A lost city that was overrun by Alexander the Great on his conquest of Persia has finally been unearthed in the Kurdish region of Iraq, decades after it was first seen on spy satellite imagery.

The site, called Qalatga Darband, was directly on the route that Alexander the Great took as he pursued the Persian ruler Darius III in 331 B.C. before their epic battle at Gaugamela. The site bears signs of Greco-Roman influence, including wine presses and smashed statues that may have once depicted the gods Persephone and Adonis.

"It's early days, but we think it would have been a bustling city on a road from Iraq to Iran. You can imagine people supplying wine to soldiers passing through," lead archaeologist John MacGinnis, from the British Museum, told The Times. [The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

Surprising spy data

In the 1960s, American spy satellite imagery, from the Corona satellite program, revealed the existence of an ancient site, near the rocky Darband-i Rania pass in the Zagros Mountains in Iraq. But that data was classified. When it was finally made public, archaeologists from the British Museum pored over the data. Later drone footage of the area revealed several large limestone blocks, as well as hints of larger buildings lying buried beneath the ground. However, by the time the archaeologists knew of the site's existence, political instability made it difficult to explore the region, they said.

Only in recent years has the area become safe enough for archaeologists from the British Museum to take a closer look. When they did, they found a huge trove of ancient artifacts. The ceramics found at the site suggest that at least one area of Qalatga Darband was founded during the second and first centuries B.C. by the Seleucids, or the Hellenistic people who ruled after Alexander the Great, according to a statement. Later, the Seleucids were overthrown and followed by the Parthians, who may have built extra fortification walls to protect against the Romans who were encroaching during that period.

The site contains a large fort, as well as several structures that are likely wine presses. In addition, two buildings employ terra-cotta roof tiles, which are characteristic of Greco-Roman architecture of the time, the researchers noted in a statement.

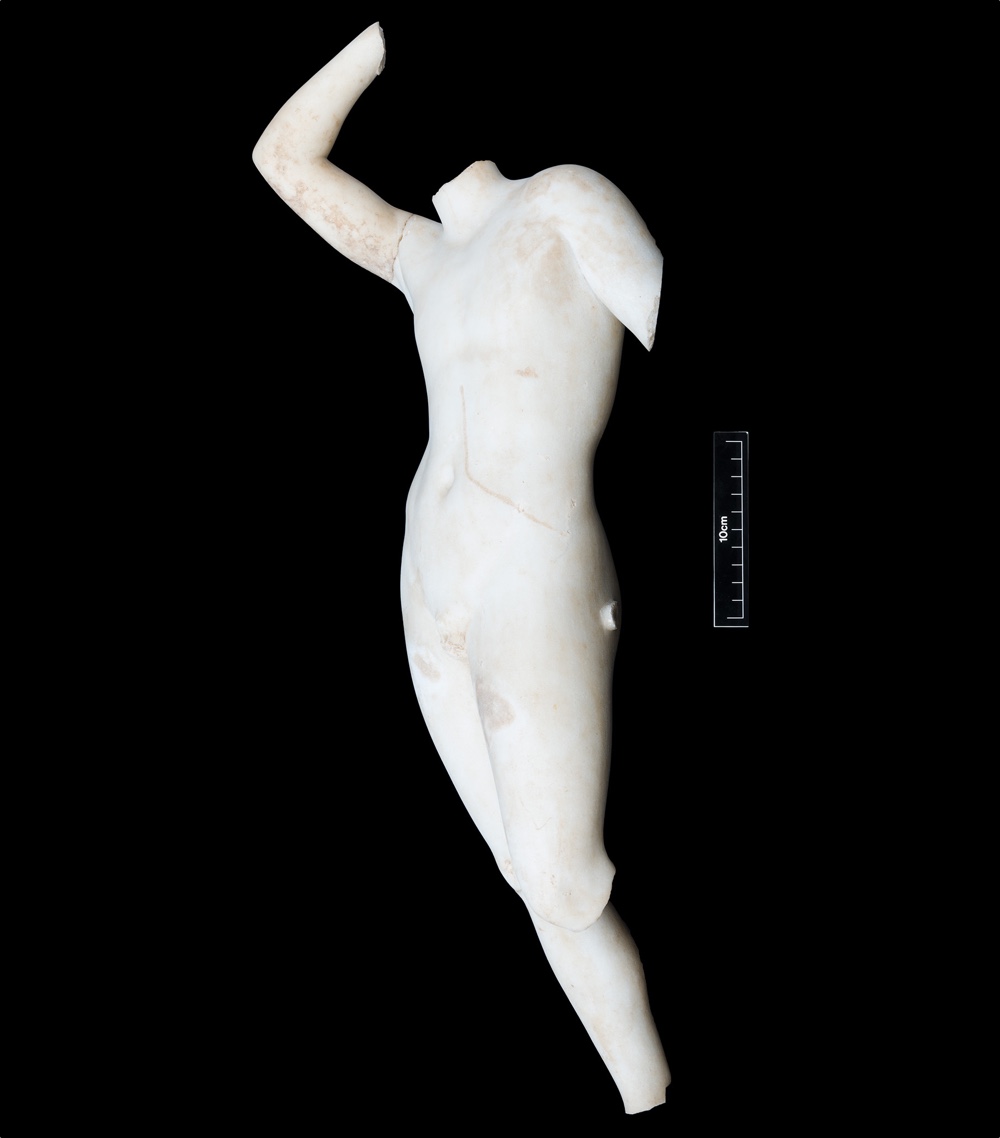

On the southern end of the site, archaeologists found a large stone mound, beneath which was a giant temple-like structure. The building contained smashed statues that looked like Greek gods. One, of a naked man, was likely to be Adonis, while another seated female figure was probably the goddess Persephone, the reluctant bride of Hades, ruler of the underworld, according to the statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Nearby in the Darband-I Rania mountain pass, archaeologists have also uncovered evidence of an even older settlement. That fortress likely dates to the Assyrian period, between the eighth and seventh centuries B.C. The fort had 20-foot-thick (6 meters) walls and was likely a way for the Assyrians to control the flow of people through the pass. At the same site, archaeologists uncovered a grave with a coin that dates to the Parthian period, the researchers said.

The grave bore the inscription "King of kings, beneficent, the just, the manifest, friend of the Greeks, this is the king who fought against the Roman army led by Crassus at Carrhae in 54/53 BC."

That inscription suggests the grave belongs to King Orodes II of Parthia, who ruled between 57 B.C. and 38 B.C., and may have referred to a period when the Romans attempted to conquer the Parthian Empire. The Parthians deflected that attack with horse-riding archers who shot arrows down on the Roman troops, according to the statement.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.