Shrews' Heads (and Brains) Shrink As Seasons Change

In creatures with backbones, skulls get progressively bigger as the animal grows to maturity, but then tend to stay the same size thereafter. However, something happens to the skulls of adult red-toothed shrews that is exceedingly rare among vertebrates: The animals' heads shrink and expand in synch with seasonal changes.

For the first time, a team of researchers has documented the complete cycle of these dramatic changes in living Sorex araneus shrews, describing their findings in a new study published online today (Oct. 23) in the journal Current Biology.

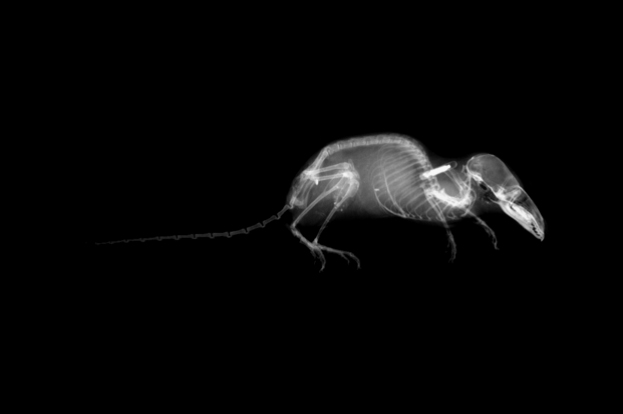

The researchers captured X-ray images that recorded the shrunken and recovered states of the shrews' skulls and brains, finding that the animals' heads contracted by up to 20 percent in preparation for winter and ballooned back to their previous size over the spring and summer. [The World's 6 Smallest Mammals]

This shift in skull size— known as the Dehnel effect — was previously documented in studies of the skulls removed from deceased shrews. But this is the first evidence to track this remarkable adaptation in living animals over time and link it to other biological changes, the study authors reported.

For the new investigation, scientists captured 12 wild red-toothed shrews, so named because of a reddish tint in their front teeth caused by iron deposits in the enamel, according to a study published in 2006 in the Journal of Mammalogy.

The researchers weighed the shrews and X-rayed their heads, measuring the length of the skulls and of the tooth rows, and the height and weight of the braincases. The scientists released the animals after implanting tiny devices that could transmit and receive radio signals, so the investigators could trap the same individuals repeatedly and compare measurements taken at different times.

As months went by, each of the shrews — males and females — showed significant changes in all of the recorded skull measurements, the study found. From September to February, as winter took hold, the animals' heads shrank by about 15 percent on average, while their body mass decreased by about 18 percent. Seasonal loss in body mass in shrews is partly due to shrinkage of the shrews' organs, particularly the liver and kidneys, according to a study published in 2000, in the journal Nature.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Then, beginning in February, the scientists observed that the process reversed. Over the next four months, the animals' then-reduced body masses increased by about 83 percent, while their braincases gained about 9 percent of their original size. And by the height of summer, the shrews had recovered nearly all the mass and length they had lost, the researchers wrote in the study.

Red-toothed shrews have a life span of around 18 months; they mate and die during their second summer of life, shortly after regaining their pre-winter mass and head size, the study authors reported.

The biological mechanisms driving these unusual changes in the shrews are still uncertain, but the phenomenon represents "an extraordinary adaptive process," according to the study. An average drop of about 19 percent in their body mass decreases the shrews' resting metabolic rate by approximately 18 percent, potentially reducing their food requirements and improving their chances of surviving winter conditions when food is scarce, the researchers explained.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.