Antarctic Iceberg's Split Reveals Ecosystem Hidden for Thousands of Years

A giant iceberg that broke away from an ice shelf in the Antarctic Peninsula in July is slowly revealing a vast undersea ecosystem that has been hidden for thousands of years, researchers say.

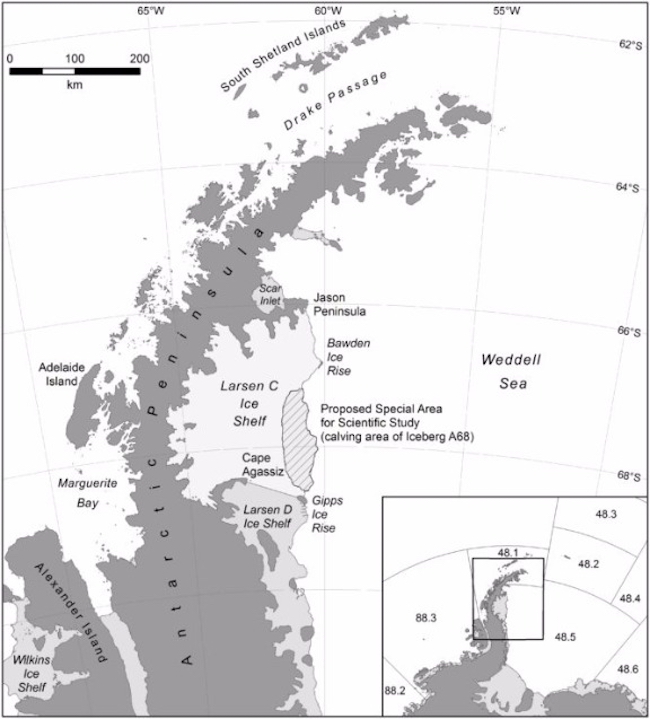

As the iceberg, known as A-68, moves away from the Larsen C ice shelf and into the Weddell Sea, it will eventually expose 2,240 square miles (5,800 square kilometers) of seafloor that has been buried under the ice for up to 120,000 years, without light and linked to the open ocean only by minimal currents, according to scientists with the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

Now, scientists are keen to begin exploring the newly exposed area as soon as possible, to conduct research on the hidden ecosystem that can be used to make comparisons with any changes that occur over the years to come. [In Photos: Antarctica's Larsen C Ice Shelf Through Time]

"It's just a fantastic, unknown area for scientific research," said Susan Grant, a marine biologist with the BAS. "We know very little about what might or might not be living in these types of areas, and especially how they might change over time."

Grant is one of two BAS scientists who led a successful proposal for international protection of areas on the Antarctic Peninsula that are exposed when floating icebergs break away from the coast-bound ice shelves.

The Larsen C area will be the first to benefit from a 2016 agreement by the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), an international conservation agency, following the proposal by Grant and her colleague Phil Trathan, head of conservation ecology for the BAS.

The designation of the newly exposed region as a special area for scientific study will prohibit commercial activities like fishing and tourism for an initial period of two years, with an option to extend the protection for another 10 years after that, and potentially indefinitely, according to the BAS.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hidden seafloor

Studying the area exposed as the A-68 iceberg floats away from the coast will let scientists learn more about such events, which are expected to become more common, including how wildlife responds as the ecosystem changes, Grant said.

"There's this vast area which has been covered for thousands of years," Grant told Live Science. "We know the physical changes are likely to be huge when the ice moves away, and the ecosystem is likely to change along with that."

Grant added that there is no evidence that this event is a direct result of climate change, but "we do expect that these sorts of things may happen more frequently in the future, so understanding how things respond to this kind of change is really important"

Scientific knowledge of the ecosystems below Antarctic ice shelves is mainly limited to the results of two German expeditions to the Larsen A and Larsen B areas, located north of Larsen C on the Antarctic Peninsula, where sections of the ice shelf broke away in 1995 and 2002, Trathan said.

"It took 5 years and 12 years for scientists to actually get into Larsen A and B, and by that time, there was already a lot of colonization [by new species] going on," Trathan told Live Science.

The regions covered by ice shelves were entirely without sunlight, and there was no "marine snow" of dead phytoplankton and feces of zooplankton and fish — a crucial food resource in other parts of the ocean, Trathan said. [Antarctica Photos: Meltwater Lake Hidden Beneath the Ice]

"Life there is sparse," he said. "The working hypothesis is that it is similar to the very deep oceans, but that is something that needs to be tested."

Scientists suspect there are rapid changes to the ecosystems of the seafloor and the water above in newly exposed areas, Trathan said.

"You'll have sunlight, you'll have phytoplankton, and you'll begin to get zooplankton and fish in there pretty quickly. You'll probably also get seabirds and marine mammals are going to begin to forage in that area," he said. "So, it will be sort of a chain reaction — as you get productivity happening then you'll get more species coming in, and so there will be quite significant changes over relatively short time scales."

Ecological change

One of the first challenges for scientists will be to find the funding and resources needed for expeditions into the area, hopefully before any significant changes have taken hold in the hidden ecosystem, mainly as a result of exposure to sunlight and ocean currents, Grant said.

According to the new study, published online Sept. 28 in the journal Nature, a South Korean expedition could be diverted to the area in early 2018, and a German expedition will conduct a biodiversity survey there in 2019. The BAS is also considering sending a research vessel in early 2018.

"It's very difficult to mobilize research efforts — it takes a lot of money, and ship time is not an easy thing to arrange, especially at short notice," Grant said. "But the fact that a lot of groups are trying really hard to get something down there demonstrates that this is a really unique opportunity."

Julian Gutt, a marine biologist with Germany's Alfred Wegener Institute, led two scientific expeditions to the Larsen A and B ice shelves in 2007 and 2012, a few years after parts of both ice shelves had broken away and exposed large areas of the seafloor.

At that time, the exposed seafloor areas were still mainly populated by deep-sea animals: "sea cucumbers, brittle stars, sea stars, deep sea sponges, things like that," Gutt told Live Science.

Similar deep-sea species were also found on continental shelf regions in Antarctica and the Arctic, he said, but the abundance of such species was much higher under the ice shelves, especially under Larsen B.

One of the earliest changes was the development of phytoplankton blooms in the open water when such areas were exposed to sunlight, which led in turn to the development of populations of zooplankton and small crustaceans known as krill, he said.

Minke whales, a krill-feeding species, were the first marine mammals seen to take advantage of the new food resources in the exposed areas, while also evading orcas, their most common predator. Orcas are found in higher latitudes and seemed slower to adapt to a more southern habitat, Gutt said.

The newly exposed areas may follow a similar pattern of colonization by wildlife species as Larsen A and B, but Larsen C might also prove to be entirely different, Gutt said.

"This is quite an interesting challenge in this kind of marine ecology — how an ecosystem develops can be very important, and the results will [let scientists] assess how fast they can respond to any environmental changes, including climate change and anthropogenic changes," he said. "So, this can be seen as a big experiment carried out by nature, and we can learn from this big experiment how marine systems develop under the pressure of environmental change."

Original article on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.