It's Official: Earliest Known Marine Astrolabe Found in Shipwreck

More than 500 years ago, a fierce storm sank a ship carrying the earliest known marine astrolabe — a device that helped sailors navigate at sea, new research finds.

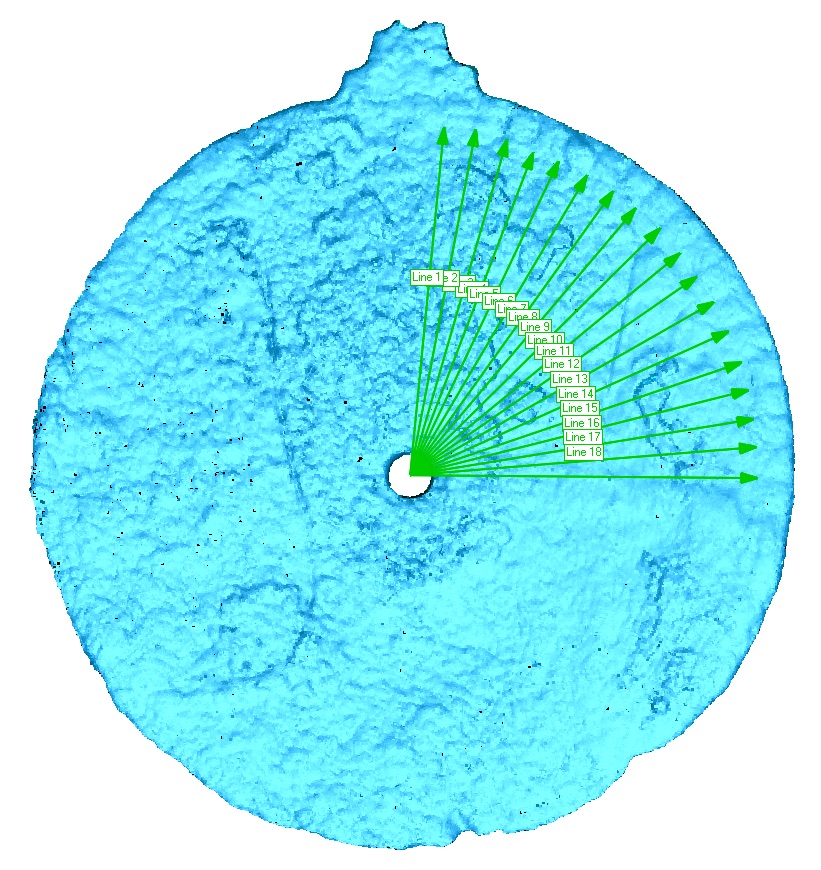

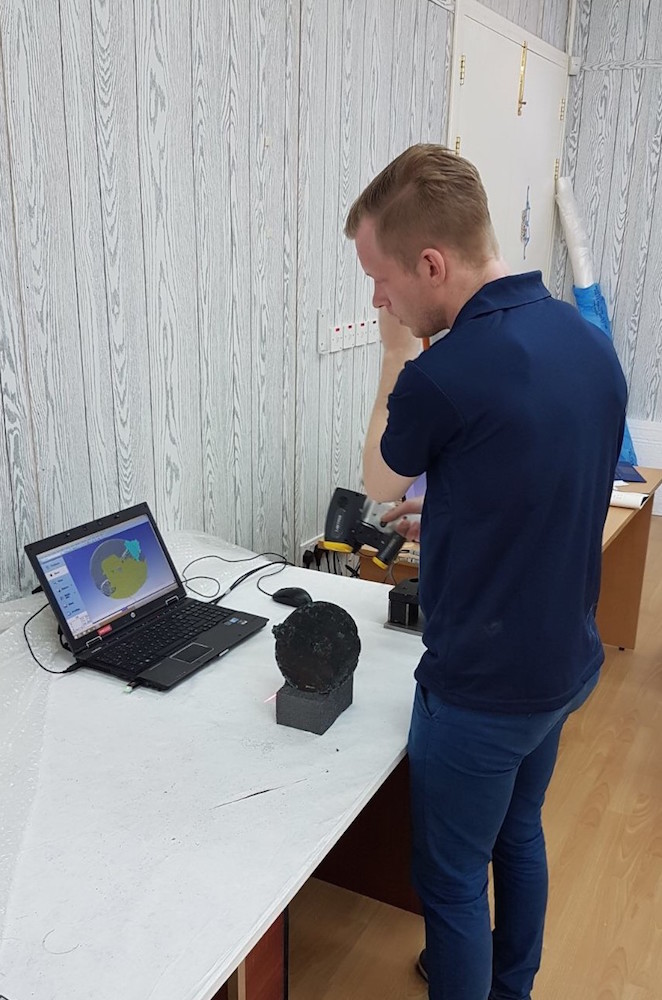

Divers found the artifact in 2014, but were unsure exactly what it was at the time. Now, thanks to a 3D-imaging scanner, scientists were able to find etchings on the bronze disc that confirmed it was an astrolabe.

"It was fantastic to apply our 3D scanning technology to such an exciting project and help with the identification of such a rare and fascinating item," Mark Williams, a professorial fellow at the Warwick Manufacturing Group at the University of Warwick, in the United Kingdom, said in a statement. Williams and his team did the scan.

The marine astrolabe likely dates to between 1495 and 1500, and was aboard a ship known as the Esmeralda, which sank in 1503. The Esmeralda was part of a fleet led by Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama, the first known person to sail directly from Europe to India. [The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

In 2014, an expedition led by Blue Water Recoveries excavated the Esmeralda shipwreck and recovered the astrolabe. But because researchers couldn't discern any navigational markings on the almost 7-inch-diameter (17.5 centimeters) disc, they were cautious about labeling it without further evidence.

Now, the new scan reveals etchings around the edge of the disc, each separated by five degrees, Williams found. This detail proves it's an astrolabe, as these markings would have helped mariners measure the height of the sun above the horizon at noon — a strategy that helped them figure out their locationwhile at sea, Williams said.

The disc is also engraved with the Portuguese coat of arms and the personal emblem of Dom Manuel I, Portugal's king from 1495 to1521.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Usually we are working on engineering-related challenges, so to be able to take our expertise and transfer that to something totally different and so historically significant was a really interesting opportunity," Williams said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.