irma Make Landfall on the Florida Peninsula?

- Hurricane Irma: Everything You Need to Know About This Monster Storm

- Hurricane Irma: How Do You Safely Evacuate 5.6 Million People?

That surge, which is expected to reach 5 to 10 feet (1.5 to 3 m), according to the National Hurricane Center, will be exacerbated by large, bruising waves, South said. (Storm surge measurements indicate the amount the water will rise above the normal tide level.)

The last time the Keys faced a situation like this was Hurricane Donna in 1960, he said. Donna hit as a Category 4 storm and caused storm surge of up to 13 feet (4 m) in the Keys, according to National Weather Service records.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The heavy rain expected in the Keys — isolated amounts of 25 inches (63.5 centimeters) are possible, according to the NHC — could exacerbate the surge flooding. When Hurricane Katrina passed over in 2005, the Keys got 10 inches (25 cm) of rain, "and that was a major flooding even without really any storm surge threats at all," South said.

Naples, Fort Myers and Tampa

The biggest surge threat right now is along the southwest coast of mainland Florida, including the Naples and Fort Myers areas.

The waters off the west coast of Florida are shallow, which allows the surge to build up. From the southwest tip of the state up to the Fort Myers area could see 10 to 15 feet (3 to 4.5 m) of surge, according to the NHC. From north of Fort Myers to South of Tampa could see 6 to 10 feet (1.8 to 3 m), and the Tampa area could see 5 to 10 feet (1.5 to 3 m).

As the storm moves parallel to the coast, areas will first see waters moving away from the coast — called negative surge — because Irma's winds will be blowing offshore, said Rick Davis, a meteorologist with the Tampa Bay NWS office. This will be particularly noticeable in Tampa Bay, where mud flats could be exposed, said Hal Needham, founder of Marine Weather and Climate, a private company that helps communities improve resiliency against coastal hazards.

But as the storm passes to the north and the winds shift onshore, "then you're going to have a very rapid surge that's going to come in," Davis told Live Science.

Some of the hardest-hit areas will be those aligned with the winds, such as Captiva Island, off the coast of Fort Myers, as well as downtown Tampa. Captiva is "a narrow island, and it faces due west," so when the storm's winds swing around to come from the west, it will face its highest surge risk.

Likewise, winds from the southwest and west will push waters on the northeast side of Tampa "pretty much where downtown Tampa is" and where cruise terminals are located, Davis said.

Timing will also be an issue with Irma's surge, as the biggest inundation won't coincide with the highest winds. Forecasters and emergency managers are warning people in the region not to let their guard down after the strongest winds have passed, out of concern they could be surprised by the surge, which is also expected to coincide with a high tide in the middle of the night, at 3 a.m. local time, Davis said.

Florida's west coast

Surge will also be pushed up into rivers along the west coast of Florida, so "we could have flooding well up the river," he said. Heavy rains could also compound those river floods, with the surge preventing the rains from draining into the Gulf of Mexico.

From Cedar Key north through St. Marks (in the Tallahassee area), or the bend in Florida's west coast, a so-called shelf wave could develop, Needham said. "Sort of a shelf of water gets trapped between the storm and the shelf" and is "really extremely efficient for storm surge," he said.

The storm-surge threat has diminished on the east coast, but it's still a threat and will be prolonged as onshore winds are followed by winds pushing up water from the south as Irma churns northward.

Florida's east coast

The stretch of coast from Key Largo to North Miami Beach could see 4 to 6 feet (1.2 to 1.8 m) of surge, while the rest of the coast up to the Georgia border could see 2 to 4 feet (0.6 to 1.2 m).

Needham is concerned about the combined threat of rain and surge along the Georgia coast. Even though the surge is expected to be relatively small there, its prolonged nature could prevent heavy rains from draining away, he said.

Some enhanced flooding could happen in downtown Jacksonville, Florida, as southerly winds push water up the St. Johns River, which is aligned north to south, said Jason Hess, a NWS meteorologist with the Jacksonville office. Where the river takes an eastward turn in the middle of the city, water could build up.

The coast near Jacksonville is also already vulnerable because of damage done last year by Hurricane Matthew's surge.

"There's an enhanced risk because the dunes and the beach system are weakened from Matthew," Hess said.

There is still some uncertainty about the exact track of the storm. If it makes landfall over the southern tip of Florida, that will decrease the surge risk for the west coast, though it won't change the impacts much for the east coast.

"It's really doing this tightrope walk, and even a 10-mile [16 km] shift in track can shift things a lot" along the west coast, Needham said.

Original article on Live Science.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.