Primordial Fossils of Earth's 1st Trees Reveal Their Bizarre Structure

Researchers made the discovery after studying the fossils of 374-million-year-old trees found in northwest China. The fossils showed that these ancient trees had an interconnected mesh of woody strands, the researchers found.

"It's just bizarre," said study co-researcher Christopher Berry, a senior lecturer of paleobotany at Cardiff University in the United Kingdom. [Nature's Giants: Photos of the Tallest Trees on Earth]

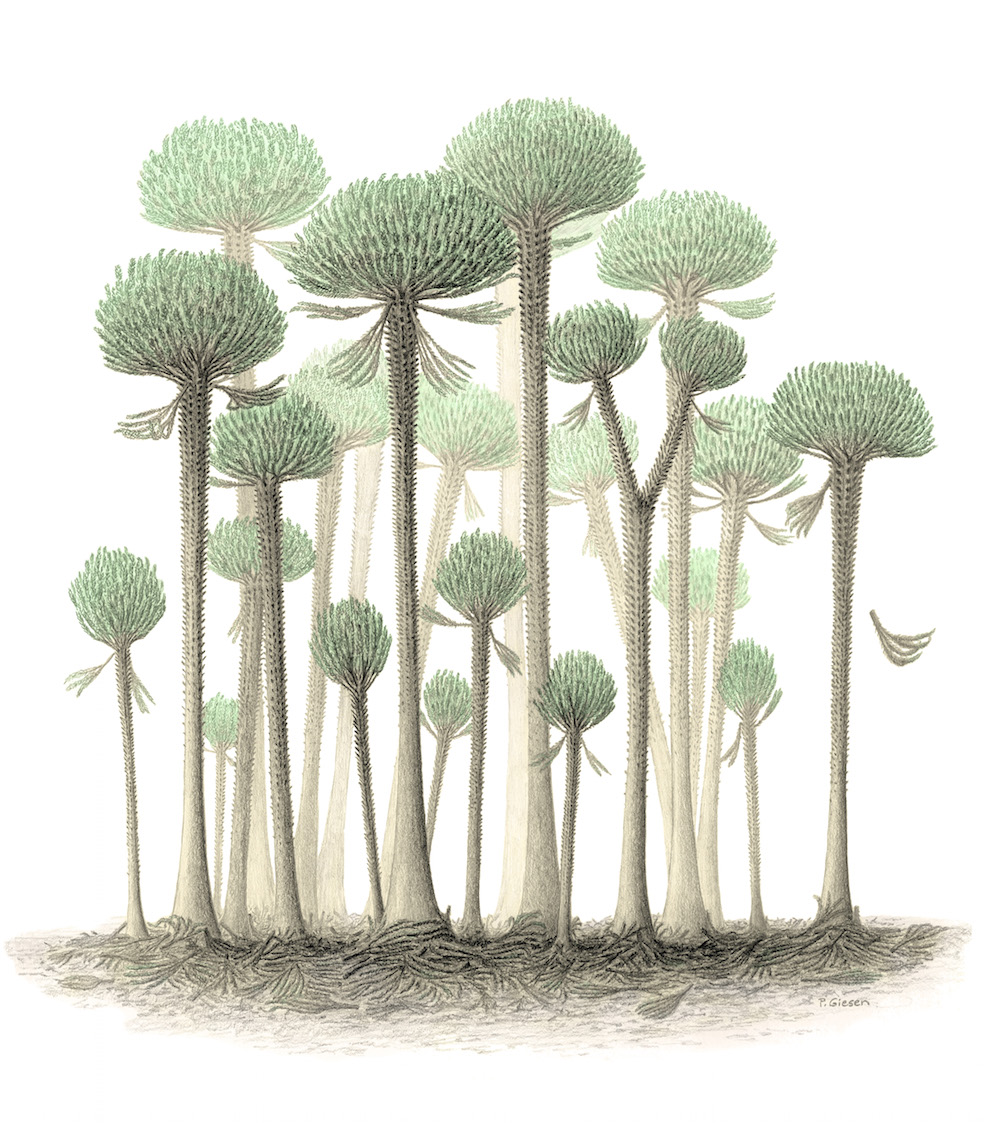

The two specimens were found in 2012 and 2015 in Xinjiang, China, by study lead researcher Hong-He Xu, of the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The specimens belong to a group of trees known as cladoxylopsids, which are known to have existed from the Middle Devonian to the Early Carboniferous periods, from about 393 million to 320 million years ago, long before dinosaurs walked the Earth.

Prior to these discoveries, researchers knew about fossilized cladoxylopsids from other locations, including Scotland, Germany and Gilboa, in upstate New York. However, these fossils didn't have the extreme detail needed to map the trees' anatomy. For instance, the 385-million-year-old Gilboa stumps were preserved in sand, which made it challenging to study their anatomy, Berry said.

"Most of it is just sand. It's very frustrating," Berry told Live Science. "We came up with different scenarios to try to figure out how this tree would grow, but we just couldn't figure it out."

A volcanic environment preserved the newfound specimens in much more detail than the cladoxylopsid specimens in New York, Berry said.

Trees within trees

The researchers named the newfound species Xinicaulis lignescens, which translates to "new stem becoming woody" ("Xin" means "new" in Mandarin; "caulis" means "stem" in Latin" and "lignescens" is Latin for "becoming woody.")

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

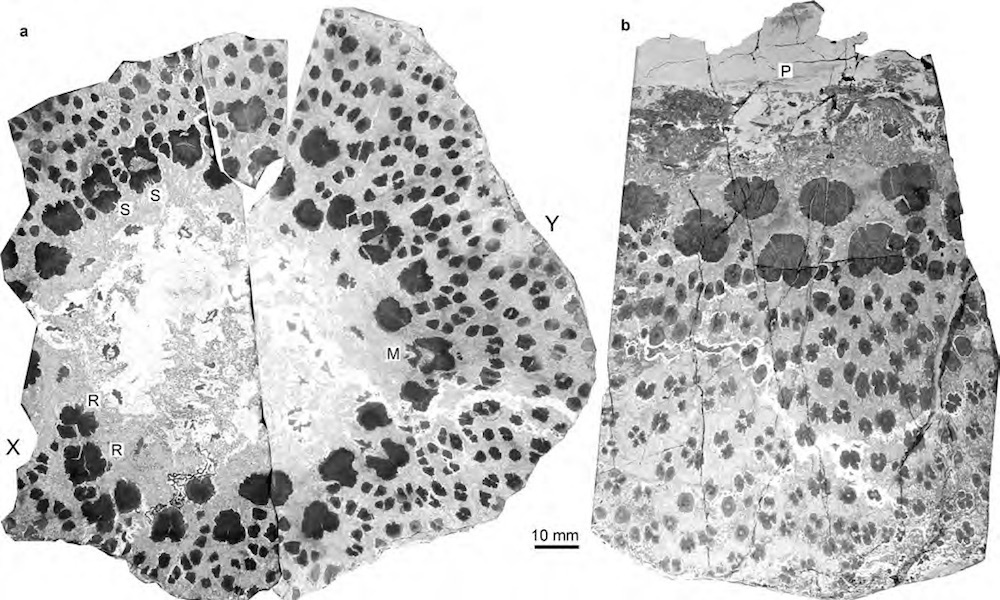

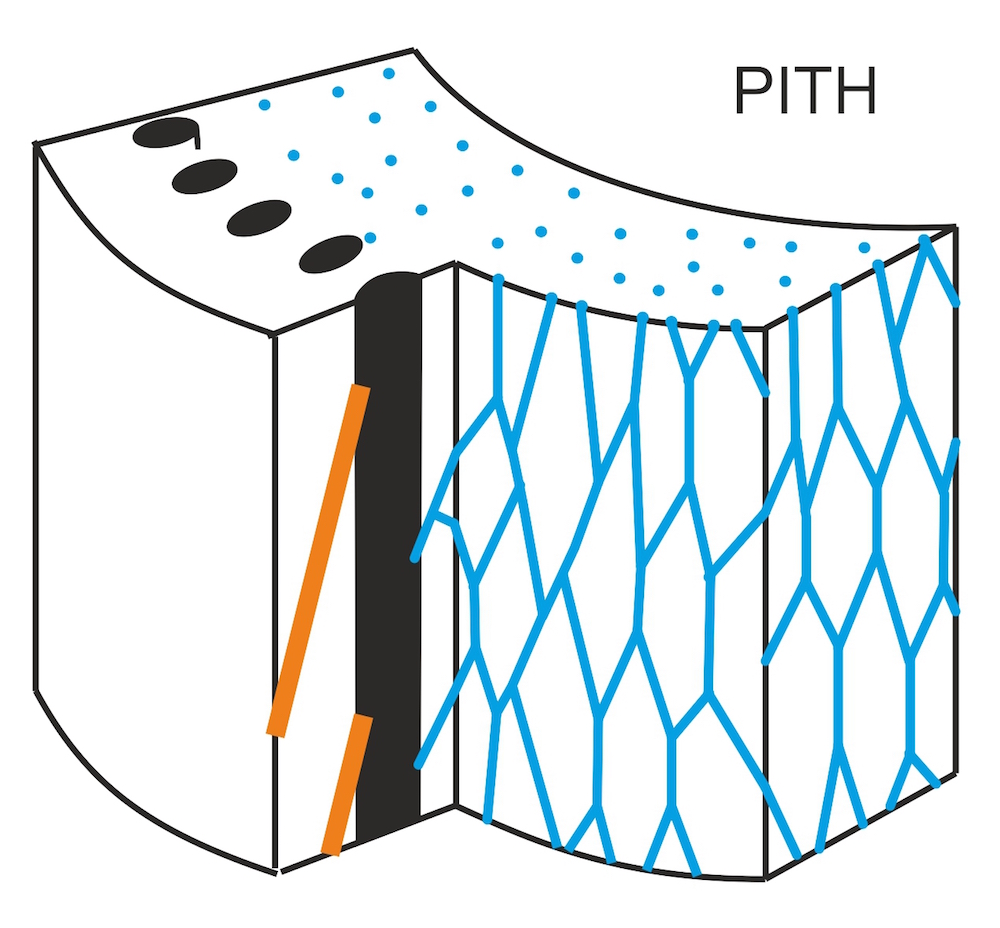

X. lignescens was filled with hundreds of xylems, woody tubes that carry water from the roots of the tree to its branches and leaves. In most modern trees, the xylem goes up the center of the tree, and a new growth ring is added each year around it. In other trees, such as palm trees, the xylem is found in strands that are embedded in spongy tissue throughout the trunk.

Unlike modern trees, the xylems of X. lignescens was arranged in strands on just the outer 2 inches (5 centimeters) of the tree, which meant the middle of the trunk was hollow, the researchers found. What's more, the xylem strands were connected to one another with a web of supportive strands, the researchers said.

Surprisingly, each xylem had its own set of growth rings. As these hundreds of rings and their supportive webs grew, the tree got fatter over time, the researchers found. Examining cross sections of X. lignescens was like looking at hundreds of tiny trees within a larger tree, Berry said.

As the xylems grew, they pulled at their supportive webs. This web would break but then repair itself, the researchers found by studying the volcanically preserved fossils.

"What you see, basically, is the way that each individual strand is growing, and the fact that it's slowly ripping itself apart but repairing itself at the same time," Berry said. "That's the key to how this thing grew. It's just incredibly complex." [Photos of First Fire-Scarred Petrified Wood]

Other cladoxylopsid fossils show that the tree had a pyramid-like base that tapered as it got taller. The new specimens reveal the mechanism behind this curious shape: As the tree's diameter grew, the xylems went from the side to the base of the tree, creating the well-known flat base and tapering trunk, the researchers said.

Berry said he plans to continue to study these trees, and determine how much carbon they could capture from the atmosphere, as well as how this impacted the climate.

The study was published online today (Oct. 23) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.