Super-Sticky Robot Clings Underwater Like 'Hitchhiker' Fish

A robot inspired by a hitchhiking fish can cling to surfaces underwater with a force 340 times its own weight.

The new bot was inspired by the remora, fish that cling to larger marine animals like sharks and whales, feeding off their hosts' dead skin and feces.

Remora fish do this with a specially adapted fin on their undersides called a suction disc, which consists of a soft, circular "lip" and linear rows of tissue called lamellae. The lamellae sport tiny, needle-like spinules. The remora can use tiny muscles around the disc to change its shape to suction itself to the host; the spinules then provide major gripping power by adding friction to the equation.

"Biologists say that it represents one of the most extraordinary adaptions within the vertebrates," said Li Wen, a robotics and biomechanics researcher at Beihang University in China and the lead author of a new paper describing the remora robot. [7 Clever Technologies Inspired by Nature]

Fishy inspiration

Wen said he got the idea for a remora-inspired robot when he was a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard University. He and his advisor were working on designing 3D-printed sharkskin. When looking up photos to use in a paper, Wen said, he kept seeing these odd little hangers-on in photos of sharks. They were remoras. Struck by the fact that no one had tried to make a biorobotic remora disc, Wen and his colleagues decided to tackle the project themselves.

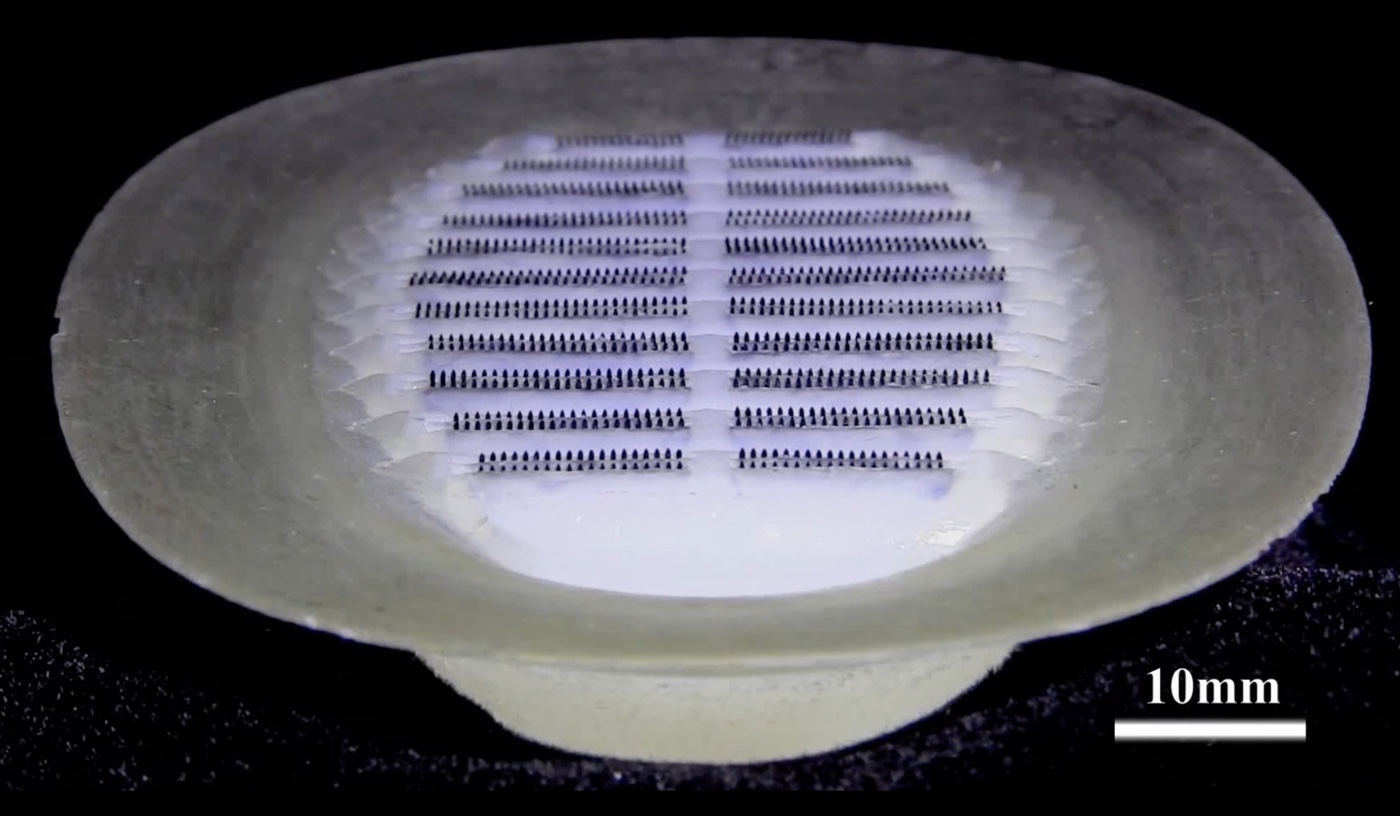

To do so, they had to come up with a way to create a disc with sections ranging from downright rigid to skin-soft. The researchers used 3D printing to pull off this feat, and then added approximately 1,000 faux spinules made of laser-cut carbon fiber. To allow the disc to move just like a real remora disc, the researchers embedded six pneumatic actuators — basically little air pockets — that could inflate and deflate on cue.

The result looks a bit like one of those shaving razors with far too many blades, just larger. The robot measures about 5 inches (13 centimeters) from end to end.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ride-along robot

To test this fishy bot, the researchers attached it underwater to a variety of surfaces, some rough, some smooth, some rigid and some flexible. These included real mako shark skin, plexiglass, epoxy resin and silicone elastomer. The robot clung quite nicely to all the surfaces, the researchers found.

The force needed to pull the remora robot off the smooth plexiglass was about 436 newtons, which translates to 340 times the weight of the robot itself. On rougher surfaces, the bot clung a little less tightly. It took about 167 newtons of force to pull the bot off real sharkskin, for instance.

Finally, the researchers attached their disc to a real remotely operated underwater vehicle and practiced attaching the ROV by the disc, to various surfaces. They had a 100 percent success rate attaching the disc to the same range of surfaces that they'd tested before, with an average time to attach of less than 4 seconds, the study said.

"The rigid spinules and soft material overlaying the lamellae engage with the surface when rotated, just like discs of live remora," Wen told Live Science.

While adhesive robots are nothing new, the remora is one of the first options roboticists have had for underwater attachments. Other sticky bots, like ones inspired by tree frogs and geckos, don't work well when submerged. The remora bot could be used to attach things to any broad underwater surface, Wen said, or to allow an underwater robot to cruise along on the underside of a boat.

Remora robots could even be used as tags for tracking the movements of marine animals, he said. After all, what's one more hitchhiker?

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.