Ancient Marsupial Relative Was Tree-Climbing Oddball

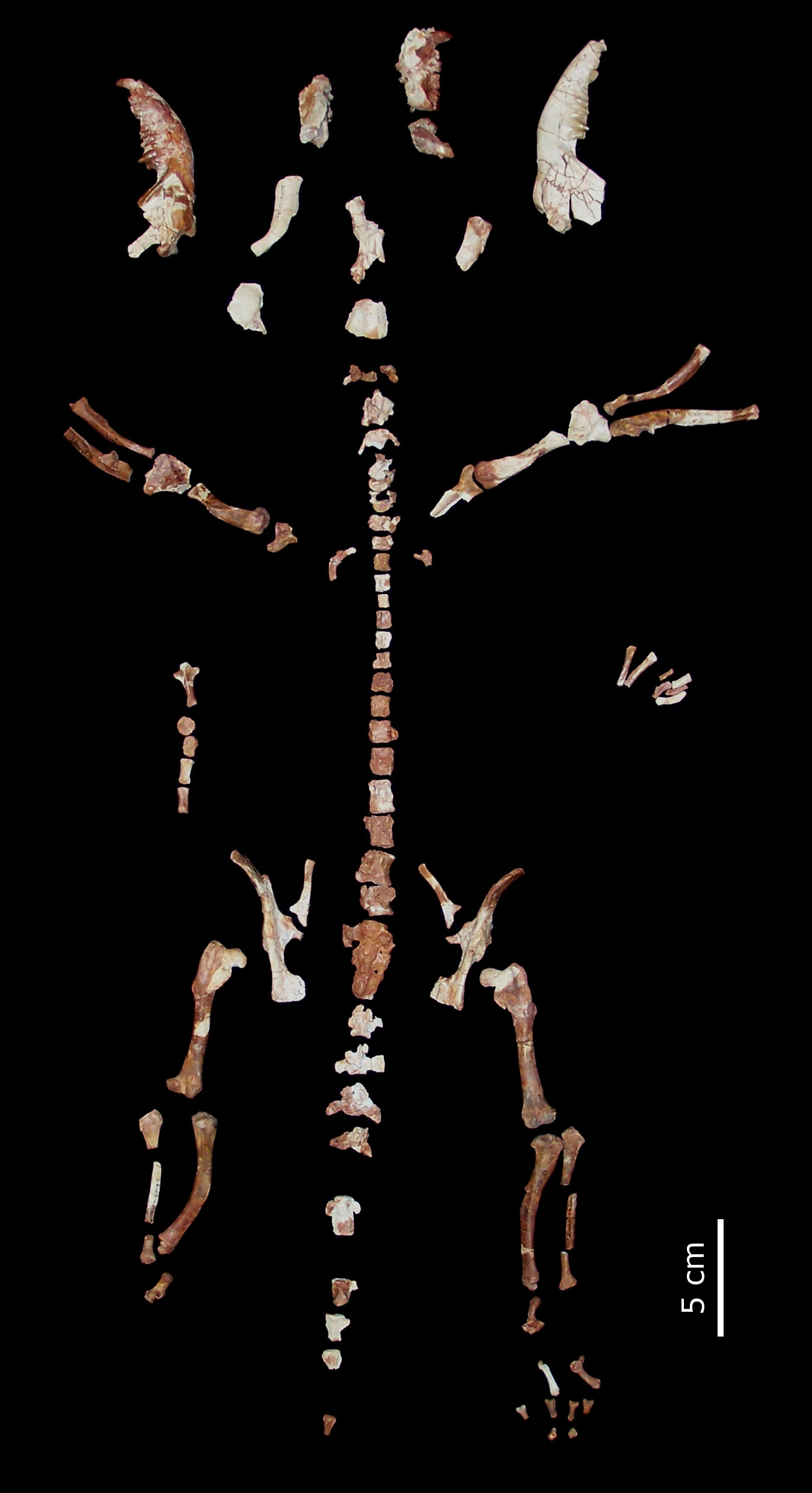

More than 40 million years ago, on a small island that has since coalesced with other islands to become modern-day Turkey, an odd beast the size of a domestic cat lived in the trees: a bone-crushing marsupial relative. Now, in a new study, researchers have described the near-complete skeleton of this ancient creature.

The remains of the marsupial relative, called Anatoliadelphys maasae, were found in the Turkish Uzunçarşıdere Formation, according to the scientists.

While today the most beloved and, arguably, most thrilling marsupials such as kangaroos and wallabies live in Australia, this isn't the only place they're found now — a slew of mouse-size opossums currently populate the Americas. Some insect-eating marsupials the size of mice or rats were also around in the Northern Hemisphere — North America and Europe — during the middle Eocene period, 43 million to 44 million years ago. [10 Extinct Giants That Once Roamed North America]

Still, Murat Maga, a coauthor of the recent study and assistant professor of pediatric medicine at the University of Washington, was surprised to have found a marsupial relative in that spot at all, he told Live Science. For Robin Beck,study coauthor and a lecturer in biology at the University of Salford, in the United Kingdom, the size of this creature was one of the big shocks.

"Here you have, at this site in Turkey, an animal that's much bigger — it's about 10 times bigger than the biggest marsupial relative from Europe or North America at about this time," Beck told Live Science. "And it has these big, big jaws [with] big crushing teeth ... The teeth are very worn, as well, so it was obviously crunching away at something pretty hard."

Marsupials — and their closely related marsupial relatives — are thought to have trouble competing against placental carnivores. But, the researchers think that this tree-climbing oddball, which may have been a bone-eating scavenger or a carnivore that fed on hard-shelled invertebrates such as snails (or both), didn't actually have to outcompete them.

It may simply be that this island didn't have any placental carnivores, they said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As far as Beck and Maga know, no placental carnivores have yet been discovered on the island that Anatoliadelphys maasae inhabited. And so, this creature may have been able to fill the ecological niche on the island for a predator, according to Chris Beard, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Kansas, who was not involved in this research.

This may also explain why the marsupial relative is no longer alive. Once Turkey came together 25 million years ago to form a land bridge, Anatoliadelphys maasae would have been subject to predation by the placental carnivores from Asia and the Middle East.

Consider this thought experiment, proposed by Beard: What would happen to lemurs, primates that live only on the island of Madagascar and nearby islands, if Madagascar became attached to continental Africa? Would lemurs continue to survive in a new world pulsing with leopards, baboons and pythons?

"If I would make a prediction, I would predict that they would probably all go extinct just because they can't compete with the African mammals, which have been evolving on a much larger landmass," Beard told Live Science.

The study was published Aug. 16 in the journal PLOS ONE.

Original article on Live Science.