Belly Up: Why Ankylosaurs Are Always Found Upside Down

Like any homicide detective, dinosaur hunters search for clues hinting at how these ancient beasts died. One of these clues morphed into a mystery that researchers have just solved: Why is the armored, tank-like ankylosaurus almost always found on its back?

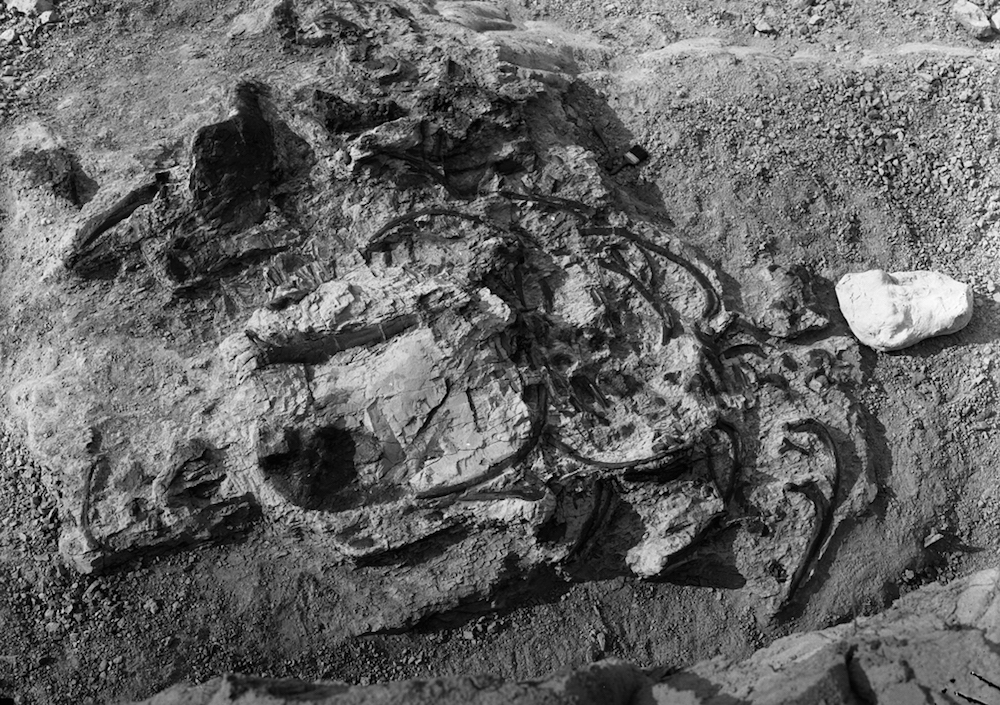

Paleontologists have puzzled over this belly-up death pose since 1933, and a new analysis shows that these observances weren't just coincidence: Out of 37 fossil ankylosaurs discovered in Alberta, Canada, 26 (70 percent) were found upside down, the researchers of a new study found.

The answer to this mystery was surprisingly straightforward, although it involved a touch of physics. These Late Cretaceous armored beasts were swept out to sea after they died, where they flipped over, sunk down to the seabed and fossilized, the researchers found. [Photos: See the Armored Dinosaur Named for Zuul from 'Ghostbusters']

Predators and roadkill

Before the researchers reached this conclusion, they overturned other hypotheses about the ankylosaurs' strange, upside-down position. One idea suggested that ravenous, dinosaur-age predators had turned over the ankylosaurs' dead bodies. But only one of the upside-down ankylosaurus had tooth marks on it, indicating that this wasn't the answer.

Another idea floated by dinosaur researchers alleged that after the dinosaurs died on dry land, their bodies filled with gas as they decomposed. This bloating might have caused them to roll over on their backs.

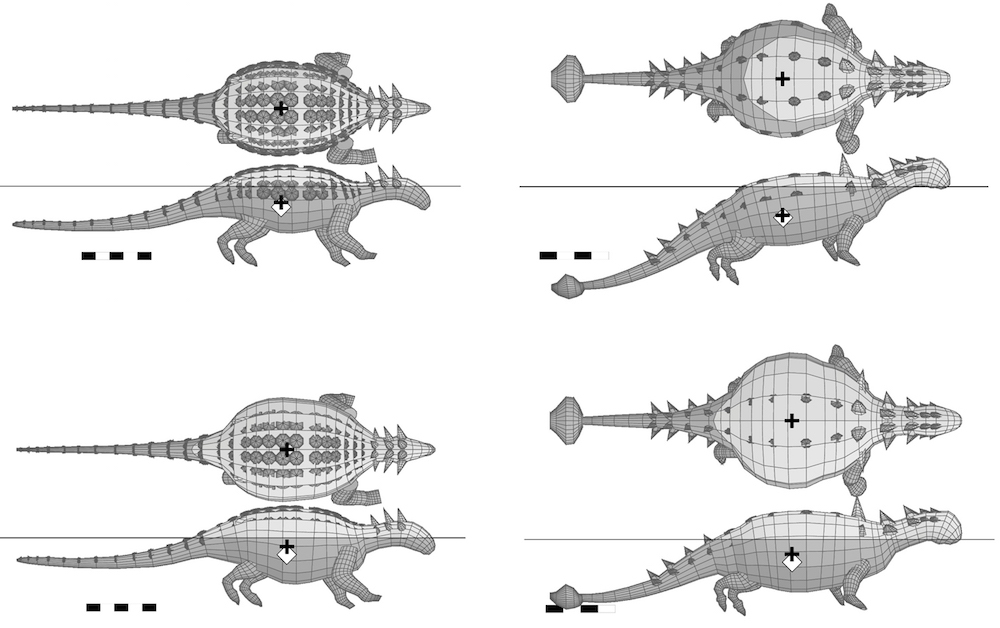

But this wasn't the answer either, the researchers found. There isn't any animal alive today that looks like the ankylosaur, a beast that could reach up to 26 feet (8 meters) in length, weighed up to 8 tons and had a long tail, sometimes with a bony club at the end. So, the researchers opted to observe armadillos, which also have tails and armored backs, and they walk on four legs.

To be specific, the researchers looked at 174 pictures of armadillo roadkill. But these dead animals were just as likely to be on their sides and bellies as their backs, even after the researchers accounted for bloating, abdominal rupture and scavenging.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It's almost split evenly, the three ways," said study co-researcher Donald Henderson, the curator of dinosaurs at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology in Alberta. "There's no preferred way of being dead."

Finally, the researchers tested what turned out to be the correct hypothesis — that the ankylosaurs had either drowned or been swept out to sea once they died.

"We used computer modeling to show that ankylosaurs likely flipped over due to a phenomenon called 'bloat-and-float,' where the gases that accumulate in the bloating belly of the carcass cause the animal to flip over while suspended in water," lead study researcher Jordan Mallon, a paleobiologist at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ontario, Canada, told Live Science in an email.

Mallon noted that most of the dinosaur skeletons found in Alberta are uncovered in river deposits, "but it seems, so far, that only the ankylosaurs are habitually found on their backs," he said.

Given that other dead dinosaurs didn't flip over in the water, how did the ankylosaur pull off this feat? The computer model showed that when an ankylosaur's center of gravity (a downward force) didn't match its center of buoyancy (an upward force), a disturbance such as a breeze, current or wave could cause the rotund, bloated animal to turn upside down, Henderson told Live Science. [Wipe Out: History's Most Mysterious Extinctions]

The finding may also apply to glyptodonts, animals that look like giant armadillos that went extinct about 10,000 years ago at the end of the last ice age, Mallon said.

"It's been said that glyptodonts, too, are often found on their backs, and we suspect that this may be due to a similar boat-and-float phenomenon," Mallon said.

The research has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, but "we think we've got a watertight case," Henderson joked. That case was presented Aug. 25 at the 2017 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting in Calgary, Alberta.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.