The Best Science Books

Predictably Irrational (Dan Ariely)

In the book, Dan Ariely, who researches behavioral economics at Duke University, posits that while we all like to think of ourselves as rational, we are largely irrational. That said, we are irrational in similar and highly predictable ways. Ariely also delves into how social context alters decision-making. The vignette-like descriptions of each experiment make the book easy to devour, and a few will stick with you.

In one particular experiment, Ariely's team was exploring how people order food at a restaurants, when they are not the first person in their group to order. The researchers found that in countries that generally value individualism, like the United States, if the first person to place an order requested the meal the second person was considering, the second person would change their order to something different, and then report dissatisfaction later. By contrast, in countries that value fitting in, it was more common to have an entire table of people order whatever the first person had ordered, with mixed reactions after the fact. — Mona Bushnell, Live Science Contributor

Patient H.M. (Luke Dittrich)

Most people who have waded into the field of psychology or neuroscience have heard of Patient H.M., a man who, at the age of 27 in 1953, got a lobotomy and lost the ability to form new memories. The world learned H.M.'s true identify — Henry Molaison — when he died in 2008. But now, we're invited to dive into Molaison's life and the years of research spent on his brain thanks to Luke Dittrich, the grandson of the surgeon who performed the lobotomy. Dittrich masterfully weaves together the history of neurology with the events that brought Molaison to his grandfather's operating table. He teaches the reader about inaccuracies that plagued neurology for decades, and delves into problems encountered and perpetuated by the researchers who studied Molaison's abilities after his life-changing surgery.

The book is nonfiction, but it reads almost like a novel. Dittrich's writing is superb, as he explores the nuances and mysteries of human memory and the journeys taken by Molaison, the doctors who studied him and even of Dittrich's own family, which has a dark secret of its own about lobotomies. — Laura Geggel, Live Science Senior Writer

A Brief History of Time (Stephen Hawking)

Stephen Hawking explains the universe. In this best-seller, the renowned physicist breaks down black holes, space and time, the theory of general relativity, and much more, and makes it accessible to those of us who aren't rocket scientists. The book is a great primer for anyone who wants to learn more about the origins of the universe, and where it's all heading.

Alex & Me (Irene M. Pepperberg)

"Alex & Me" (Harper, 2008) pulls readers into the amazing world of animal intelligence. In fact, after reading about Alex, the African gray parrot who learns countless words, simple math and the nuances of spoken language, you'll never use the insult "bird brain" again.

The book starts with author Irene M. Pepperberg mourning the loss of Alex, who passed away at age 30 in 2007. The beginning is a bit morose, but don't let that stop you. After the first chapter, you'll literally fly through the book, learning about how Pepperberg trained Alex to become — very likely — the smartest parrot in the world.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

I still remember a scene that made me laugh out loud. Pepperberg wanted to show Alex's mathematical talents off to a colleague, but Alex kept on giving the wrong answer. Frustrated, she told Alex that he needed to go back to his cage. Suddenly, Alex blurted out the right number, and said, "I'm sorry!" a phrase that she had never taught him, but that he had picked up by listening to people in the lab. "Alex & Me" is a delightful read, and makes you stop to wonder at the intelligence of animals in our world. — Laura Geggel, Live Science Senior Writer

A Beautiful Mind (Sylvia Nasar)

Get inside John Nash's head in this biography that examines the famed mathematician's important contributions to game theory, as well as his struggles with paranoid schizophrenia. Sylvia Nasar's captivating book charts Nash's life, from his youth in West Virginia to his research at Princeton University. His research was hugely influential in economics led to a Nobel Prize. Nasar's book was also made into a movie by the same name, starring Russel Crowe and Jennifer Connelly as Nas's wife Alicia.

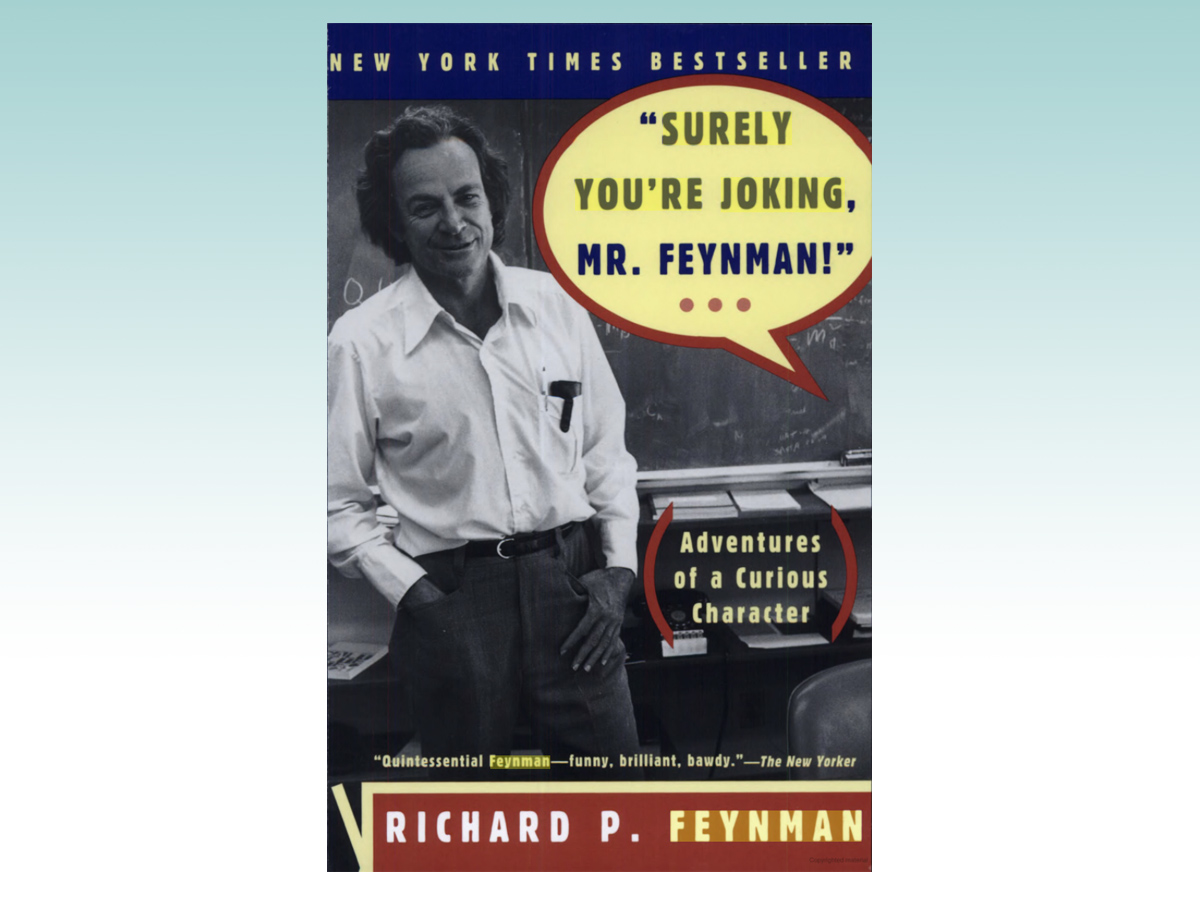

Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman! (Richard Feynman)

Arguably one of the most "curious characters," Richard Feynman was a physicist whose life was as eccentric as his experiments. In this book, Feynman dances from a childhood experience in which he had his parents, unknowingly, test a burglar alarm he'd concocted to his rap sessions with Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr in which the geniuses talked about atomic physics. The Nobel laureate describes his life's adventures, and sometimes unscrupulous behavior, while weaving in physics and the scientific method. In a review in the New York Times in 1985, when the book came out, K.C. Cole writes: "Many science buffs, I'll wager, are going to be unnerved by this book. After all, here is Richard Feynman — adjudged by most of his peers to be the world's best theoretical physicist - prancing around like a naughty schoolboy, sniffing his own footprints on all fours to see if he can follow his tracks as well as his dog can, being offered ''cream or lemon'' at a Princeton tea and blithely accepting both."

Is Feynman joking after all? You be the judge, but as Cole put it in the NYT article, "One of Mr. Feynman's favorite ploys is to fool people by telling the simple truth."

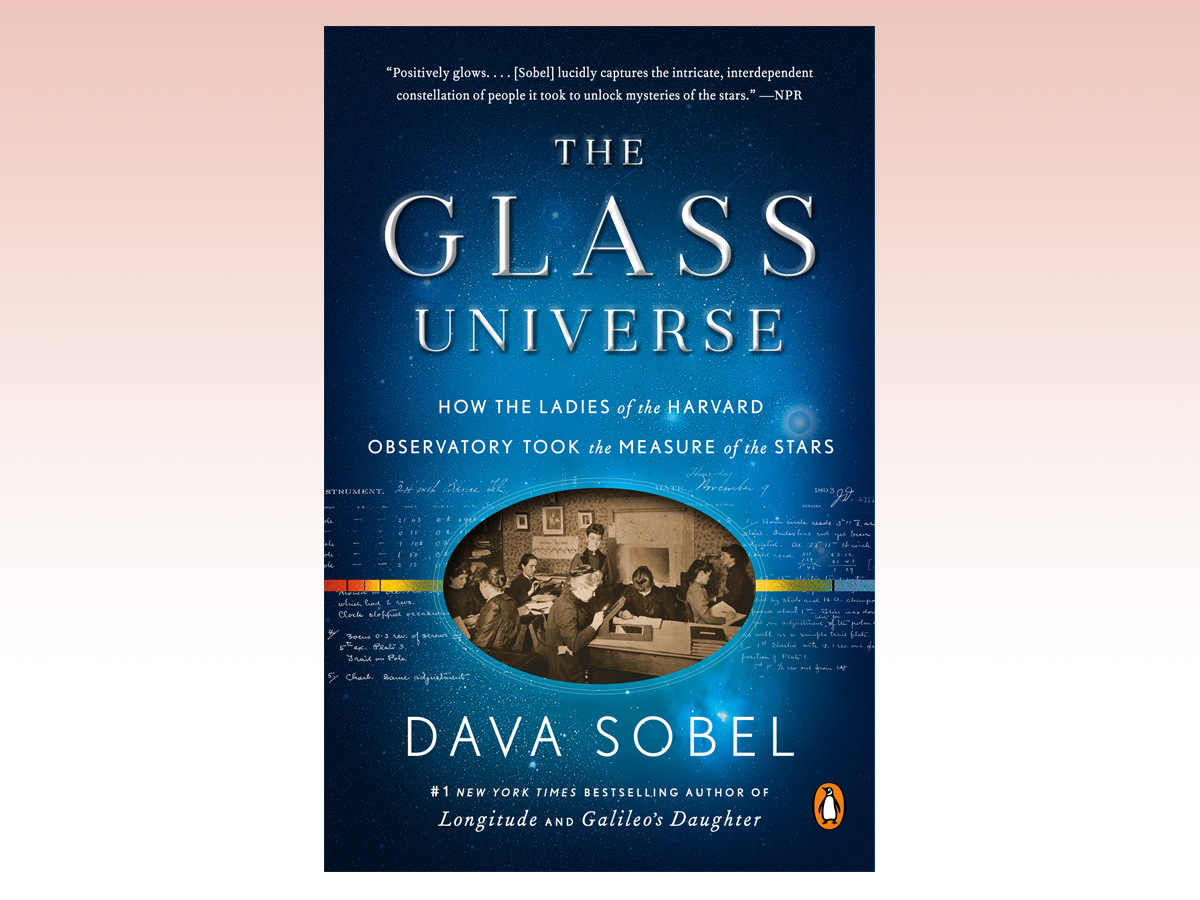

The Glass Universe (Dava Sobel)

Dava Sobel, a former science writer at the New York Times, delves into the lives and work of a group of women astronomers hired by Harvard University; women at the time, in the early 1900s, were not called astronomers and often referred to as "human computers," according to a review of the book by NPR. The scientists meticulously catalogued the stars of the universe by analyzing glass photographic plates holding light from the heavens. Writing in a review published online on the Guardian, Nicola Davis writes: "Sobel prevents the ceaseless grind behind the women’s success becoming burdensome for readers, peppering her history with intriguing details of the world in which they lived, from the 'fly spanker' — a tiny glass plate bearing stars of various brightnesses, for comparison – to the revelation that to keep astronomers supplied with milk, the Lowell Observatory in Arizona “had accommodated a dairy cow named Venus."