Lost Language, Code or Hoax? Why the Voynich Manuscript Still Stumps Experts

The story was tailor-made for headlines: The indecipherable Voynich Manuscript that once stumped the best code breakers of World War II had finally been cracked, and it was a simple health-and-wellness guide for medieval women.

Or not.

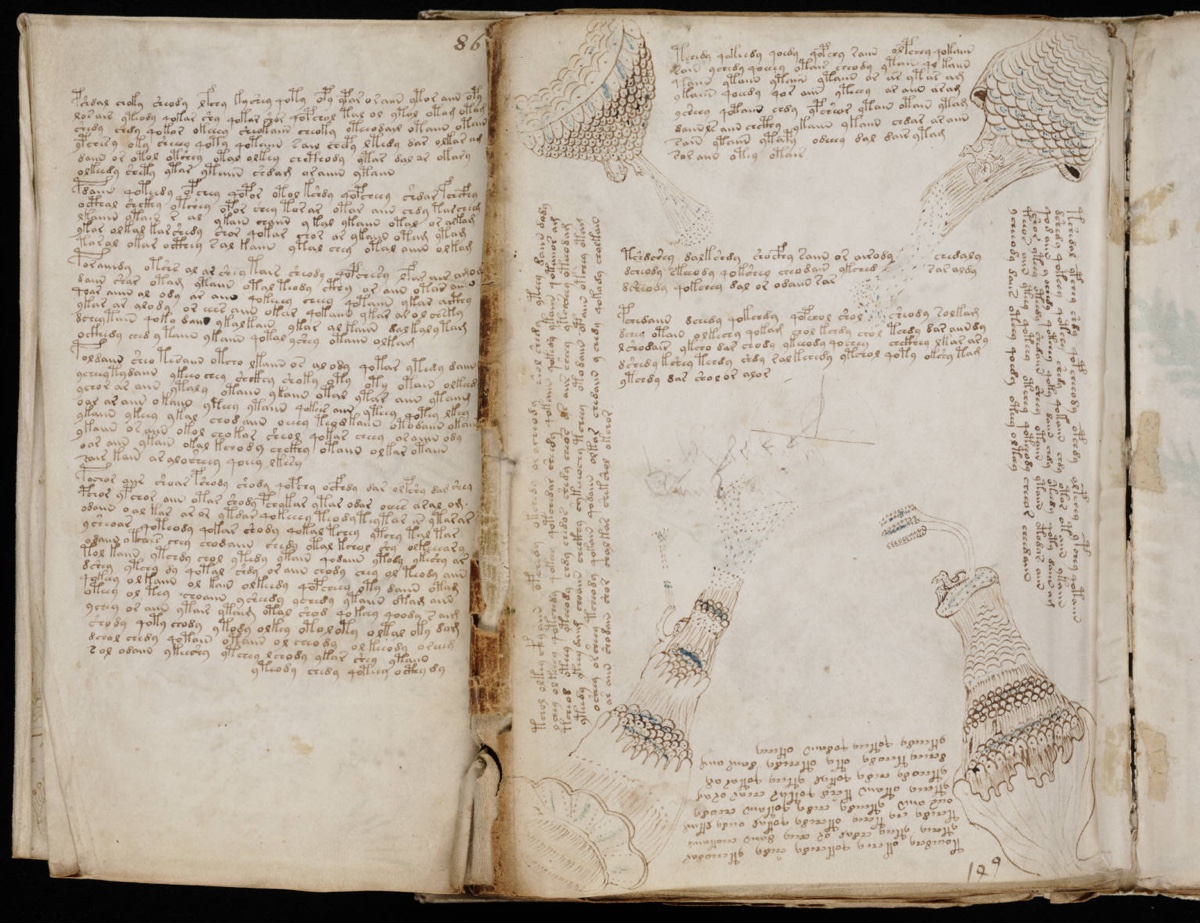

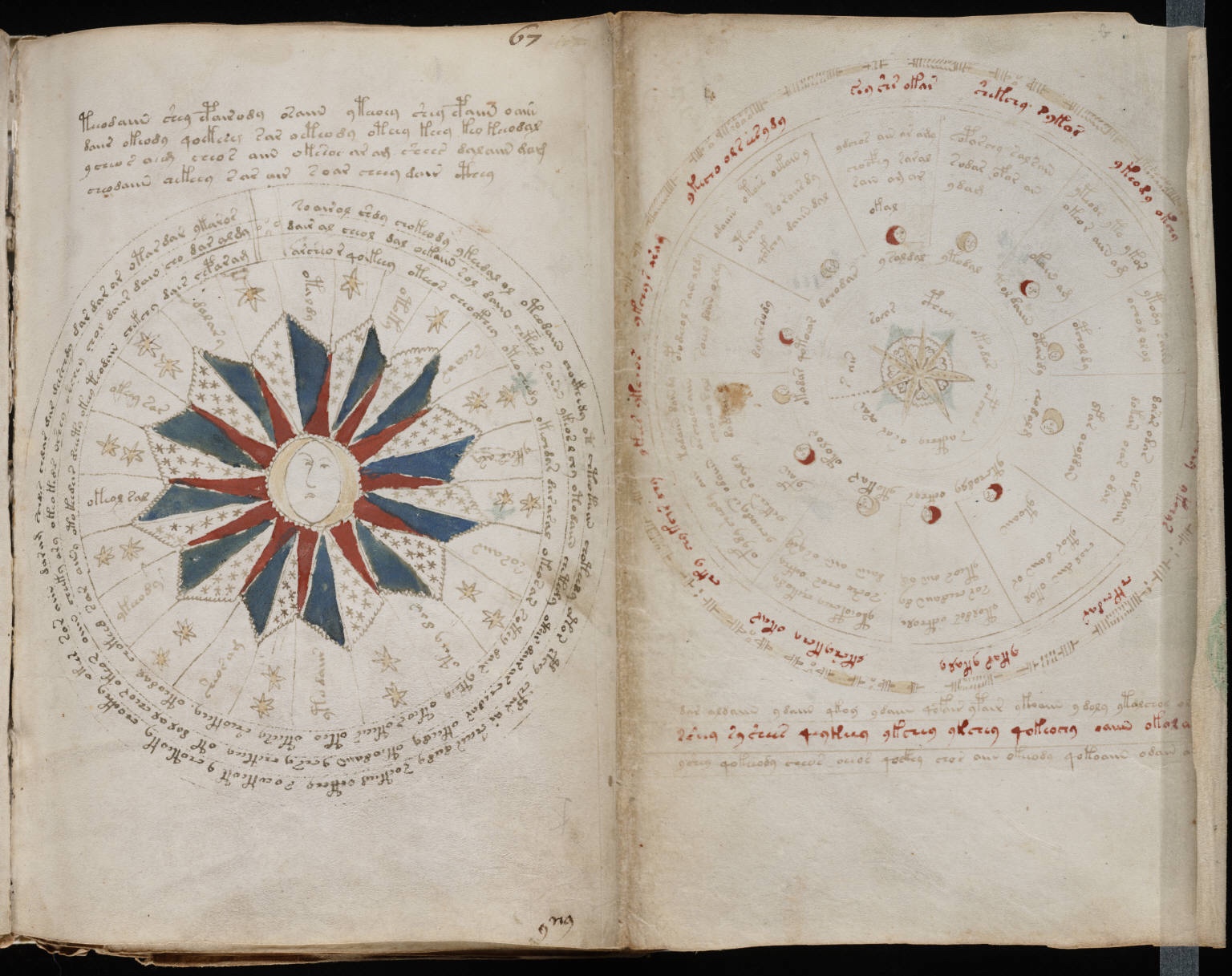

The Voynich Manuscript is a heavily illustrated book on parchment written in what looks like an unknown language. It's been the subject of intense debate ever since its acquisition in 1912 by antiquarian Wilfrid Voynich, who gave the manuscript its name. The parchment dates back to the early 1400s, but no one has ever managed to figure out what the manuscript says — or even if it says anything at all. [Voynich Manuscript: Images of an Unreadable Book]

For the latest theory, published Sept. 5 in The Times Literary Supplement, a researcher used the book's illustrations of herbs and bathing women, plus some speculations about the text deriving from Latin abbreviations, to suggest that it is a hygiene guide — sort of a medieval Selfmagazine geared toward upper-class women. But longtime experts in the manuscript quickly shot down this proposed theory.

"There's nothing," said René Zandbergen, an aeronautical engineer who runs a website about the infamous document and is well-acquainted with the various theories hobbyists have invented to explain it. "It's like some generic bits of possible history without any real evidence and then only two lines that really don't generate anything meaningful at all."

So if the latest Voynich media maelstrom is yet another dead end in the centuries of attempts to crack the manuscript, what is it about this bound stack of parchment that makes it so complex? Why can't experts even agree if the manuscript is a language or gibberish? And will we ever really know what was going through the mind (or minds) who put ink to paper to create this medieval marvel?

Lost language, code or hoax?

The fundamental problem with the Voynich Manuscript is that it inhabits a gray area, Zandbergen said. In some ways, "Voynichese," the nickname for the writing, acts as a language. In other ways, it doesn't. The fact that people have been trying to translate the manuscript since at least the 1600s to no avail could indicate that it's gibberish or a very, very good code. [Cracking Codices: 10 of the Most Mysterious Ancient Manuscripts]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What is clear is that the manuscript is truly medieval. The chain of ownership is fairly clear reaching back to the early 17th century in Prague, when the manuscript was owned by someone affiliated with the court of Habsburg emperor Rudolf II, Zandbergen said, and possibly by Rudolf himself. (It's held today at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University.) There are 240 pages in the manuscript, that, based on the illustrations, seem to be split into thematic sections: herbs, astronomy, biology, pharmaceuticals and recipes. Experts generally agree that the parchments are not a modern forgery; radiocarbon dating led by the University of Arizona places them firmly in the 1400s, and all of the parchments are the same age, suggesting they weren't cobbled together later and written upon. (However, given the uncertainties inherent in radiocarbon dating and the fact that the parchment may not have been used right after it was made, the text could have been written as recently as the early 1500s.)

The question is whether the medieval or early modern-era writer of the Voynich Manuscript was writing in a language, in code or in gibberish. The idea that the manuscript contains a forgotten or unknown language is the most far-fetched, said Gordon Rugg, a researcher at Keele University in the United Kingdom who has studied the properties of the manuscript's text and written about them in depth on his blog.

"This is clearly not a language," Rugg told Live Science. "It's just too different from all the languages in the world."

For instance, Rugg said, it's universally accepted that the most common words in a language are the shortest ones (think "a," "an" and "the"). That's not the case in the Voynich Manuscript. Nor do the patterns of words make much sense. In a typical book, words with meanings related to the illustrations appear more frequently near an illustration of those words. So in the Voynich Manuscript, plant words, like "root" and "stem," should show up more often on the pages about botanicals than on the other pages, Rugg said. And they should do so in particular patterns, so that color words, like "red" or "blue," appear in conjunction with the word "flower," for example. [Code-Breaking: 5 Ancient Languages Yet to Be Deciphered]

"There isn't a pattern like that" in the Voynich Manuscript, Rugg said. "All there is, is a bit of a statistical tendency for some of the words to be a bit more common on the plant pages than elsewhere, and that's it."

There are other oddities about the Voynich text that seem un-language-like, Rugg added. For instance, words at the beginning of lines are longer, on average, than words at the ends of lines in the book. That "doesn't make much sense" for a language, Rugg said. The distribution of syllables, which is typically the same throughout a text, is weirdly skewed in the manuscript. In addition, the manuscript doesn't have a single crossed-out or scratched-out word, Rugg said. Even the best scribes of the time made errors. If the manuscript is written in a language, it beggars belief that the person who wrote it never messed up, he said.

Code breakers

Option two is that the manuscript is a code based on a known language. This is what drew World War II-era code breakers to the Voynich Manuscript, Rugg said: They hoped they could crack the manuscript and use its secrets to develop new kinds of codes that would defy decipherment. That didn't work out.

In many ways, the Voynich Manuscript should make a terrible code, Rugg said. It has too much repetition and structure, which code-makers try to avoid because it can provide too many clues to code breakers.

Nevertheless, some researchers think the manuscript does contain a message. Marcelo Montemurro, a physicist at the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom, argued in a 2013 paper in the journal PLOS ONE that the word frequency in the manuscript looks language-like. In particular, the manuscript abides by Zipf's law, an equation that describes the relationship between the absolute number of times a word is used in a text and its rank on the list of how frequently words are used. The relationship, briefly, is a power law, meaning that a change in rank is always accompanied with a proportional change in absolute number of times used.

"If it's a hoax, it's so well done that it mimics the statistics of actual language," Montemurro told Live Science. "Which would be really odd, given that, at the time when the Voynich was conceived, no one knew anything about the statistical structure of language."

This opinion puts Montemurro and Rugg squarely in opposition. In 2016, Rugg published research in the journal Cryptologia that used a grid system of suffixes, prefixes and roots to quasi-randomly generate text that shares a lot of features with the Voynich Manuscript, including adherence to Zipf's law. Thus, Rugg argued, language-like features don't prove that the manuscript is a language.

Low-tech hoax?

If the Voynich text was created using Rugg's method, it would have involved filling out a grid with syllables in various frequencies that mimic those of real language. The creator might put the Voynichese syllable that looks like a fanciful "89" in every third box, for example, and then fill in other, rarer syllables every fifth box or every 12th box, nudging the syllables around here and there when they would otherwise overlap boxes. (Two of the same syllables would be side by side.) Next, the creator would take another sheet of paper with three holes cut out and move it over the grid, making words with the syllables that show through as he or she randomly moved the top sheet.

The trick to making the result look "real," Rugg said, is that this method is neither truly random nor strictly patterned. It's quasi-random. You can't "crack" the code or reverse-engineer the creation of the text because there are too many repetitions of syllables in the grids to ever be totally sure where the grid was positioned to develop any given word in the text, and too many fudged areas where the creator could have made a mistake or where he or she moved syllables around to prevent them from overlapping. But the method also produces patterns, including weird clusters of word lengths and frequency patterns that look language-ish. In other words, a truly random method would create no patterns in the text. A language or code would create much clearer patterns than Voynichese displays. But a quasi-random method could result in total nonsense that still looks patterned enough to fool people into thinking it's meaningful.

This grid method might seem a little laborious for creating a gibberish book, but code breaking had gotten fairly sophisticated by 1470 or so, Rugg said. If the book was written that late, which is possible, its creator would have known that stream-of-consciousness lettering would have been obvious as fake, while a quasi-random approach would look more convincing. It's also pretty mentally challenging to generate nonsense text page after page, Rugg said; the grid system would have actually been easier.

"I'm not saying it definitely is a hoax; I can't show that," Rugg said. "But what I can show is, you can produce text that has the quantitative and qualitative features of the Voynich Manuscript using low-tech, medieval technology."

Montemurro disagrees, arguing that Voynichese is still too complex to be explained by this quasi-random method. (Other critics have argued that the table-based method Rugg used was historically unlikely.) In the contentious history of the manuscript, it's another standoff.

Why make a manuscript?

Some Voynich experts have lost interest in the translation itself and have become more interested in the document as a phenomenon. [10 Historical Mysteries That Will Probably Never Be Solved]

"There's not going to be big secrets in there," Zandbergen said. What piques his interest is how the manuscript was made, not what it means.

In that sense, the people puzzling over the Voynich Manuscript are puzzling over human weirdness — likely just one person's weirdness, at that. The manuscript could have been conceived for any number of reasons. Perhaps its creator really was a supergenius who invented a new language or code that breaks every known rule of each. Perhaps it was a private language, Zandbergen said, or maybe the book was made to prove the creator's cleverness as part of an application for one of the numerous secret societies that flourished in the late Middle Ages, he added.

Or perhaps it was a hoax. If so, the hoaxer simply might have been out for cash, Rugg said. A book like the Voynich Manuscript could have fetched a pretty penny as a curiosity in the medieval or early modern era, he said, perhaps the equivalent of a skilled workman's annual salary.

Or maybe the motivation was personal. Hoaxers sometimes enjoy the thrill of pulling the wool over everyone's eyes, Rugg said. Or they may target their prank toward a particular person. In 1725, for example, the colleagues of University of Würzburg professor Johann Bartholomeus Adam Beringer planted a series of carved limestone "fossils" to fool Beringer into thinking he'd discovered something carved by God himself. Eventually, the hoaxers admitted in court that they wanted to bring the "arrogant" Beringer down a notch.

Sometimes, hoaxers are just hobbyists who want to make something beautiful, Rugg said. Other times, they believe their own stories. The 19th-century French medium Hélène Smith, for example, claimed to be able to channel the language of Martians. A 1952 book by psychologist D. H. Rawcliffe, "Occult and Supernatural Phenomena" (Dover Publications), examined her case and concluded that Smith experienced hallucinations and probably truly believed her bizarre writings to have come via a psychic connection with Mars.

At this point, there's no single clear way toward resolving the mysteries of the Voynich Manuscript. Rugg is developing his own rule-breaking codes (and he's offering a signed canvas to anyone who can crack them). Montemurro suspects that linguists and cryptographers will need to work together, not in isolation, to make any headway on Voynichese. Zandbergen thinks there might be clues in some of the weird flourishes in the book, like unique characters that appear only in the first line of paragraphs.

"What is absolutely certain," Zandbergen said, "is somebody made this. Somebody sat down and was writing it, with ink, on this parchment. It's real, so there must have been a method."

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.