Ancient Teeth Push Back Early Arrival of Humans in Southeast Asia

New tests on two ancient teeth found in a cave in Indonesia more than 120 years ago have established that early modern humans arrived in Southeast Asia at least 20,000 years earlier than scientists previously thought, according to a new study.

The new research consisted of a detailed reanalysis of the teeth, which were discovered in the Lida Ajer cave in western Sumatra by the Dutch paleoanthropologist Eugène Dubois in the 1880s. The researchers also revisited the remote cave to accurately date the rock deposits in which the teeth were found.

The findings push back the date of the earliest known modern human presence in tropical Southeast Asia to between 63,000 and 73,000 years ago. The new study also suggests that early modern humans could have made the crossing to Australia much earlier than the commonly accepted time frame of 60,000 to 65,000 years ago. [See More Photos of the Ancient Teeth Found in Indonesia]

The findings also provide the earliest evidence for the survival of early modern humans in a rainforest environment, according to the researchers.

Geochronologist Kira Westaway of Macquarie University in Sydney said that, until this recent study, the earliest evidence for modern humans in Southeast Asia came from the Niah caves in Malaysian Borneo, dated to around 45,000 years ago, and the Tam Pa Ling cave in northern Laos, dated to between 46,000 and 48,000 years ago.

Westaway is the lead author of the new study, published online Aug. 9 in the journal Nature, which includes contributions from 22 other scientists from Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States, the Netherlands, Germany and Indonesia.

Cave of secrets

Westaway said the remote Lida Ajer cave has been visited by scientists only a handful of times since Dubois discovered it in the 1880s.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The Lida Ajer cave has been shrouded in doubt ever since it was first found by Dubois," she told Live Science. "I love the fact that we've been able to come in and apply these modern techniques, which Dubois wouldn't have had access to."

Dubois became famous several years earlier, when his excavations on the Indonesian island of Java revealed the celebrated remains of "Java Man," a pre-modern human species now known as Homo erectus, estimated to be around 1 million years old.

Westaway made her own visit to the region in 2008, and spent more than a week exploring different limestone caves in the heavily forested highlands of western Sumatra before finding the cave described by Dubois in his field notebooks.

"The minute I walked in through the front entrance, I saw there was a calcite column at the back of the cave — a stalagmite and a stalactite that have joined together — which was described in his notebook, and I knew I was in the right spot," she said.

Two researchers also visited the Lida Ajer cave in September 2015 for the new study, to establish a firm chronology for the deposits where Dubois found the teeth.

"We didn't excavate so much, but rather we worked on documenting the cave — what it looks like, location of the fossil breccias, [and] collected samples for dating," Gilbert Price, a paleontologist at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, told Live Science in an email.

"We were able to tie Dubois' brilliant and important fossil collection back to the actual place that they came from," he wrote. "Having that provenance is very important."

Ancient teeth

Back in Australia, the samples from the cave were subjected to a barrage of dating techniques, which indicated that the sedimentary rock deposits and the fossils they contained were laid down between 63,000 and 73,000 years ago.

"Dating is notoriously difficult even at the best of times, and not every sample that we analyzed from Lida Ajer proved to be suitable," Price said. "We were very lucky to even get the results that we did.”

Price and his colleague Julien Louys, a paleontologist at the Australian National University in Canberra, visited the Naturalis Museum at Leiden in the Netherlands, which keeps an extensive collection of fossil remains from the Dubois excavations in Indonesia, including the two ancient teeth found at Lida Ajer.

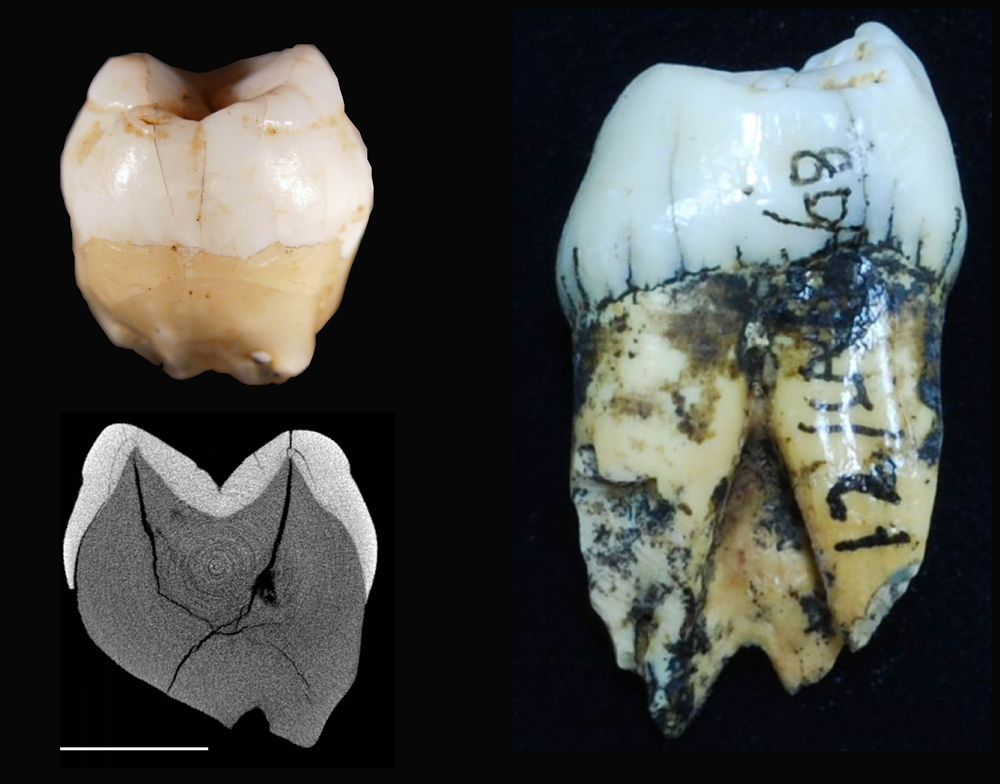

The two ancient teeth were put through a suite of analytical tests, including scanning techniques that allowed the researchers to examine the junction between the hard enamel coating and the softer dentin material inside, which is crucial for distinguishing human teeth from those of other primates.

"We realized that we had to reconfirm that these were anatomically modern human teeth by using these scanning techniques," Westaway said. "Otherwise, even if we came out with a new chronology, people would always be questioning if they were really human."

Out of Africa

The new study has established that anatomically modern humans have been widely dispersed throughout Southeast Asia for at least 63,000 years — and not just along the coasts, which is where human dispersal was mainly thought to have occurred.

"We always thought they would favor coastal sites as they were dispersing, because at the coast, there are a lot of resources, and it’s very easy to get around," Westaway said. "But not only have we not found them at the coast, we've found them a long way inland, and up in the highlands in a closed rainforest.”

Price explained that rainforests would have been a difficult environment for early modern humans to survive in, compared to coastlines.

"That's especially true considering that the ancestors of the Lida Ajer people were savannah-adapted, so had evolved in a very different environment," Price wrote. "Yet they were able to carve out a living in the rainforests of Sumatra back around 70-odd thousand years ago."

The findings also have implications for what is known about the dispersal of modern humans out of their original homelands in Africa to Asia, and eventually to Australia, Westaway said.

"The fact that it was found in western Sumatra, which is definitely not on the route that we would expect for modern human dispersal through that region, just goes to show that the dispersal was much more widespread than we acknowledge," she said.

Original article on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.