Hurricane Irma Makes Landfall in Keys; Deadly Surge in Store for SW Florida

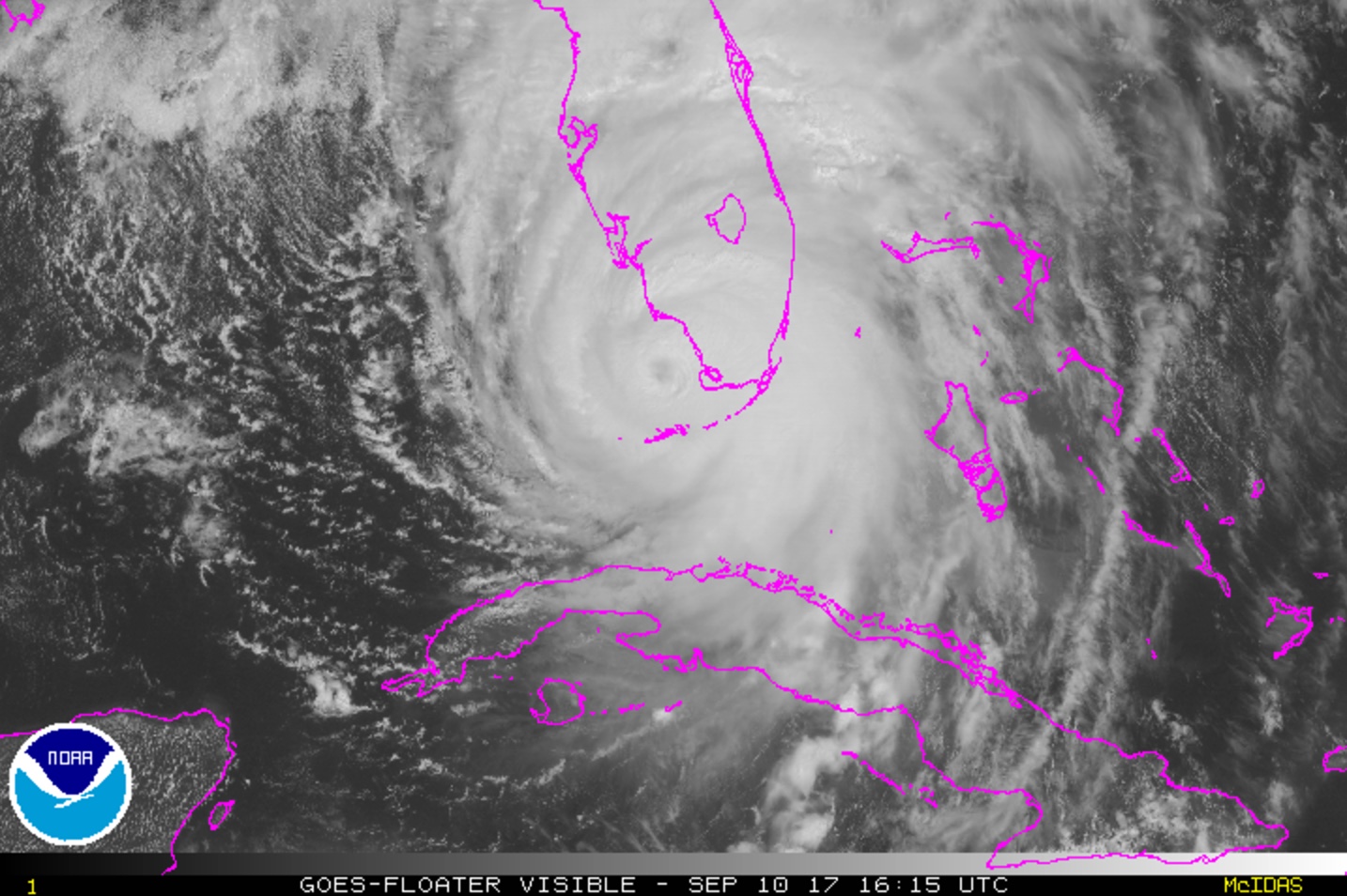

Hurricane Irma made its first U.S. landfall as a Category 4 storm in the Florida Keys Sunday morning (Sept. 10). This is the first year on record that two storms of that strength or higher have made landfall in the continental United States, with Harvey hitting Texas also as a Category 4 hurricane.

As Irma leaves the Keys and heads up along the west coast of Florida, it will cause catastrophic storm surge. The storm's relatively large size means it is also battering the east coast of the state, with punishing winds hitting Miami and pushing water into the streets between the high-rise buildings.

RELATED:

- Hurricane Irma Photos: Images of a Monster Storm

- Where Will Hurricane Irma Make Landfall on the Florida Peninsula?

- Hurricane Irma: Everything You Need to Know About This Monster Storm

- Hurricane Irma: How Do You Safely Evacuate 5.6 Million People?

Irma has already left more than 1 million customers without power across the state, according to news reports.

Irma remarkably hit the Keys exactly 57 years after Hurricane Donna, the last time the archipelago faced a storm this strong.

It is also remarkable to have such a strong storm make landfall again so soon after Harvey. As Steve Bowen, a director and meteorologist with the reinsurance firm Aon Benfield, pointed out on Twitter, just 16 days separated the two landfalls; before Harvey, it had been 4,323 days since the last major hurricane (Category 3 or higher) had hit the U.S. mainland. That was Hurricane Wilma, in 2005.

Irma spent Saturday night (Sept. 9) lashing the Keys with strong winds, storm surge and crashing waves. It made landfall at 9:10 a.m. EDT on Sunday at Cudjoe Key, about 20 miles (32 km) northeast of Key West. A wind gust of 120 mph (195 km/h) was reported at the National Key Deer Refuge on Big Pine Key as Irma passed over on Sunday morning.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The hurricane will keep pushing north, with its expected track taking it right along the coast. Places like Fort Myers, Naples and Tampa are in peril of very dangerous and high storm surge — up to 15 feet (4.6 m) — the likes of which haven't been seen there in more than a generation.

Heavy rain will exacerbate the flooding from the surge, especially where the surge pushes up coastal rivers.

As the storm approaches, its winds will blow offshore and pull water out of areas like Tampa Bay. Photos show this is already happening. As Irma passes, its winds will shift and send water rushing back in. Local officials are concerned because the worst surge won't coincide with the highest winds, leaving the possibility that people riding out the storm could think the danger has passed with the winds, only to be caught by surprise.

"This is a life-threatening situation," the National Hurricane Center warned in its forecast.

Irma is also lashing Florida's east coast, especially the Miami area, where wind gusts up to 100 mph (160 km/h) were expected. A wind gust of 94 mph (151 km/h) was recorded at Miami International Airport, according to the NHC. A National Weather Service employee captured the collapse of a construction boom and counterweight over a high-rise building in the city. High-rises get the strongest winds because winds increase with height from the ground.

Tornado warnings are also being sounded as the storm produces tornadoes and waterspouts.

Whether and where Irma makes landfall along the west coast depend on its exact track. The current forecast shows this could happen anywhere from around Naples to the panhandle. If Irma tracks closer to the coast, it could improve the surge situation, as it gives the storm a bit less space to work with to push that surge, Hal Needham, founder of Marine Weather and Climate, a private company that helps communities improve resiliency against coastal hazards, told Live Science.

The storm will gradually weaken as it moves northward and interacts with land and is exposed to higher wind shear, or the change in wind speed and direction at different levels of the atmosphere that can tear hurricanes apart.

By late Monday (Sept. 11), Irma will be a tropical storm over southwestern Georgia and southeast Alabama, and by Tuesday, it will have weakened into a tropical depression over the northern portions of those states.

Original article on Live Science.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.