Hidden Upside-Down Canyon Revealed on Underside of Antarctic Ice

A mysterious world of upside-down canyons crisscrosses the underbelly of Antarctica's ice shelves.

Now, research finds that some of these crevasses may contribute to both the thinning of the shelves and sea-level rise. A single canyon in the Dotson ice shelf in West Antarctica is responsible for dumping 4.4 billion short tons (4 billion metric tons) of freshwater into the Southern Ocean, according to Noel Gourmelen, a remote-sensing researcher at The University of Edinburgh. [50 Amazing Facts About Antarctica]

Icy divots

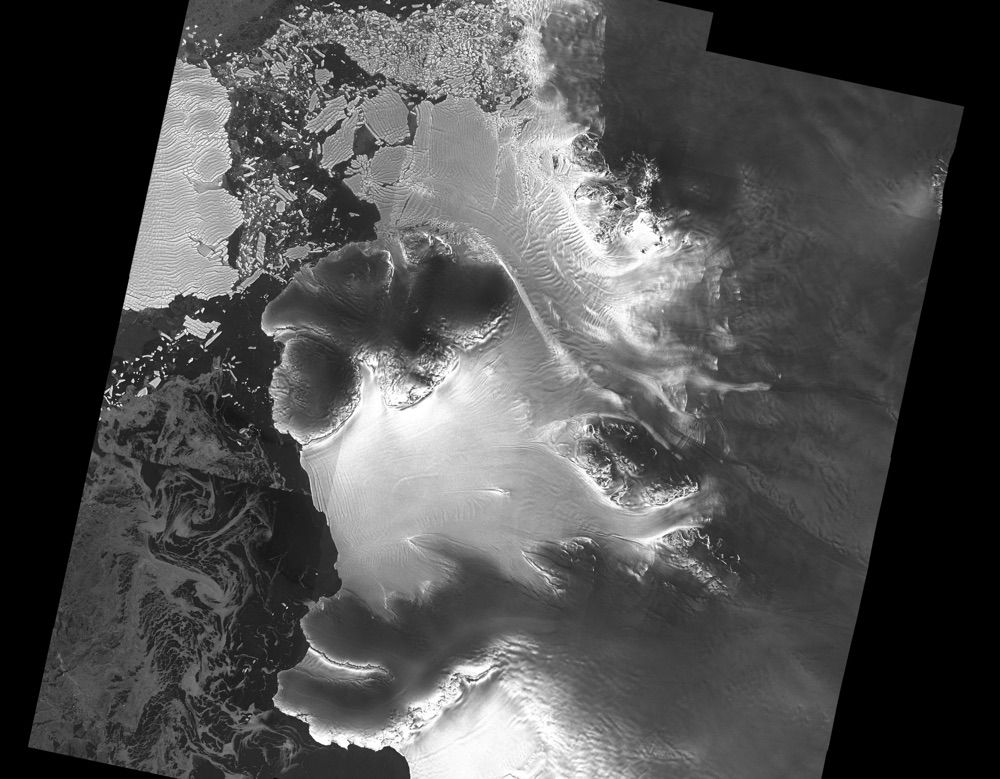

These divots in the underside of the ice shelves are poorly understood, according to the European Space Agency (ESA). To learn more, Gourmelen and his colleagues have been using data from ESA's CryoSat and Copernicus Sentinel-1 satellites to peer into the invisible under-ice world of the Antarctic canyons.

Both of these satellites use radar techniques to gauge ice-shelf thickness and dynamics. The team used the data to investigate the flow of the Dotson ice shelf, a 30-mile-wide (50 kilometers) expanse off the remote coast of Marie Byrd Land.

"We have found subtle changes in both surface elevation data from CryoSat and ice velocity from Sentinel-1, which shows that melting is not uniform, but has centered on a 5-km-wide [3 miles] channel that runs 60 km [37 miles] along the underside of the shelf," Gourmelen said in a statement.

This under-ice canyon is probably formed by relatively warm ocean water — 33.8 degrees Fahrenheit, or 1 degree Celsius — that circulates clockwise and upward due to the planet's rotation, Gourmelen said.

"Revisiting older satellite data, we think that this melt pattern has been taking place for at least the entire 25 years that Earth observation satellites have been recording changes in Antarctica," he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In that time, he said, the warm water has created an upside-down canyon in the bottom of the ice shelf that is up to 124 miles (200 km) deep and 9 miles (15 km) wide. The crevasse is deepening by about 22 feet (7 meters) each year, Gourmelen said.

"The strength of an ice shelf depends on how thick it is. Since shelves are already suffering from thinning, these deepening canyons mean that fractures are likely to develop and the grounded ice upstream will flow faster than would be the case otherwise," he said, referring to the land-based ice that is buttressed by the floating ice shelves. This land-based ice has a greater impact on overall sea-level rise because it's not already floating in the ocean. (When floating ice melts, it doesn't directly impact sea levels.)

The next goal, Gourmelen said, is to expand the same line of research to the rest of the ice shelves ringing Antarctica.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.